Activists, elected officials, and concerned residents packed a June 5 Department of Energy Resources (DOER) hearing in Springfield on a state plan to open up state renewable energy subsidies to plants that burn biomass — mostly wood chips, wood pellets, and other wood products — which many said could result in poor health outcomes for the city of Springfield.

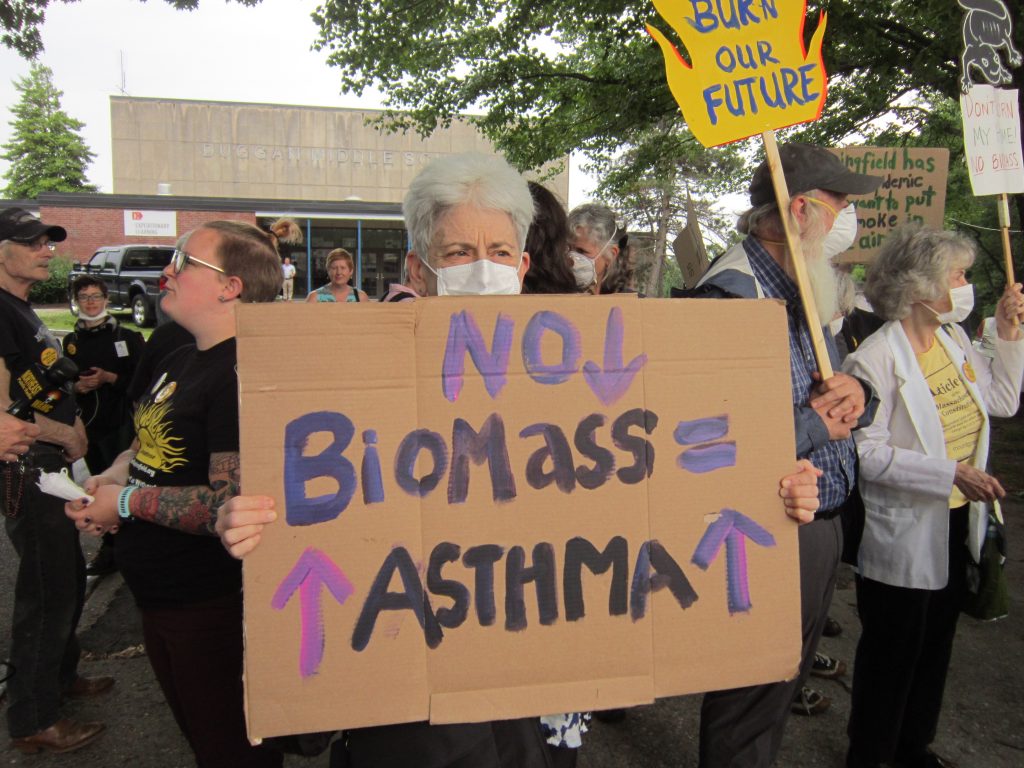

Adele Franks, 70 of Florence, was among the more than 100 people protesting a change which would allow biomass plants to gain clean energy credits.

Currently, solar, wind, hydroelectric, geothermal, and landfill methane gas are eligible for the subsidies.

At stake may be a return of a proposed Palmer Renewable Energy biomass plant planned for East Springfield. The $150 million 42-megawatt proposed plant has spent more than a decade stalled by legal battles, zoning concerns, and a Massachusetts Land Court case.

Tanisha Arena, executive director of Springfield grassroots activist group Arise for Social Justice, said at the hearing that the subsidies could incentivize the plant being built in the city, which has been named the worst U.S city to live in with asthma for the past two years by the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America.

“Biomass isn’t clean energy. Burning anything isn’t clean energy. Biomass plants emit more CO2 than other energy sources, so while y’all get money, Springfield gets higher rates of asthma, worse air quality than we already have, and a laundry list of other problems that come with the increased pollution. Would you want to breathe this air? When you leave here, you go back to Boston,” she told DOER officials. “I live here. My kids live here. My friends live here. We live here. We breathe what they burn, not you.”

Arena asked why biomass power plants aren’t being proposed in neighboring communities such as Agawam, Longmeadow, or East Longmeadow, adding, “Why is their ‘No’ stronger than mine. Don’t insult anyone’s intelligence in telling us that biomass is clean energy. We live in a time where pseudo-science focused on dollars and cents has taken the place of actual science and good sense.”

She views the proposed change that would allow biomass to become a renewable fuel source as “systemic genocide.”

“To continue to push to force [the biomass plant’s] placement in a community of black and brown people is blatant environmental racism,” Arena said.

