“One of my first memories of discrimination was when I was 10 or so,” said Gloria Graves Holmes, one of two co-facilitators of the Bridge 4 Unity project. “When I was standing on a corner, getting ready to cross the street, a white man drove by me and screamed ‘Go back to Africa!’ I never saw him again, but that moment resonated.”

Gloria Graves Holmes, center, facilitates a discussion in South Carolina for Bridge 4 Unity. Photo courtesy Bridge 4 Unity

An echo of that moment occurred years later, when she and her family were moving into their dream home on the suburbs of Long Island. A white man drove past and shouted a racial slur.

“I was a full-time teacher, a masters-level student, a mother, and wife, building a dream home with my family, and the night we moved into our newly-built home, I hear, ‘Nigger go home.’”

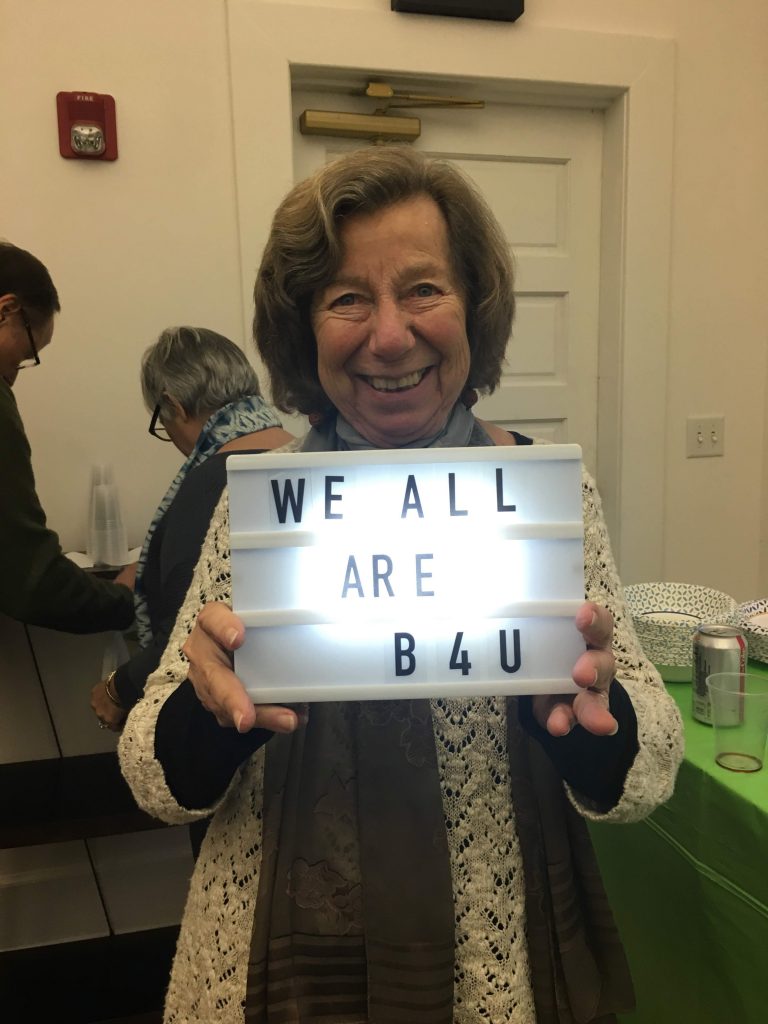

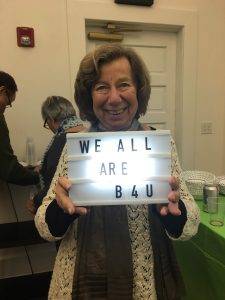

But for Graves Holmes, the topic of racism is not one to bury or shy away from, and that’s precisely the topic Bridge 4 Unity, a mixed-race group from western Massachusetts, rural Kentucky, and the Lowcountry of South Carolina, is hashing out in round-table, face-to-face dialogues.

