Dori Digenti does not know the criminal histories of her yoga students at the Hampden County Pre-Release Center.

“To me, they’re participants in a yoga class,” said the founder and owner of Breathing Space Yoga & Mindfulness Studio in Holyoke. “They’re just who they are.”

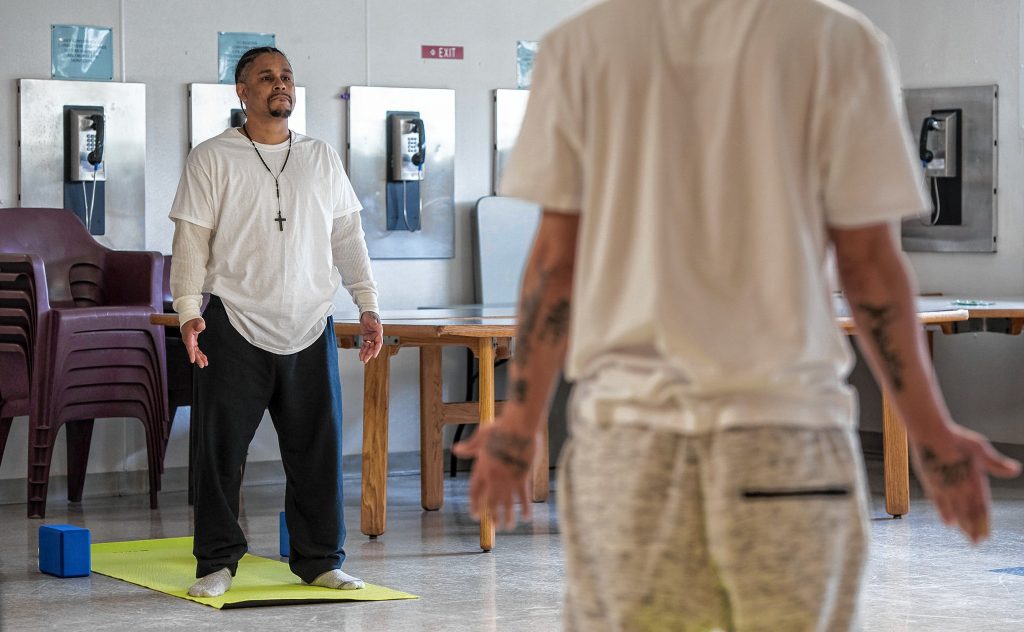

Steven, left, and Johnny, inmates at the Hampden County Pre-Release Center in Ludlow, assume a restorative pose at the end of a yoga class in the Cultivating, Honoring and Awakening Men’s Potential program, or CHAMP, on Tuesday, April 30, 2019.

The minimum-security institution where she volunteers once a week is on the same property as the Hampden County Jail and House of Correction in Ludlow. At the pre-release center, those sentenced by the courts begin the process of returning to their communities through residential and work release programs.

On a recent Tuesday morning there, Digenti started a yoga class by directing her students to mentally “scan” their bodies and make note of where they feel tension. When they exhale, she told them, imagine feeling that tension release. For a few minutes, the room was almost silent as everyone focused on their breathing.

Digenti is a teacher for the Prison Yoga Project, founded by James Fox at San Quentin Prison in California. Goals of the project include supporting incarcerated people with yoga and mindfulness and reducing recidivism.

Carlo, a student of Digenti’s who identifies as a “chronic relapser,” said he hopes to use the calming techniques learned from yoga to avoid relapsing into drug use. Pre-Release center policy restricted resident identification to first name only.

“I’m zero to 100 in half a second. I just react on how I feel,” he said. “I’m geared toward the instant gratification; I’ll deal with the consequences later. If there’s a buffer between my thoughts and how I react, I’ll be halfway there.”

A participant named Steven compares the focus and discipline of yoga to his experience as a martial artist. “This is almost just like it,” he said.

Participants say yoga releases tension and clears the mind. Steven said the yoga classes loosen the body and leave him “the most relaxed I’ve ever felt.”

“You know sometimes when you get tired and you want to take a nap? You just don’t want to deal with the rest of the day? This was actually like a nap — it replaced it,” he said.

Michael, another participant, said the yoga class sets a positive tone for the rest of his day.

“At first, you’re not so excited or willing to do it, and then after you start doing it, you get more used to doing it, and then you find other reasons to keep coming,” he said. “It makes you more positive during the day. It brightens up your day.”

Johnny, a participant in the program, said he was initially unenthusiastic about yoga, but now finds himself using the breathing techniques to deal with anxiety attacks.

“We’ve got to wake up noticing and realizing that we’re still incarcerated. Although we’re getting home, the anxiety kicks in … the eagerness to want to go home,” Johnny said. “Yoga just helps give us that peace of mind to just stay relaxed.”

