I’ll get right to the point. The King Lear I saw last weekend courtesy of NT Live is the most thoughtfully conceived, perceptively acted and richly achieved production of Shakespeare’s great tragedy I’ve ever seen. It stars Ian McKellen, and that in itself more than recommends it. But it’s far more than a star vehicle.

Part of the National Theatre’s live-capture series from British stages, it’s onscreen on Monday Nov. 12th at Amherst Cinema.

Part of the National Theatre’s live-capture series from British stages, it’s onscreen on Monday Nov. 12th at Amherst Cinema.

This one isn’t a National Theatre production but a West End transfer from the intimate Chichester Festival Theatre. Instead of sprawling across an expansive stage, it’s packed into a tight circumference and a walkway bisecting the stalls. As McKellen says in a pre-show video, the audience in the theater is close enough to see the whites of the actors’ eyes, and for those of us peering through the camera’s lens, close enough to watch a tear glisten.

Jonathan Munby’s production is semi-modern-dress – medal-decked military uniforms and camo fatigues mixing with the women’s sheath gowns – and it’s set in a semi-post-modern era. Shakespeare’s script imagines a pre-Christian Britain where the characters invoke the classical gods in moments of benediction, anger and torment. Here we seem to be in a post-Christian near-future where feudal fealty has re-emerged but is now tottering, where wars are waged with assault rifles and duels are fought with knives.

Interviews in the pre-show segment also suggest that we moderns might be struck by echoes of current events. The plot’s springboard, Britain split up by the irrational actions of a monarch fixated on the wrong priorities, did summon thoughts of Brexit, the “poor naked wretches” Lear encounters in the storm were unmistakably present-day homeless people, and when McKellen’s Lear spoke of “a scurvy politician” a titter of recognition ran through the cinema.

Interviews in the pre-show segment also suggest that we moderns might be struck by echoes of current events. The plot’s springboard, Britain split up by the irrational actions of a monarch fixated on the wrong priorities, did summon thoughts of Brexit, the “poor naked wretches” Lear encounters in the storm were unmistakably present-day homeless people, and when McKellen’s Lear spoke of “a scurvy politician” a titter of recognition ran through the cinema.

But this is no self-conscious “concept” production, using the text to make a contemporary point. It’s a brilliantly insightful, exquisitely detailed vision of the characters and their ruptured relationships, drawing them out in surprising ways that are true to the text. And that moment-to-moment attention to detail holds our own attention throughout the three-and-a-half-hour performance.

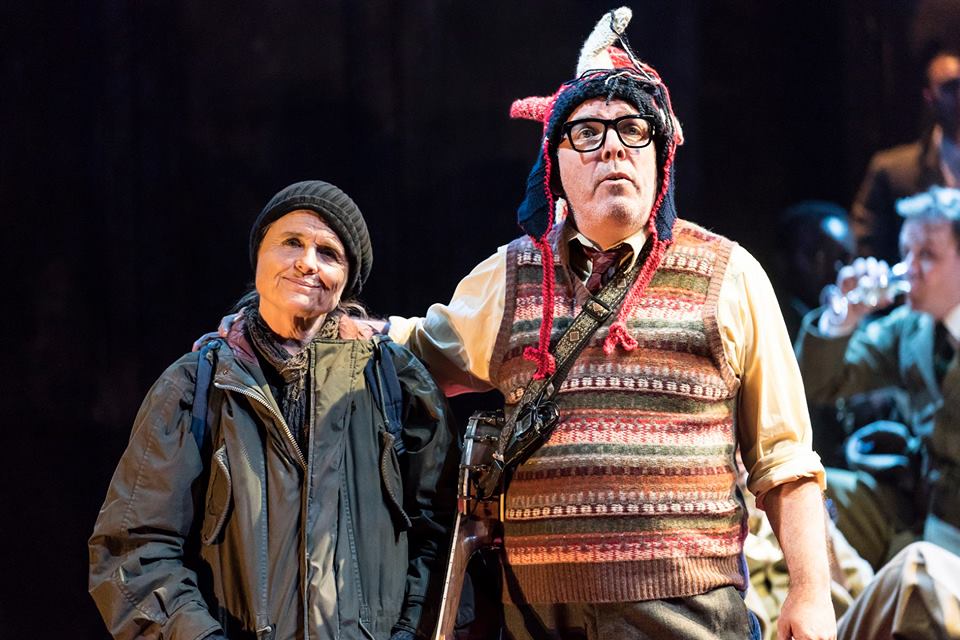

There’s some “color-blind” casting, now standard on British stages, and one piece of pointed cross-gender casting. The Earl of Kent becomes a Countess, with a no-nonsense Sinéad Cusack adding a woman’s wisdom to the king’s closest advisor and most straight-talking truth-teller (while Lloyd Hutchinson’s banjolele-strumming Fool speaks truth to power with jokes and ditties).

There’s some “color-blind” casting, now standard on British stages, and one piece of pointed cross-gender casting. The Earl of Kent becomes a Countess, with a no-nonsense Sinéad Cusack adding a woman’s wisdom to the king’s closest advisor and most straight-talking truth-teller (while Lloyd Hutchinson’s banjolele-strumming Fool speaks truth to power with jokes and ditties).