Established among people in these three states, Bridge 4 Unity’s mission is to bring people together from different backgrounds to discuss racism, often providing people with perspectives they have seldom been exposed to. Starting with monthly meetings in their home states, the participants then traveled to a site in the South Carolina Lowcountry in January for a three-day intensive discussion on the topic of racism. The groups are continuing to meet regularly in their own states, and will have another combined meeting in Massachusetts in June.

Graves Holmes, a longtime educator at Quinnipiac University in Connecticut, now lives in South Carolina. She joined the project after connecting with Deborah Snow, one of the project’s organizers, at the Blue Heron restaurant in Sunderland, where she was invited to speak last year about a recent book she wrote.

Graves Holmes, along with Leverett resident and longtime peacebuilder Paula Green, both were tasked with facilitating discussions among the Bridge 4 Unity participants at their meeting in South Carolina.

“For me I want to get at the cause, and the cause is our miscomprehension of each other, our stereotypes toward each other,” Green said.

Green also helped lead the Hands Across the Hills project, a discussion effort between Leverett and Letcher County, Kentucky, where she facilitated dialogues about political differences.

“We had a surprisingly successful, profoundly challenging dialogue exchange on all the hot-button issues, and discovered we had a lot of common ground,” Green said of Hands Across the Hills.

But Green knew that tackling race was going to be a bigger challenge.

“The topic of race is a much more tender topic than politics,” said Green, who is white. “People are afraid of saying the wrong thing.”

Green founded the Karuna Center for Peacebuilding in Amherst and has worked for 30 years as a facilitator in places experiencing armed conflict — including Rwanda, Israel and Palestine, Kosovo, Bosnia, South Sudan, and South Africa.

Green said dialogue is a way to rehumanize people who have been dehumanized through conflict. With racism in America, there are 400 years of history that still divides people today.

At the January meeting in South Carolina of Bridge 4 Unity, Green and Graves Holmes provided prompts, carefully selected based on the level of trust and intimacy of the group, to get at questions such as “Do you think racism is getting better or worse?” and “What would you do or say if someone called you a racist?” The participants, 18 from Massachusetts, four from Kentucky, and about a dozen from South Carolina, sat in circles and discussed their answers.

Graves Holmes said she used her role as facilitator to do her best never to shut anyone down, but to get people talking about the bias that exists in the world. The conversations are uncomfortable, but necessary, she said.

Running up to the project, Green held monthly dialogues among the western Massachusetts participants starting in September. Graves Holmes met with people in South Carolina, as well.

In June, participants from Kentucky and from South Carolina will come to Massachusetts for the next phase of the dialogue project.

Large news agencies, including the New York Times and the BBC, have keyed into this project, and for both facilitators, despite the personal nature of the dialogues, they are happy for the attention. They hope this is an idea that will spread.

As a part of that outreach, Green and other Western Mass participants held an information session in Amherst on Feb. 24. About 150 people showed up.

“People all over are hungry for this,” Green said. “We know this is toxic and dangerous. We don’t want to be enemies.”

The Advocate spoke to several members of the group, mostly from Massachusetts but some in the other states, to hear their impressions of the experience.

A matter of survival

Amilcar Shabazz, 59, of Amherst is a professor in the W.E.B Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Seated in his office to speak about his participation in Bridge 4 Unity, he was surrounded by shelves of books on topics including civil rights history and African American thought. Shabazz, an African American man, said he was curious about the project, but also somewhat hesitant to fully commit to it.

“I feel as though among almost all of the folks of color there, there was a significant level of skepticism,” he said.

Shabazz said people of color in his generation, living in a society dominated by white people, have had to learn to understand white people as a matter of survival, whereas the opposite is not true.

“You come into a process like this and your life experience has you wondering, ‘What are these people here for? What do these people want?’” Shabazz said.

One thing that helped from the outset was the facilitators establishing ground rules, according to Shabazz. Among them were using I statements and avoiding personal attacks. Still, it was clear that this process was going to take participants out of their comfort zones.

