Greetings from Toronto, where it’s still winter, the wind whipping in from Lake Ontario is keen and bracing, and so is the theater.

I’ve seen two plays here, a one-man show and an eight-woman show, both of them the work of bi-cultural authors, performed in key venues of the city’s vigorous alternative theater scene. Both plays revolve around questions of identity and belonging, race and culture, and both in their own ways involve … beauty pageants.

School Girls is a co-production of Nightwood Theatre and Obsidian Theatre Company, dedicated respectively to feminist themes and “the Black voice,” and staged in a gay-focused theater, Buddies in Bad Times — a good illustration of Toronto’s tight-knit performance community. It’s by Ghanaian-American playwright Jocelyn Bioh, borrowing from her mother’s experience in a private girls’ boarding school in Ghana and produced here by an all-woman artistic team.

The subtitle, “The African Mean Girls Play,” intentionally recalls the 2004 teen flick Mean Girls, with a similar plot arc involving jealousies and conflicts within a high school clique lorded over by a pretty, popular, peremptory Queen Bee. In this elite Ghanaian school, the ruling monarch is Paulina, who has her sights set on the Miss Ghana of 1986 beauty crown.

Her coterie, who gather to giggle and gossip in the school cafeteria — a gauntlet of long tables and benches flanked on both sides by the audience — includes Ama, who is gradually getting tired of Paulina’s preening arrogance (any reflection on our own King Bee may or may not be deliberate), the loyal Mercy and Gifty, an inseparable pair who speak and move practically in unison, and timid, pliable Nana.

All the girls are in a frenzy of anticipation, awaiting the arrival of a glamorous recruiter for the pageant, herself a queen-bee alumna of the school and a former Miss Ghana. Paulina assumes she’ll be chosen to compete, until the sudden appearance of a new student, mixed-race Ericka, upsets her expectations.

All the girls are in a frenzy of anticipation, awaiting the arrival of a glamorous recruiter for the pageant, herself a queen-bee alumna of the school and a former Miss Ghana. Paulina assumes she’ll be chosen to compete, until the sudden appearance of a new student, mixed-race Ericka, upsets her expectations.

“Wow! You are blessed,” the recruiter exclaims as she admires Ericka’s fair complexion, adding with a glance to dark Paulina, “The judges are fond of girls who have a more, ah, universal and commercial look — girls who fall on the other end of the African skin spectrum.”

The play opens with Paulina fat-shaming chubby Nana, whom she later bullies into committing a theft in an effort to undermine the new girl. But even more than adolescent fascism, Bioh’s satire skewers shadeism, illustrated not only by the recruiter’s take-no-prisoners quest for a beauty queen to follow in her own narcissistic footsteps, but by the girls’ own fascination with Ericka’s pale skin and smooth hair.

The cast, directed with boisterous energy by Nina Lee Aquino, is terrific, notably Natasha Mumba as Paulina, slowly brought down from sovereignty to submission; Melissa Eve Langdon as Ericka, slowly taking on the inevitable role; Allison Edwards-Crewe as the vainglorious recruiter; and Akosua Amo-Adem as the school’s starchy headmistress, torn between outrage and self-interest.