From left, Springfield City Councilors Justin Hurst (president), Michael Fenton, Timothy Allen, Jesse Lederman, and Melvin Edwards speak out in opposition against the change allowing biomass to be eligible for state renewable energy subsidies.

About 150 people attended the high-spirited public hearing at the John. J. Duggan Academy auditorium, many of whom criticized the DOER and the Charlie Baker administration for the proposed change. Among them were five of Springfield’s 13 City Council members — Jesse Lederman, Melvin Edwards, Michael Fenton, Timothy Allen, and City Council President Justin Hurst.

Lederman, who is chair of the city’s Committee on Sustainability and Environment as well as the Committee on Health and Human Services, delivered an opening statement during the hearing.

“We stand before you, both surprised and disconcerted, that the state would be considering such an action in light of the clear empirical evidence that these type of large scale generation facilities are inconsistent with the Commonwealth’s stated goals for greenhouse gas reductions in the ongoing efforts to combat climate change,” Lederman said.

He added that the state commissioned a study completed in 2010 by environmental research company Manomet to investigate biomass power in Massachusetts, which found that biomass plants are not carbon neutral.

While the study said that forests could grow back over time to recapture the carbon put into the atmosphere, Lederman said that concerns over climate change are too immediate to wait for that.

Lederman chided the DOER for hesitating to hold a hearing in Springfield until the public comment period for the proposed change was nearly over. The comment period was planned to end on Friday, June 7, but was extended to July 26 by the DOER. Details on how to submit a public comment are at the end of the article.

Springfield is a state-designated “environmental justice community,” which according to state policies should allow for enhanced opportunities for residents to participate in environmental, energy, and climate change decision making, Lederman said.

But despite the city’s status and history with the proposed biomass plant, it wasn’t until members of the public, state legislators, and city council members requested the hearing that the DOER scheduled one, Lederman said.

“Because of this short notice, we would formally request that the deadline for written comments be extended to June 30 to allow adequate time for members of the public and our constituents to comment on the proposal,” Lederman said, which was followed by a loud applause.

Lederman added that all five councilors present, as well as three who were unable to make the hearing — Tracye Whitfield, Adam Gomez, and Orlando Ramos — endorsed the statement.

The Springfield DOER hearing was the final hearing among four that took place throughout the state, according to DOER Director Michael Judge. The other three hearings took place in Boston on May 13, at the University of Massachusetts Amherst on May 16 , and in Gardner on May 17.

In a statement from the Baker-Polito Administration requested by the Valley Advocate, Katie Gronendyke, a member of the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs, said the Baker-Polito Administration “remains committed to reducing the Commonwealth’s greenhouse gas emissions, meeting our targets under the Global Warming Solutions Act” as well as lowering energy costs for ratepayers through renewable energy technologies.

“We look forward to working with stakeholders during this open comment period,” Gronendyke stated.

Supporting the change

While most of the 60 people who spoke at the hearing spoke against the proposed change, several supported it.

John Clark, a licensed and practiced forester educated at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, said he thinks its increasingly important for carbon reduction to take place at the state level due to the federal government weakening environmental agencies.

“These fuels are renewable and will directly replace fossil fuels, leaving ancient carbon in the ground and utilizing biogenic carbon for our energy needs,” he said.

Charles Thompson, a resident of Hampshire County and a forester, said hundreds of thousands of pounds are generated throughout the Commonwealth every year by tree cutters, arborists, landscapers, and storm cleanup crewers, which could be used to fuel biomass plants.

“At present much of the wood sits and rots, gets dumped somewhere, or is actually trucked away at great expense to us all,” he said. “Indications are that the amount of wood in this category will increase in the future, whether from storm severity and frequency, loss from insects and diseases or utility operations to protect transmission lines.”

Thompson argued that the proposed change should go a step further and allow wood obtained through land clearing.

“No one is clearing land to just receive a renewable energy credit,” he explained. “The economics make no sense. This is wood that’s coming down anyway.”

Thomas Chamberland, tree warden for the town of Sturbridge for the past 35 years, said during the hearing that his community and others throughout the Commonwealth have stockpiles of wood biomass. The town of Sturbridge has its own stockpile of more than 4,500 cubic yards of wood chips with no place to dispose of them.

“There is no market, nowhere short of shucking it to Ohio to get rid of it,” he said. “This is becoming a community problem for every city and town.”

‘For the sake of the damn wood chips’

Bob Armstrong, a selectman from Conway, disagreed. He argued that the only thing keeping keeping dirty biomass plants from being built is the expense of burning it, and that subsidies could open the flood gates.