“Here you are with people you don’t know, and you’re maybe having to wrestle with some things that ordinarily you wouldn’t spend your free time doing,” Shabazz said.

Deciding to commit to the monthly meetings, Shabazz began meeting with the other Western Mass participants in October. By December, he felt the quality of the discussions was getting better and that he was feeling more of a connection to the group. But the trip to South Carolina, which took place in January, he described as powerful, and it deepened his commitment to the process.

“I think what happened there is we really began to not just feel as though we were committing to a process of discussion, but that we were committing to a process of change — personal and social change,” he said.

Members of Bridge 4 Unity walking by a tree covered in moss in South Carolina. Photo courtesy Bridge 4 Unity

Among the books in Shabazz’s office is one about the Penn Center, the historical site on the South Carolina Beaufort Sea Islands where the dialogues took place. Shabazz confessed that, though he had it, he didn’t find it among his shelves, until he and the others returned home after the trip.

For Shabazz and the others, this site — a retreat space used in the 1960s by people in the Civil Rights Movement, including Dr. Martin Luther King — provided an appropriate place to have the discussions. He said that walking by old oak trees covered with Spanish moss hanging from them, he reflected on the generations of Africans who experienced slavery on the site, followed by a war and then white people leaving the islands. Later, residents of the island lived as free people profiting from their own work, but also experienced backlash and attacks. “Yet people go on with their lives trying to have some hope as they raise children and produce new generations into this world. And to think in that moment that damn, it is 2019 and we’re still talking about racism; we’re still talking about white supremacy; we’re still talking about the inhumanity of human beings being inhuman to each other.”

For him, the wave of African American deaths that has sparked the Black Lives Movement, and the sense that racist acts are on the rise in America weighs heavy. But the dialogues helped buoy his optimism.

“The process has rekindled a kind of hope that for me had begun to fade,” he said. “The sense I had was one of really a deep lack of hope in the country even in the up and coming generations.”

What the dialogues showed him was that on a small scale, people can come together. He imagined what larger-scale success for the project might look like.

“I’m interested in seeing people from oppressed communities just being unapologetically fierce about taking our seat at the table where the decisions are made on everything,” Shabazz said. “Along with that, I want to see white people become unapologetically fierce about demanding that those of us from communities that were once oppressed are at the table.”

As an example, Shabazz said presidential hopefuls like Bernie Sanders and Joe Biden should look at the other candidates in the race, candidates of color, and decide who among them to put their support behind rather than running themselves.

An indigenous perspective

Kara Nye of Holyoke, a band teacher at Amherst Middle School and Amherst High School, stands out from the group in a few ways. At 30, she is the youngest participant and, as a member of the Odawa people, a tribe of the Anishinaabe, she is also one of only two indigenous people in Bridge 4 Unity — the only ones who are neither black nor white.

Nye said that often discussions of racism focus only on black and white, but that different issues emerge when representatives of a more full spectrum of people are present.

“When you’re talking black and white, you’re talking the history of slavery; when you’re talking about natives, you’re talking the history of genocide,” she said.

People are largely unaware of the existence of indigenous people, especially in New England, Nye said. They often think all native people are dead or off in the West somewhere living on reservations, she said. They don’t realize that there are indigenous lands and people in Massachusetts and urban Native Americans from all over the place.

As a teacher, Nye tries to create spaces where students can share experiences with her, including about racism.

“My goal is not to impose my own feelings on them. They have plenty of their own experience with race. I want to create a safe space for those discussions early on,” she said.

For those who look to the young people to solve racism, Nye said that younger people do not necessarily have a more anti-racist view.

“Racism is adaptable. It does not look the same generation to generation, but it does not disappear and that’s a common misconception people have,” Nye said. Even with vast improvements related to Civil Rights in the political sphere, racism is nuanced and continues to exist in people’s personal lives.

White people can be slow to see this, or even willfully blind to it, which can make discussions of race more fatiguing for people of color, who she said are often expected to explain racism to white people.