In class

At Digenti’s recent class in Ludlow, eight men, ages 19 to 45, sat in a large circle on a white tiled floor. Under each participant were two blue blocks stacked on a yoga mat. At the front of the room, Digenti sat in a similar position.

Dori Digenti, center, begins a “Seeds to Flowers” yoga class with seven men enrolled in the Cultivating, Honoring and Awakening Men’s Potential program, or CHAMP, at the Hampden County Pre-Release Center in Ludlow on Tuesday, April 30, 2019. Digenti is owner and founder of Breathing Space Yoga and Mindfulness Studio in Holyoke.

“This is an opportunity to see — what can yoga do for me?” she told the group.

There was an introduction, during which each person in the circle, starting with Digenti, shared a first name and a reflection on the day so far. Digenti said she was enjoying the recent rain. Most of her students said they were good; one said he was “tranquil.”

Bill Brown, executive director of the national Prison Yoga Project, said he believes a key component of teaching in incarcerated settings is establishing a relationship of trust with the students, which includes keeping one’s privilege in mind.

“I come in as a free person,” he said. “How do we facilitate a level playing field so we’re not disempowering our students?”

Digenti’s classes last between 45 and 50 minutes. She asked her recent group if anyone had anywhere they needed to be. One participant joked that he has an appointment.

The transition from sitting to standing is done carefully. Digenti directed the participants to rise slowly from the blocks. Once standing, she told them to bend and straighten their knees a few times. She noted how when we stand, our knees often lock automatically, and told her students to keep their knees soft.

She guided them through the motions of lifting and spreading the arms, then reaching forward. She told them to “move with the breath” as much as possible. She reminded that the knees do not have to be straight during stretches.

“You don’t have to have a specific body type to do yoga,” Digenti said when reflecting on the class later.

The exercises are slow and deliberate, with Digenti instructing her students to inhale on some movements and exhale on others. The students reached out their arms and move the upper body in a slow circle. They swung their arms and twisted their hips. They stepped back with one foot and raised their hands into the “warrior” pose.

On coming out of warrior, Digenti told her students to exhale as they brought their arms down. “Beautiful,” she said.

She told her students to pay attention to their thoughts. Allow them to rise, she said, notice them and let them go. She tells them to imagine breathing out tension, stress, and old hurts.

The class ended with resting positions. Most of the men sat cross-legged. Digenti kneeled. One man lay on his back with his hands resting on his stomach.

Shawn, an inmate at the Hampden County Pre-Release Center in Ludlow, takes part in a yoga class in the Cultivating, Honoring and Awakening Men’s Potential program, or CHAMP, on Tuesday, April 30, 2019.

“We do a brief body scan to allow the body to release any remaining tension,” Digenti said. She noted that the resting pose, called Shavasana in Sanskrit, is a favorite for many.

‘It takes a lot of courage’

“Some of these guys are really tough guys,” said Michael Harrigan, a program supervisor at the pre-release center. “For them to leave their armor outside for a little while and come in and try something new, it takes a lot of courage and humility to do that.”

At the Hampden County Pre-Release Center, yoga is one component of the Cultivating, Honoring and Awakening Men’s Potentials — referred to by staff as CHAMP — program at the pre-release center. The initiative also includes structured times for reflection, substance use education, anger management, meditation and drumming, and resources for former drug dealers and hustlers.

Participants’ offenses include possession of a Class A drug, such as heroin or crack cocaine, with an intent to distribute and domestic violence-related charges, according to staff.

“It’s rare that we get somebody here who has nothing to do with drugs and alcohol,” said Harrigan, who supervises the CHAMP program.

The pre-release center had 110 residents as of this month, with the average stay being nine months. The capacity for the CHAMP program is now set at 18 residents. Inmates are referred to the program by their counselors.

Hampden County Sheriff Nicholas Cocchi expressed appreciation for the effect of the yoga classes so far.

“Sheriff Cocchi appreciates the good work of Dori and the very positive effect she has with her yoga on the inmates as they return to our communities,” said Steve O’Neil, the sheriff’s public information officer.

Lorna Edgar, a consultant for the Hampden County Sheriff’s department and creator of CHAMP, said she created the program with the goal of providing a safe atmosphere for individuals to explore the problems that led them to incarceration. The program has been at the pre-release center for a year and a half and has graduated more than 300 people. Statistics on recidivism, or repeat offenses, are not yet available due to the relative newness of the program.

Edgar said the mindfulness practices such as yoga, meditation, and drumming teach participants to become more aware of their thoughts and emotions and provide tools to stay present in the moment.

“If the participants can learn techniques to calm and self-soothe, they may find themselves less likely to overreact to situations that could lead them back into the legal system,” Edgar said in an email.

