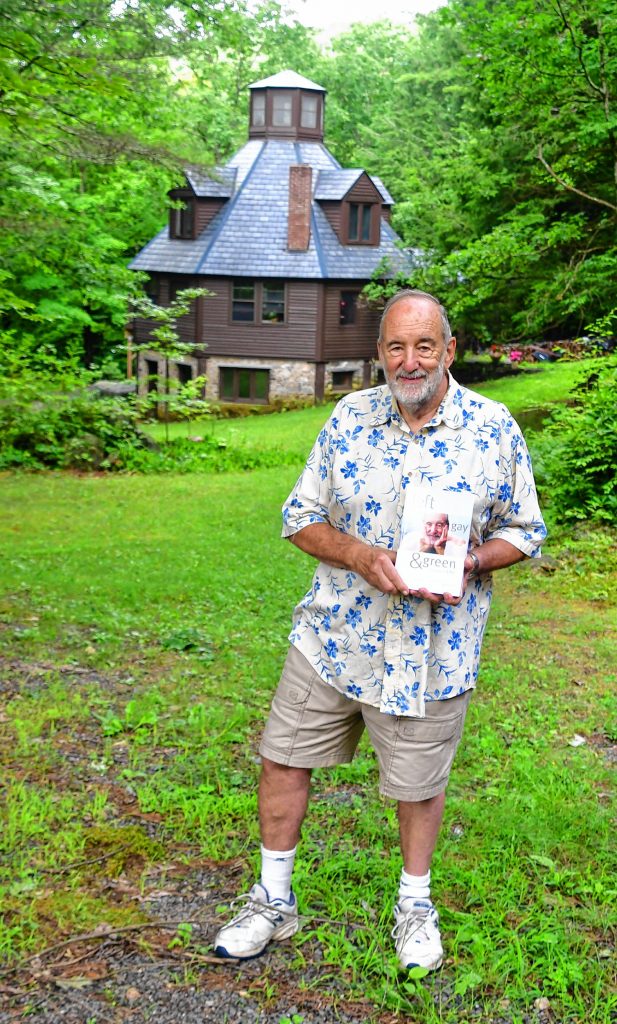

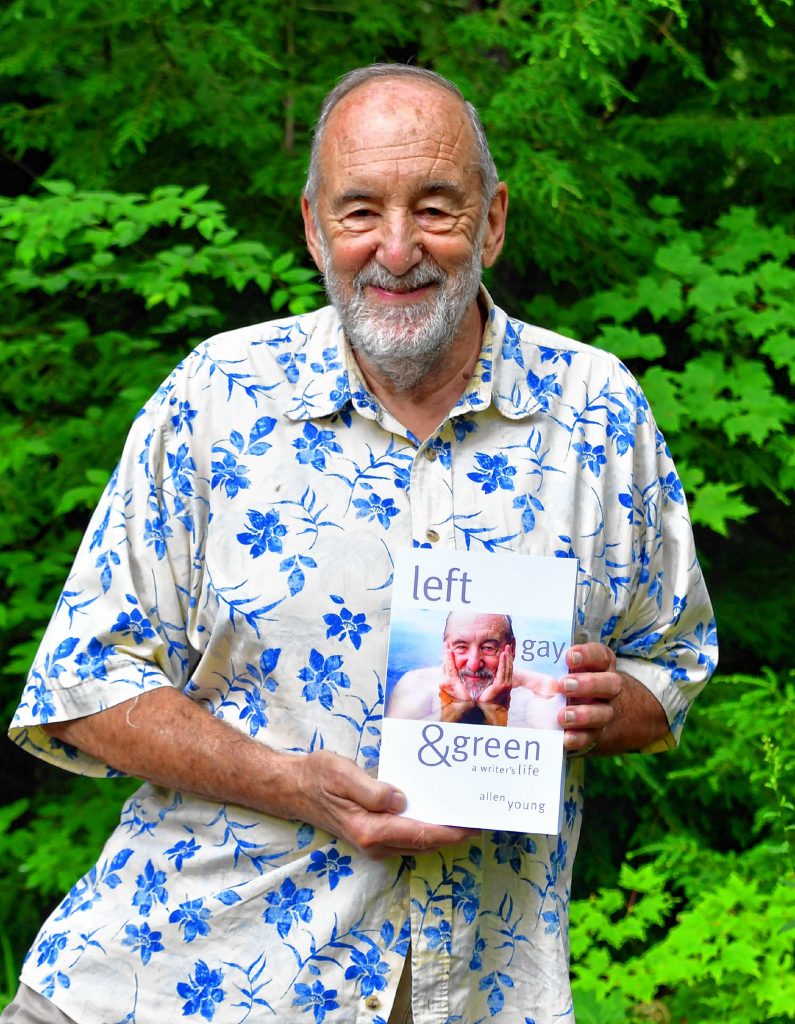

Born a red diaper baby in, of all places, Liberty, N.Y., and raised on a hardscrabble poultry farm owned by his American Communist parents, Royalston resident Allen Young’s life as it’s portrayed in his new autobiography, Left, Gay & Green: A Writer’s Life, has taken many paths and undergone personal transformations. But his core birthright leftist leanings have always followed him; hence, the “left” in the book’s title.