“People of color live the experience of racism 24/7 from birth; white people are introduced to the experience of racism and people not like themselves much later in life,” Nye said.

During the Bridge 4 Unity discussions, however, Nye said she felt that she and other people of color were well cared for during a grueling three-day period of intense discussion.

Subtle, indirect, and even unintentional racism exists in a multitude of forms, and a term many use to describe those moments is “microaggressions.” Bridge 4 Unity members worked hard to account for these acts by encouraging each other to say “ouch” or “oops” — the former to communicate when something said was hurtful to them, the latter when they said something unintentionally hurtful.

The need for such a system became starkly obvious during one session the group had in South Carolina that was open to the public. Among the group were people who had not been through the dialog process, and one visitor, a white woman, upon hearing another member of the group speak said that she was very well-spoken for an African American.

A silence fell over the group. Those who had been part of the dialogues felt the implicit racism in the woman’s remark, that it was surprising that an African American woman would be well-spoken.

But rather than the onus falling on one of the group members of color, a white participant spoke up, explaining in a polite way that the woman’s words were hurtful.

This was a meaningful moment to many interviewed.

For Nye, it showed the difference between how the group responded as opposed to what usually happens. This group, having spoken about racism for three days, was primed to respond and combat the incident immediately.

“There was a moment in which a white person spoke up identifying something as an example of racism that had happened in a way that created space for the people of color involved and in the room to be honest about its impact, but didn’t place the burden of educating on the people of color,” Nye said.

The white woman asked if she had hurt the other woman’s feelings, and the African American woman said that yes, she did.

Even though people of different races live in Western Mass, getting out of the region was an important ingredient for the conversations, Nye said.

“The Valley is so academic and we need to be able to talk to everyone,” Nye said. “Class diversity and education diversity — that’s not what this is about, but it’s completely interwoven.”

For Nye, creating connections among people, as those that were created through the Bridge 4 Unity dialogue process, is important work, and is a way to make unexpected friends. She said she is looking forward to seeing all of them again when they come up to visit Massachusetts in June.

“White people who voted for Trump, I can’t wait to see them. It is a fascinating situation.”

Living with guilt

Gwen Johnson, 60, is one of four people who participated in the project from Kentucky. She is white and voted for Donald Trump for president in 2016. She also is a board member at the Hemphill Center, a community gathering space featuring music, food, craft traditions from the region. The center has programing that helps people recovering from addiction and long-term incarceration.

Gwen Johnson, left, leads the group in song during a meeting of Bridge 4 Unity. Photo courtesy of Bridge 4 Unity

“That’s my heart work,” Johnson said. “I’m the overseer of those efforts.”

This wasn’t Johnson’s first foray into such discussions. In 2017 she made a trip to Massachusetts as a member of Hands Across the Hills, which led to her involvement in Bridge 4 Unity.

Johnson was at first hesitant to get involved with the Hands Across the Hills project to discuss political differences in the country. In the past her region has been portrayed as ignorant, poverty-stricken hillbillies, she said, and she didn’t want to participate in something that furthered that stereotype.

In the end, she agreed so that she could speak for herself rather than other people speaking for her.

“My greatest fear when we went to Massachusetts was that people were angry at us for voting for Trump,” she said. “We had a reason, but I didn’t expect them to understand those reasons.”

What impressed her was that people did understand — when she brought up her concerns about coal-mining jobs that supported her family, and about the difficulties she and her neighbors experience in taking care of their families and elders.

“They understood perfectly when I said that I could not vote for Hillary because a vote for her I felt was to betray my people,” she said.

A burial site at the McLeod Plantation, where members went on a tour during their trip. Photo courtesy Bridge 4 Unity

After that experience, Johnson felt comfortable participating in Bridge 4 Unity, which she saw as an extension of Hands Across the Hills, but with the much weightier topic of race.

“These dialogues cut through all the bullshit of the middleman and cut right to the chase,” she said. “When you talk about your feelings, who can naysay your feelings? They are yours.”