“I haven’t heard a single person in here promote these plants because they think making electricity with wood is a great idea,” he said. “We have a lot of greedy municipal people. We have foresters who are saying, ‘Oh, I can’t get rid of my wood chips.’ For the sake of the damn wood chips, we have to allow wood burners to make electricity subsidized by our ratepayers. This is ridiculous.”

Treating asthma for young children and elderly men and women is a daily reality for Dr. Martha “Marty” Nathan, a physician at Baystate Brightwood Health Center located at 380 Plainfield Street in Springfield.

“Springfield is the epicenter of the asthma epidemic plaguing Massachusetts,” she said. “Springfield is the most challenging city in the country to live with asthma. I am a family physician who treats mainly low-income, mainly Latino, elderly, working adults, and children — those most susceptible to the disease and the morbidity and its mortality.

She continued, “On any one day, I am likely to treat a toddler or a frail older person who comes in wheezing and in respiratory distress. If necessary, I send them to the hospital emergency room for stabilization or admission. They and their families are usually frightened and exhausted from nights without sleep from coughing and shortness of breath. The asthma rubber hits the road at Brightwood.”

Nathan said the proposed change would promote the burning of trees, which would result in her patients breathing in more particulate matter and make them sicker than ever.

“The irony is that they and all of us are paying for this,” she explained. “The funds for the renewable subsidies come from our energy bill and theirs. They who are disabled, underpaid, and often desperately poor. This is a terrible plan sacrificing my patients’ health and all of our climate future to subsidize the biomass industry. It is a violation of the public health and the DOER and the Baker Administration should be ashamed.”

Paula Nowick, a Springfield resident who lives about three miles from the proposed Palmer Renewable Energy biomass plant, has asthma. If she doesn’t carry her inhaler, she could have a sudden asthma attack and die.

She said she’s against the proposed change because it would make the creation of a biomass plant in Springfield easier, which would create more particulate matter pollution in the air that residents breathe.

For Michael Langone, a Springfield resident who lives nearby the proposed biomass plant and member of the Pioneer Valley Building Trades Council, building the plant would be a reason to support the change.

“This plant will provide a key source of reliable renewable base low power that we need as coal and nuclear plants are taken off line in Massachusetts,” he said. “This is not something that wind and solar can provide here in the Commonwealth. They are exactly the kind of green facilities that we should be building. Our members support these changes and would be proud to build these facilities anywhere in the Commonwealth. My members are all local people. They live here. They work here. They raise their families here in Springfield. I wouldn’t be testifying here today as a Springfield resident if I wasn’t confident behind the Springfield project and the safety and health of this project for me and my local members.”

Langone said he believes the proposed Springfield biomass plant would be critical for Pioneer Valley building trades people for work.

“This is a $150 million project that will employ well over 200 union tradesmen to build it, including teamsters, HVAC mechanics, pipe fitters, carpenters, sheet metal workers, electricians, steel erectors, concrete workers, plumbers, welders, mechanics, industrial maintenance people, and security,” he added. “It will also employ 50 full time workers when it’s complete.”

A rally in advance

Prior to the hearing, many held a protest rally outside of the school. About 100 people assembled and some held signs with slogans including “Welcome to Springfield, Asthma Capital of the U.S.” and “Don’t Burn Our Future.”

During the rally, City Council President Hurst responded to claims from local activists that building a biomass plant in Springfield would be environmental racism.

“The statistics bear it out,” Hurst told the Valley Advocate. “Blacks and Hispanics certainly suffer at higher rates of lung disease than their white counterparts. And if these facilities are in the city of Springfield, then once can certainly make the correlation that there is a problem with that … We need to do better. Other cities and towns throughout the Commonwealth wouldn’t want it in their area. Why should we have to have it in ours?”

During the hearing, City Councilor Edwards said his doctor told him that at some point in his life he’ll need to have a double lung transplant.

“So this is personal for me,” he said. “There is no way I can stand in support of anything that is spewing into our air … It will never be a benefit to my community except for the few jobs that it will create. And allow me to suggest that the majority of jobs, that in fact, will be created because of this plant or any other kind of plant of this nature will be at the Respiratory Department at Baystate Medical Center.”

UPDATE as of June 14, 2019: The DOER extended the deadline again for public written comments until July 26. The deadline was originally May 24, but was extended to June 7.

Written comments on the proposed change will be accepted until 5 p.m. on June 7, according to the DOER’s website. Written comments should be submitted to John Wassam electronically to DOER.RPS@mass.gov or via mail to the Department of Energy Resources, 100 Cambridge St., Suite 1020, Boston, MA, 02114.

Chris Goudreau can be reached at cgoudreau@valleyadvocate.com.