I don’t know if this is how Young, a nationally-known author, journalist, and columnist for the Athol Daily News, wants to be remembered, but it’s a part of the book that leapt out at me as quintessentially Young, even though he is so much more, which you’ll learn when you read the book. In a few successive sections of the book, he depicts his life from 1967 to 1971 as “the most intense period of my life.” Who among us of a certain age couldn’t say that? But for Young, now 77, it was tenfold.

By 1967, he had received an undergraduate degree from Columbia University, a master’s degree in Latin American studies from Stanford University, a master’s from Columbia University School of Journalism, and had studied and traveled under a Fulbright Scholarship (1964) in Chile, Brazil and throughout Latin America, where he filed freelance stories for the New York Times and the Christian Science Monitor, all the while having affairs and sexual encounters with women and men as part of coming to grips with being bisexual — and likely homosexual — a journey that had started in his early teens.

In the summer of 1967, Young was hired as a reporter for the Washington Post, and subsequently quit within a few months to write for the burgeoning leftist press in the United States, more commonly known as the Underground Press, and specifically for the Liberation News Service, an “Associated Press” of the Left.

Although he doesn’t explain precisely how, at some point in the 1970s, Young gained access to a CIA file through a Freedom of Information Act request. In 1976, that CIA report, which had been partially redacted, described Young: “[redacted name] was noted eating lunch with the infamous homosexual and Liberation News Service writer, Allen Young.”

The italic emphasis is mine. Therein, lays Allen Young. If he ever learned who [redacted name] was, he’s not giving it up in this book. In the interest of full disclosure, I’ve known Young personally for many years, and consider him a friend and colleague. His autobiography is part intimate and revealing tell-all of his personal journey and that of people he met along the way, both famous and not famous, and part extraordinary history lesson of the various movements of the ‘60s and ‘70s from someone who was experiencing and chronicling it all.

Whether it’s the anti-Vietnam War movement, the civil rights movement, the gay liberation movement, the environmental and no-nukes movement, and ultimately, the Back-to-Land movement of the ‘70s, which brought him to western Massachusetts along with, briefly, the Liberation News Service, Young recounts in accessible detail his participation and that of his friends in all of those history-making, societal transformations. He can be forgiven for name-dropping many of the noteworthy and sometimes notorious people of those decades because his interactions with them were real as part of his early journalism career, whether it’s Abbie Hoffman who once forged a round-trip airplane ticket from New York to Buenos Aires for him, or his job interview with then Washington Post managing editor Ben Bradlee, who inquired pointedly whether Young was “one of those leftists,” or his overnight ride on the Clearwater with Pete Seeger, or his time spent with Fidel Castro’s revolutionary Venceremos Brigade.

Left, Gay & Green: A Writer’s Life is a book for anyone, Baby Boomer to millennial, who wants to better understand the many millions among us that came of age amid the turbulence and change of those decades who were not only trying to make change, but make a life. It can provide both context and instruction for navigating while resisting the current period of resurgent anti-Semitism, misogyny, homophobia and racism we find ourselves in now.

Young writes with the clarity of a seasoned journalist, if not with the organization. The book, which is packed with pictures from back in the day up to the present, can be read in short takes as it’s a series of sometimes one to four paragraphs succinctly detailing a period in 20th century history that captured his mind, body, and pen or typewriter. Other passages are longer and filled with titillating particulars and unique reflections and opinions of the author. Still, I found the “chronology” of the book to be a bit disjointed. He also writes with the insight of someone who is accustomed to examining his life and its purpose and how he might better exist in it, none as poignant and honest as his journey toward accepting himself as a gay man or losing so many friends to AIDS.

The parts of the book that interested me most — and will interest many local readers — were the parts where Young decides, along with many other people of his generation, gay and straight, to craft our lives here in western Massachusetts, specifically Franklin County and the North Quabbin region. Those people included me, my husband and our young son when we moved to Warwick in 1974. I knew, and know, many of the fine people Young mentions as friends and co-conspirators. It’s a testimony to all who live here, especially the people here long before we came, that a group of intelligent, quirky, sincere, hardworking men who happened to be gay were accepted as part of the community.

As Butterworth Farm, the gay community established by Young and his friends in Royalston, was a gem of an idea born a coast away in San Francisco, Calif., he writes, “I was really quite alone, 31 years old, and with only the vaguest notion of what I wanted, but I could sum it up as involving communal living in a rural setting, simplicity and as much self-sufficiency as possible, and the inclusion of other gay people and gay-friendly straights.”

You’ve done that well, my friend.