The dialogues gave her a chance to talk about guilt she still felt over an incident from when she was a first-year student in high school in 1972. She stood by and watched as a group of people beat up an African American student, a senior. She didn’t step forward to the young woman’s defense, even though she knew it was wrong. The mining union her family belonged to was never segregated, and her father had African American friends upon whom his life depended in the coal mine.

“I think of how hurtful that was to her, but it was also hurtful to me, because I never should have just stood by,” she said. “And I lived with that shame for all those years.”

There is power in regular people speaking with each other, as those who are wealthy or in power often seek to divide, she said.

“I think that if some of these conversations began to happen all over the nation, I think some of the social unrest would be laid to rest,” she said.

Connecting through food

One of the people Johnson related with most in the project was Neftali Duran, 40, of Holyoke, the other Bridge 4 Unity member in addition to Nye who identifies as indigenous.

Neftali Duran, center with Gwen Johnson and Beaufort, South Carolina, Mayor Billy Keyserling. Photo courtesy Bridge 4 Unity

“The first connection we had was talking about food,” Duran said. “We would never have met in other circumstances, and by the end of the time together, we had had a conversation that went on for a few days about food scarcity, cultural appropriation, and the fact that in all of our communities, one of the similarities we have as we care deeply about food.”

Duran grew up in the southern part of the Oaxaca region of Mexico, came to the United States as a migrant worker, and has been working in kitchens ever since.

Duran, Johnson, and Sonja Griffin Evans, an African American participant from South Carolina, videotaped a conversation they had in which the three spoke about different aspects of what has been described as “poor people’s food.” The video is available on the Bridge 4 Unity Facebook page.

“When you’re in situations where you have to survive, that’s where your creativity kicks in,” Griffin Evans says in the video as Duran and Johnson nod along.

Food and its cost can be a way of dividing the haves from the have-nots — Johnson likened some of the profit-making from high-end restaurants selling “poor people’s food” for inflated prices as something “akin to theft of intellectual property.”

Sonja Griffin Evans, Gwen Johnson, and Neftali Duran speak about the topic of food as Kara Nye videotapes. Photo courtesy Bridge 4 Unity

But food is also a powerful force for bringing people together. At each of the Bridge 4 Unity events, the opportunity to eat food together helped make connections.

Duran said his participation in the Bridge 4 Unity project was a way to push himself out of his comfort zone to discuss important topics of race and prejudice.

“As a man of color, people are always going to have preconceived ideas of who I am,” Duran said. “I push myself to not do the same to other people.”

Often people will automatically want to talk to him in Spanish, assume he doesn’t speak English, or speak very slowly to him. These actions don’t fall under the category of extreme racism, but of microaggressions.

“It’s something that lives on a lower spectrum of racism,” he said. “Microaggressions usually come out of ignorance and not understanding what racism is.”

For Duran, the Bridge 4 Unity project was the first time he had been as far south as South Carolina, but he said racism exists in many forms and in many places, including in progressive western Massachusetts.

“It exists but people may not necessarily want to deal with it and acknowledge it at home,” he said.

Duran has a 19-year-old son, and is interested in watching his son grow up in a different generation than his. As an example of the differences, he said young people are used to using different pronouns that make space for gender nonbinary people, like the singular “they.”

“Honestly, raising a son, a young boy, in this day and age, it gives me hope,” Duran said. “I know a lot of the vices that existed in my generation are changing and I think that we need to pass the mic to the youngsters to lead this movement.”

Rewriting the story

Rose Sackey-Milligan of the Indian Orchard neighborhood of Springfield grew up in the Caribbean and moved to the Valley in 1984.

While she said racism does exist on the islands, Sackey-Milligan, an African American woman in her mid-60s, said coming to the States brought racism front and center into her life.

“It is the air I breathe and the water I swim in,” she said.

In the 1980s, when Sackey-Milligan was working as an activist on anti-racist efforts, conversations that would start about white supremacy would progress into white participants getting defensive or so guilt-ridden and filled with shame that they could not engage in a conversation.