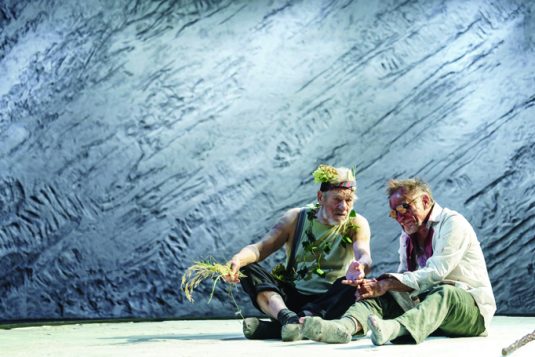

As the Earl of Gloucester, who loses his eyes in loyalty to the king, Danny Webb is not the usual crusty-but-sweet old fellow but a prickly, brittle lord, quick to anger and casually contemptuous of his bastard son Edmund. This in turn makes James Corrigan’s Edmund more than a pure villain jealous of his “legitimate” brother. When he fumes “Why bastard? Wherefore base?” you can see the hurt in his eyes.

As the Earl of Gloucester, who loses his eyes in loyalty to the king, Danny Webb is not the usual crusty-but-sweet old fellow but a prickly, brittle lord, quick to anger and casually contemptuous of his bastard son Edmund. This in turn makes James Corrigan’s Edmund more than a pure villain jealous of his “legitimate” brother. When he fumes “Why bastard? Wherefore base?” you can see the hurt in his eyes.

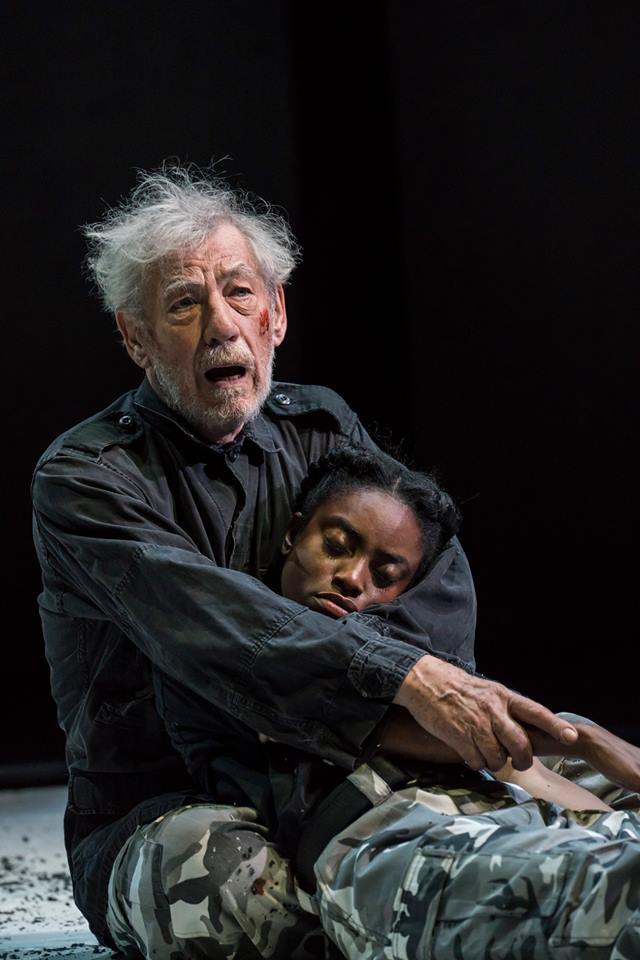

Anita-Joy Uwajeh gives artless young Cordelia, discarded by her father for her honesty, a muscular resolve. As Lear’s faithless scheming daughters, Claire Price makes a steely, Chanel-suited Goneril and Kirsty Bushell, in what is perhaps the production’s one overreach, makes Regan a spoiled narcissist, bratty, flirty and finally sadistic, in a bloodthirsty spasm enacted with orgasmic glee.

Anita-Joy Uwajeh gives artless young Cordelia, discarded by her father for her honesty, a muscular resolve. As Lear’s faithless scheming daughters, Claire Price makes a steely, Chanel-suited Goneril and Kirsty Bushell, in what is perhaps the production’s one overreach, makes Regan a spoiled narcissist, bratty, flirty and finally sadistic, in a bloodthirsty spasm enacted with orgasmic glee.

McKellen’s performance in the title role is exemplary of all the acting here – clear, unforced, transparent and natural. Nearing 80, at the summit of a brilliant career (with a Sir in front of his name), he has both the actor’s experience and the king’s majesty to give us a Lear of infinite variety, by turns fearsome and poignant, brash and broken, self-centered and self-aware, deeply emotional without histrionics but letting the passion pour forth when he rages against the storm, “a man more sinned against than sinning.”

It’s also a thoroughly generous performance. He’s no center-stage star but a wholehearted collaborator, and his fellow actors, no less unstinting, more than repay it.

Photos by Johan Persson & Manuel Harlan – see gallery

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email StageStruck@crocker.com