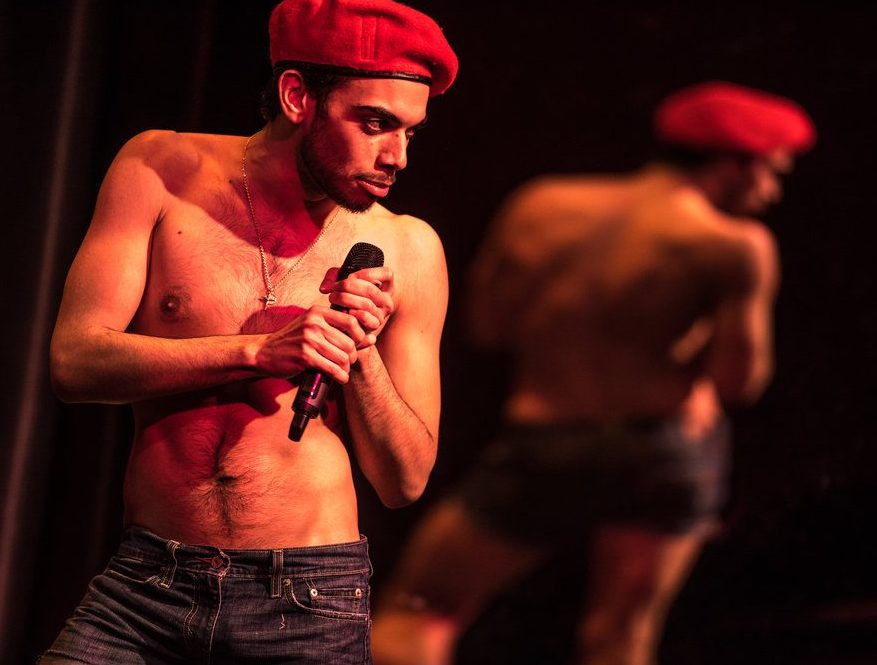

The beauty pageant highlighted in Chicho is one detail in an eclectic canvas painted by the chameleon writer/performer Augusto Bitter. The wide-ranging tour de force, snappily staged by Claren Grosz, is a co-pro between Theatre Passe Muraille (“Theater Beyond Walls”) and the upstart collective Pencil Kit Productions. Bitter’s title character (not-at-all-loosely based on himself) is “an ashamed queer Catholic man-boy from Venezuela,” and much of the show is devoted to confessions, anecdotes and send-ups around his origins and sexuality.

It’s also, of necessity, about the disaster that is today’s Venezuela. “Venezuela is known for two things,” he says — “beautiful beaches and beautiful women,” the latter distinction fueled by the country’s “rapacious beauty industry.” Right now, of course, the nation is known for the world’s highest inflation rate (currently 2.5 million percent), a desperate political crisis, a starving population, and a belligerent northern neighbor eyeing its oil reserves.

It’s also, of necessity, about the disaster that is today’s Venezuela. “Venezuela is known for two things,” he says — “beautiful beaches and beautiful women,” the latter distinction fueled by the country’s “rapacious beauty industry.” Right now, of course, the nation is known for the world’s highest inflation rate (currently 2.5 million percent), a desperate political crisis, a starving population, and a belligerent northern neighbor eyeing its oil reserves.

Similar contrasts run through the piece, as school-uniformed Chicho frequently stripteases into his near-naked alter ego, Chichi. Shame and anxiety alternate with shameless swagger, sexual tension wars with cultural temperament and immigrant alienation with ancestral roots, and Spanish mixes freely with English, often in the same sentence.

Bitter is a beguiling, thrillingly versatile presence, bouncing from campy to chilling, now bounding into the audience like a hyperactive game-show host to pop current-events questions, now detailing his family’s flight from Venezuela when he was ten (he has few good words for Chavez and none for Maduro).

Bitter is a beguiling, thrillingly versatile presence, bouncing from campy to chilling, now bounding into the audience like a hyperactive game-show host to pop current-events questions, now detailing his family’s flight from Venezuela when he was ten (he has few good words for Chavez and none for Maduro).

There’s a large full-length mirror that, like his body, is repeatedly uncovered and re-draped (by a bedsheet), a series of gay-themed puns (dick-tatorship, home-ophobia, the Queer-ibbean) and a talking avocado. This high-energy grab bag of moods and styles is powered by Bitter’s balletic physique and mobile face, split by a mile-wide grin that can suddenly freeze into a grimace — an apt representation of the man’s mixed feelings for his home country and his divided self.

School Girls photos by Cesar Ghisilieri

Chicho photos by Dalia Katz

The Stagestruck archive is at valleyadvocate.com/author/chris-rohmann

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email Stagestruck@crocker.com