Nicole Hendricks, professor of criminal justice at Holyoke Community College, emphasized the importance of providing incarcerated people with enrichment opportunities, such as yoga and college classes. She noted that the path to incarceration often includes traumas such as sexual and domestic violence, and said mindfulness practices can be both therapeutic and rehabilitative.

“Any kind of tool that a person can use to navigate the challenges of reentry is going to be helpful, and we should equip them with as many tools to be successful as we possibly can,” Hendricks said.

She said ideally, the criminal justice system would be overhauled to become more humane and rehabilitative.

“I just see yoga as one of those ways to try to humanize what is for most people a very traumatic experience,” she said of incarceration.

A worldwide program

The Prison Yoga Project now has teachers in 28 states, as well as in Mexico, Canada, Europe, and India, and will launch a program in Israel this year, Fox said. He has been teaching at San Quentin Prison since 2002, and the project was established as a nonprofit in 2010, upon release of Fox’s book, “Yoga: A Path For Healing and Recovery.” More than 28,000 prisoners in the United States have requested and received this book free of charge, Fox said.

The Massachusetts chapter of the Prison Yoga Project formed in 2017, according to the state group’s website. A map on the national project’s website shows programs at the Berkshire House of Correction in Pittsfield, Women in Transition in Salisbury, and the Middleton House of Correction in Middleton in addition to the Ludlow pre-release center. In New England, there are also programs in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island.

The national Prison Yoga Project is supported by the Give Back Yoga Foundation, a nonprofit that brings yoga to marginalized populations, according to the foundation’s website.

On May 22, Digenti announced that her studio, a nonprofit, would be donating all profits to a newly established Seed to Flower Fund for Yoga Service, managed by the Community Foundation of Western Massachusetts. Digenti said goals for the Seed to Flower Fund include providing compensation for teachers providing trauma-informed yoga in Western Mass.

“We need armies of yoga teachers to do this work,” she said.

Prison Yoga Project teachers say the trauma-informed aspect is what sets their practice apart from other styles of yoga.

Steven, left, and Johnny, inmates at the Hampden County Pre-Release Center in Ludlow, take part in a yoga class in the Cultivating, Honoring and Awakening Men’s Potential program, or CHAMP, on Tuesday, April 30, 2019.

“The curriculum that most yoga teachers follow in becoming certified does not require that they learn about the nervous system — and we start there,” said Brown.

People who have experienced trauma often feel disconnected from their own bodies. Teachers of trauma-informed yoga specifically aim to bring participants in touch with the autonomic nervous system, which controls fight or flight. This can include being able to recognize when one is feeling triggered by a past trauma.

“The trauma-informed piece is about offering people a lot of options, to invite them to explore different aspects of the practice and how they feel in their bodies,” Digenti said.

Digenti said how she teaches each class depends upon her students. She may have a plan in mind, but after the first few poses, she observes how her students respond and adjusts if needed. She tells her students to hold poses only as long as they feel right. If a pose is uncomfortable from the start, she tells them to release it and wait for the next instruction.

The teachers say this style allows students to be in touch with their bodies and what they need. Brown said when teaching in an incarcerated setting, he does not use words of encouragement such as, “Your body is stronger than your mind thinks it is.”

“What if someone skipped lunch and is feeling weak?” he said. “Their experience is invalidated. We’re not teaching to the body. We’re teaching to the nervous system.”

Brown said more than 2,400 yoga teachers have been trained by the Prison Yoga Project, and he estimates more than 200 are now teaching in incarcerated settings.

Connecting mind and body

Houses of correction have other programs designed for residents’ stress-management. For example, the Hampshire County Jail and House of Correction has indoor and outdoor labyrinths for inmates to walk through. Like yoga, the goal of walking through the labyrinth takes advantage of the connection between the mind and body.

Donna Zucker, a professor in the College of Nursing at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, wrote the grants for the labyrinths.

“No one can actually clear their mind 100 percent,” Zucker said. “However, you can begin any kind of a meditation with an intention, and try to move that through the experience.”

She said activities such as labyrinth walking and yoga can help individuals learn impulse control, with which she notes people who have experienced significant stress often struggle.

“They don’t pause and think about, is this the best decision?” she said. “So that definitely is something that has to be unlearned, or at least they have to be aware of.”

Hendricks stresses that to further reduce recidivism, there is more work to do outside of jails and prisons.

“We have to address the structures that have the conditions under which either violence or crime occurs,” she said. “That’s a more structural problem, in my opinion.”

She names access to mental health services, treatment for addiction and affordable child care to be among areas in need of growth.

“If we’re not doing all of those things on the outside, mindfulness is not going to be enough,” she said. “Not saying it’s not an improvement, but I wouldn’t stop there, is what I’m saying.”