That made her hesitant to join Bridge 4 Unity, though she did commit to it.

“I have mixed feelings about the group,” Sackey-Milligan said. “I think, for certain, people are honest. I believe white liberalism still prevails, but I also feel that there has been some shift since 30 years ago in people’s understanding of how racism works.”

She said the change is promising and it reminds her that change is slow. White people in the Bridge 4 Unity group were able to own their guilt, get beyond their shame, and take responsibility for their part of working toward a solution to the problem.

“For me I think trust is not fully established yet,” Sackey-Milligan said. “This will happen over time, but there’s enough there to work with.”

In addition to the discussions about race, Sackey-Milligan said the relationships are being formed in an honest way, and that is a way for transformation to happen.

That is important, because society at large tells a harmful story about race — with minority populations and white people internalizing negative ideas about subordination and dominance — and the way to get past it is to rewrite that story through personal interactions and experience, she said.

“When you meet people and you talk to people, you get a better sense of who they really are and you see that the story you believed about them as a group is not really reflected in what’s before you,” she said.

It is more meaningful than having institutions focus on surface-level inclusion and diversity efforts that may bring more people of color into the organization, but does nothing to alter the power structure that keeps white people in a dominant position.

Her hope is that Bridge 4 Unity inspires other discussion groups to do the same thing in starting meaningful dialogues and begin a process of deep relationship building — especially among young people.

“When I see millions of white folks marching in Washington and they are enraged and in protest of white supremacy, and people are serious, not just because it is fashionable, that to me is an indication that we are in a different place,” she said.

Reinvigorating activism

Deborah Snow, 68, of Montague Center was an activist in her youth. The 2016 election that saw Donald Trump become president inspired her to become active again. Among the forefront issues she wanted to tackle was racism, and through that she became one of the principal organizers of Bridge 4 Unity.

“First and foremost, I’m pretty sick of the racism in our country,” said Snow, who is white. “It doesn’t represent who I am and I want to do all I can to do to change that. My belief is that you can’t just not be a racist, you have to be anti-racist. You have to work every day to change people from the inside.”

Snow said she believes more people of all races will begin working to combat racism that has existed long before the inception of the country.

Being angry at the problem is not enough. And part of getting beyond the anger and having good dialogues is having skilled facilitators like Paula Green and Gloria Graves Holmes, who presided over the discussions.

“I joke with people when I talk in these dialogues that I was born angry and became really angry at society and the oppression that I felt as a young child, just being female, and then in my life as a lesbian,” she said. “But anger didn’t work for me. I need to transform the anger so I can have action and not reaction.”

She said she was angry for a long time at her brother, who defended a policy followed by the insurance company he worked for: not selling to people based on their sexuality. It was deeply hurtful, but Snow said eventually they began communicating about other things and he reached out to her once in need. Later, after more discussions between them, he became a firm believer in gay marriage.

“Instead of pushing him away, I was able to bring him in,” she said.

Racism, she said, is hurtful to all. Minority populations are harmed through discrimination, and white populations, too, are connected with the shame of a history including enslavement and colonialism, which she described as the “original sin of these United States.”

“I understand that my being white gave me a lot of privilege, but I pay a price for that privilege, and that is a loss of humanity,” she said.

Snow pointed out that the idea of Bridge 4 Unity was to connect with people in other states, but that racist divides exist in the Valley, too. What many call the “tofu curtain” — separating the Springfield and Holyoke areas from Northampton, Amherst and further north — she believes has to do with racism.

“We’ve talked about that in the group, that we have our own north-south thing happening,” Snow said.

For Snow, care was taken to find participants in the project from Springfield and Holyoke, but transcending that divide may mean having events in those areas similar to the one that was held at the Amherst church.

