I missed The Flamingo Kid when the Garry Marshall movie came out in 1984, but I recently caught up with it. It’s a coming-of-age story that takes place in the summer of 1963, the era of Marshall’s TV series Happy Days and Laverne and Shirley. Although it was much admired at the time, today it looks, sounds and feels a lot like the teen flicks from that era, despite its social-commentary frame around class distinctions – that is, lots of sun-drenched exteriors with babes in bikinis, lots of teenage angst and predictable plot turns, and a soundtrack of hits from the Fifties and pre-Beatles Sixties.

Not exactly my cup of summertime fun, so I took my seat for Hartford Stage’s world-premiere version, a musical (running through June 15), with a mixture of misgiving and hope. The hope sprang from Hartford’s previous film-to-musical adaptation, A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder, derived from the classic Alec Guinness caper Kind Hearts and Coronets. I loved it, and so did the New York critics, audiences and Tony voters.

Not exactly my cup of summertime fun, so I took my seat for Hartford Stage’s world-premiere version, a musical (running through June 15), with a mixture of misgiving and hope. The hope sprang from Hartford’s previous film-to-musical adaptation, A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder, derived from the classic Alec Guinness caper Kind Hearts and Coronets. I loved it, and so did the New York critics, audiences and Tony voters.

Flamingo reunites two-thirds of the Gentleman’s Guide creative team. It’s directed by Darko Tresnjak (for whom this show is his farewell as the theater’s artistic leader) with book and lyrics by Robert L. Freedman, adapted from the screenplay. But the comparison ends there.

The previous premiere was a black comedy with an affably cynical plot about, well, love and murder, with a witty, tuneful score in which echoes of Noel Coward and music hall mingled with grand guignol. This one is simple and sunny, even less gritty than its cinema forebear, faithfully reproducing the movie’s conventional plot and sentimental nostrums. Scott Frankel is the composer this time, drawing inspiration not from the movie’s teen-pop soundtrack but from stage musicals of the Fifties – and I don’t mean West Side Story or My Fair Lady, but song-and-dance comedies like Damn Yankees and Guys and Dolls.

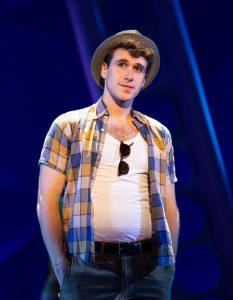

The story revolves around Jeffrey, a Brooklyn teenager, played with nerdy charm by newcomer Jimmy Brewer, who gets a summer job at the posh El Flamingo Beach Club on Long Island and has his working-class head turned by the swank surroundings and the beautiful Karla (an appealingly unaffected Samantha Massell), with whom he falls head-over-Keds in love at first sight.

The story revolves around Jeffrey, a Brooklyn teenager, played with nerdy charm by newcomer Jimmy Brewer, who gets a summer job at the posh El Flamingo Beach Club on Long Island and has his working-class head turned by the swank surroundings and the beautiful Karla (an appealingly unaffected Samantha Massell), with whom he falls head-over-Keds in love at first sight.