The importance of history

Gina Miller, a white woman originally from New York, and Galen Miller, a member of the Gullah people — African Americans who live in the Lowcountry region of South Carolina and Georgia — have been married for 17 years. Both 48 years old, they live in Hilton Head in the Beaufort Sea Islands of South Carolina with their two children, a 15-year-old girl and a 12-year-old boy.

Both were eager to be involved when they heard that visitors from Massachusetts were going to be coming to engage in dialog about race.

“We’re an interracial couple,” Gina Miller said. “I have been enriched by that experience, and have also had my eyes open to different experiences of people who grew up differently than me.”

Galen Miller, a member of the local Martin Luther King Jr. chapter, said he has had little direct experience with racism in his community, but that he knows his family’s history of being enslaved and he is always looking for ways to follow in Dr. King’s footsteps to build a better world.

“By far my biggest passion is to get involved with kids and making sure they are understanding what Dr. King did for them,” Galen Miller said.

For the Millers, who live roughly an hour’s drive from the Penn Center, it was striking how much history was infused into the dialogues — including the history of enslavement that took place on the very soil where the talks were happening. Gina Miller said it was a shame more history isn’t incorporated into the school systems, particularly their local schools.

“History that is shared in the schools is celebratory — this invention or this machine was invented by a black man,” she said. “While there is a place for that, we all have a responsibility to understand the cruel history that has cast a shadow to this day.”

Galen Miller recounted his own family’s history, with grandparents who were sharecroppers on the island and growing up with horses, cows, and vegetables of all kinds. At the same time, his mother went to a segregated school.

In many ways, forms of segregation and separation continue. Both Millers said they had never spoken to anyone from Kentucky before, and had little knowledge of people who worked in the coal industry. Gina Miller had never spent time with indigenous people before.

“We formed deep friendships in three days, and I say that with all sincerity,” Gina Miller said.

Part of the reason for this, in her mind, was that people were coming into the conversations from a place of pain, struggling with the state of the world.

“I’m a very empathetic person and being married to Galen and seeing first hand the different experience of a black child or a poor child compared to the experience I had growing up,” she said. “In this community — it’s a wonderful community but there is a big divide between extreme wealth and extreme poverty. Every experience I have or we have as a family makes me reflect on the lack of opportunities that other people have because of the nature of the color of their skin or socioeconomic status.”

In Hilton Head, known as a resort community, there is a lot of poverty invisible to most people. In some cases African American families who have lived on pieces of land for generations have been forced off due to a lack of legal documents like property titles and wills — leading to auctions where others can scoop up the property for pennies on the dollar as those who live there beg not to have the property taken away.

“It’s hard not to have your heart broken,” Gina Miller said.

‘We all suffer from racism’

For Tim Bullock, 70, of Leverett, Bridge 4 Unity is not the first time he traveled a great distance to discuss the racial divide. In 1998, Bullock participated in a year-long journey tracing the trans-Atlantic slave trade beginning in Leverett and ending in Cape Town, South Africa, called the Interfaith Pilgrimage of the Middle Passage.

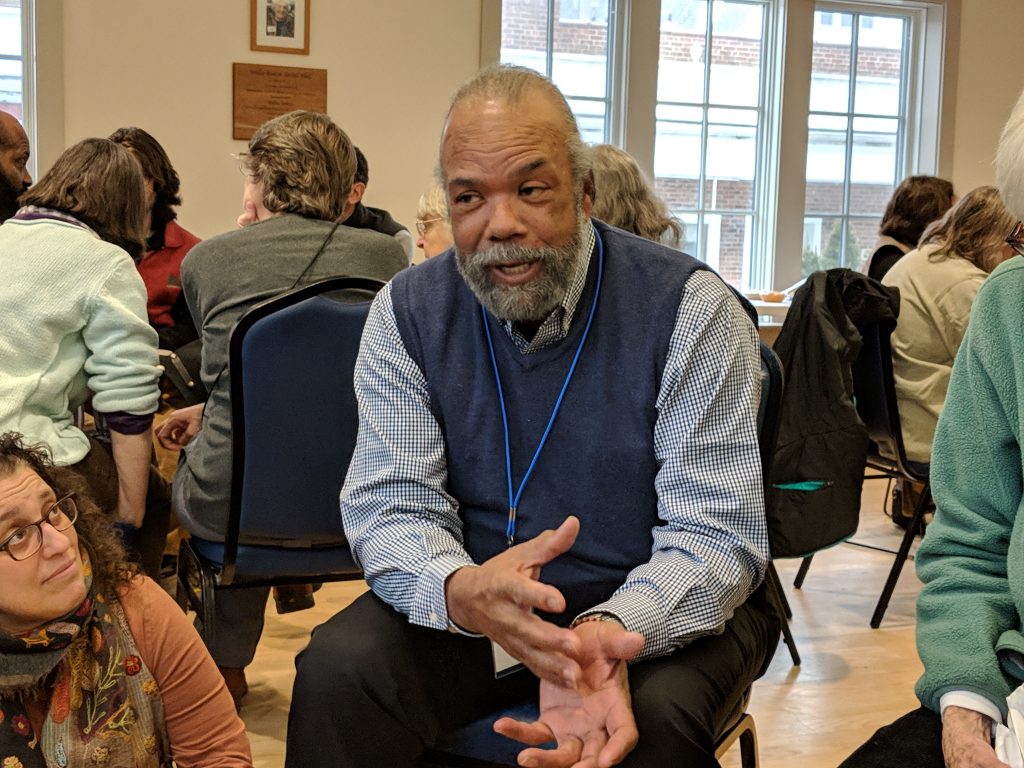

Tim Bullock speaks to people at the Bridge 4 Unity event in Amherst in February. Dave Eisenstadter photo

“We walked for five months along the East Coast, ending up in New Orleans, and then on to Key West, Florida, through the Caribbean. A few of us went down to Brazil and the rest went to West Africa,” he said.

Bullock, an African American, is a part of the New England Peace Pagoda community in Leverett and organizes their yearly walks for peace.

While Bullock was not initially sure he would be able to commit to the monthly meetings in Bridge 4 Unity, he quickly became convinced.

“Each one of those meetings was so fulfilling that I knew that I had to be involved,” Bullock said. “It was like finally finding a group of people who were unafraid to look at issues that had affected me all my life and have them understand it in the way I understood it.”

When Bullock was traveling and discussing racism 20 years ago, many people wondered why it was necessary to talk about, given the strides made by Dr. King and many others. And then others believed that racism had somehow gone away because Barack Obama was elected president.

But that has changed, he said.

“Today with Black Lives Matter, racism isn’t as shrouded as it used to be,” Bullock said. “More and more we’re coming to realize the effects of racism in our society and its history in our country.”

Having a mixed group to talk about the issues of racism gets beyond conversations Bullock said he has regularly with his family, where racism does come up.

“When you are talking among family or people in your own situation, a lot of times it is complaining and you don’t really get to see the other side’s story,” he said. “But when you’re sitting across from people who are different from you and hearing stories, it gives you a whole different perspective.”

Bullock continued: “I also have come to understand that we all suffer from racism. Whites also have to understand the negative impact of racism on their lives.”

When the South Carolina and Kentucky residents come to visit Massachusetts in June, Bullock hopes to give them a good understanding of New Englanders. He hopes that the crowd at the public event in February in Amherst — about 150 people — doubles in size when Bridge 4 Unity holds a public event with the visitors.

He also looks forward to the idea of dialogue spreading.

“I imagine each one of us, the 18 people in Massachusetts and the people in South Carolina and the people in Kentucky, starting our own little groups, and each one of us is just as successful in attracting people who want to be a part of this conversation,” Bullock said. “We have to go out and share this as broadly as we can. Success would be this dialogue for peace happening all over the state and all over the country and all over the world.”

For more information on Bridge 4 Unity, visit www.handsacrossthehills.org/bridge-4-unity.

Dave Eisenstadter can be reached at deisen@valleyadvocate.com.