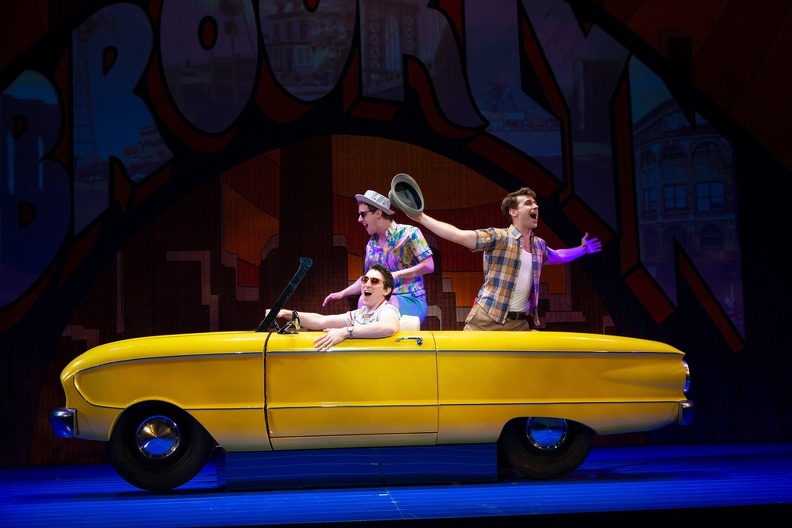

In a summer of life lessons, he learns that people aren’t always what they seem to be, that a “sure thing” at the racetrack isn’t always so sure, and that honesty and hard work are more valuable assets than fancy clothes and shiny cars (several tailfinned examples of which are onstage).

While Freedman adheres closely to the movie’s plotline, he makes the main characters Jewish, presumably with an eye to a hoped-for New York transfer (and for the New England crowd, there’s a glossary of Yiddishisms in the program). For modern sensibilities, he makes Karla not a blonde bimbo but a brainy brunette who’s reading Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, and for historical context he throws in references to the Apollo space program and the Cuban Missile Crisis.

The grownups in the piece represent the class distinctions that are at the heart of the show’s point of view. Karla’s uncle Phil (Marc Kudisch) is a flashy, self-absorbed bully who sells expensive cars and plays high-stakes gin rummy, and whose wife (Lesli Margherita) is an unhappy, bad-tempered tippler. Jeffrey’s mother (Liz Larsen) is a hard-working housewife whose husband (Adam Heller) is a hard-working plumber, proud of his profession, satisfied with his life, and outraged at his son’s pursuit of easy money and rejection of his roots.

Both these couples are strong and convincing, as are many of the youngsters, including Ben Fankhauser and Alex Wyse as Jeffrey’s freewheeling sidekicks. The 11-member supporting ensemble fills the stage with vibrant energy, costumer Linda Cho’s colorful beachwear and choreographer Denis Jones’ dance routines. The cast boasts marvelous singers who lift Frankel’s lively and serviceable but unmemorable score, to the accompaniment of an impressive 13-piece pit band.

Both these couples are strong and convincing, as are many of the youngsters, including Ben Fankhauser and Alex Wyse as Jeffrey’s freewheeling sidekicks. The 11-member supporting ensemble fills the stage with vibrant energy, costumer Linda Cho’s colorful beachwear and choreographer Denis Jones’ dance routines. The cast boasts marvelous singers who lift Frankel’s lively and serviceable but unmemorable score, to the accompaniment of an impressive 13-piece pit band.

Alexander Dodge’s dual-purpose set neatly illustrates the show’s class divide. An old-fashioned “Greetings from Brooklyn” postcard, projected onto a scrim, serves as backdrop to the humble blue-collar kitchen of Jeffrey’s home, rising as the scenes shift to reveal the glitzy chrome-accessorized El Flamingo.

In its final minutes, the show almost shoots itself in the tuchas, when the inevitable father/son reconciliation (everything in this show is inevitable) is followed by a long, redundant father/son ballad that almost kills the finale. But although the schmaltz flows freely throughout, the emotions are real and the performers attractive and affecting.

In its final minutes, the show almost shoots itself in the tuchas, when the inevitable father/son reconciliation (everything in this show is inevitable) is followed by a long, redundant father/son ballad that almost kills the finale. But although the schmaltz flows freely throughout, the emotions are real and the performers attractive and affecting.

I can’t predict if The Flamingo Kid will follow in the successful footsteps of Gentleman’s Guide. It certainly has less wit and originality, but maybe there’s enough Yiddishkeit, sentiment and razzle-dazzle to give it a life in New York, and an even longer one in community and high school theater.

The Stagestruck archive is at valleyadvocate.com/author/chris-rohmann

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email Stagestruck@crocker.com