More than any other summer theater festival in these parts, Williamstown thrives on stars. For the theater it’s a sure-fire audience and income generator, but for the stars it’s an opportunity. Here they can dig into roles they might not otherwise be offered, and stretch their talents beyond what the public expects.

Two fixtures of network TV are opening the season at the Williamstown Theatre Festival in two quite different plays that have a lot in common. S. Epatha Merkerson (Law & Order, Lackawanna Blues, the Chicago franchise) headlines a revival of A Raisin in the Sun and Andre Braugher (Homicide:Life on the Street, Brooklyn Nine-Nine) plays a convict instead of a cop in a world premiere, A Human Being, of a Sort.

A Human Being, of a Sort – the very title chills – is based on a historical episode from the early 20th century, in which an Mbuti man from the Belgian colony laughably known as the Congo Free State was brought to the United States and exhibited as a curiosity at the St. Louis World’s Fair and then in the Bronx Zoo. The man’s name was Ota Benga, a pygmy whose tribe was decimated and his family killed by Belgian forces.

Jonathan Payne’s play depicts actual people and events, up to a point. William Hornaday, the zoo’s director (white, of course), really did believe he was doing a service to ethnography and anthropology; the black clergyman Rev. James Gordon and others really did campaign for the man’s release; Benga himself really did occupy an exhibit in the Monkey House; and a black man really was his keeper. Payne has extrapolated from those facts, adding invention to actuality – a revisionist act, perhaps, but one that gives the play a riveting dramatic conflict and cascading layers of meaning.

Jonathan Payne’s play depicts actual people and events, up to a point. William Hornaday, the zoo’s director (white, of course), really did believe he was doing a service to ethnography and anthropology; the black clergyman Rev. James Gordon and others really did campaign for the man’s release; Benga himself really did occupy an exhibit in the Monkey House; and a black man really was his keeper. Payne has extrapolated from those facts, adding invention to actuality – a revisionist act, perhaps, but one that gives the play a riveting dramatic conflict and cascading layers of meaning.

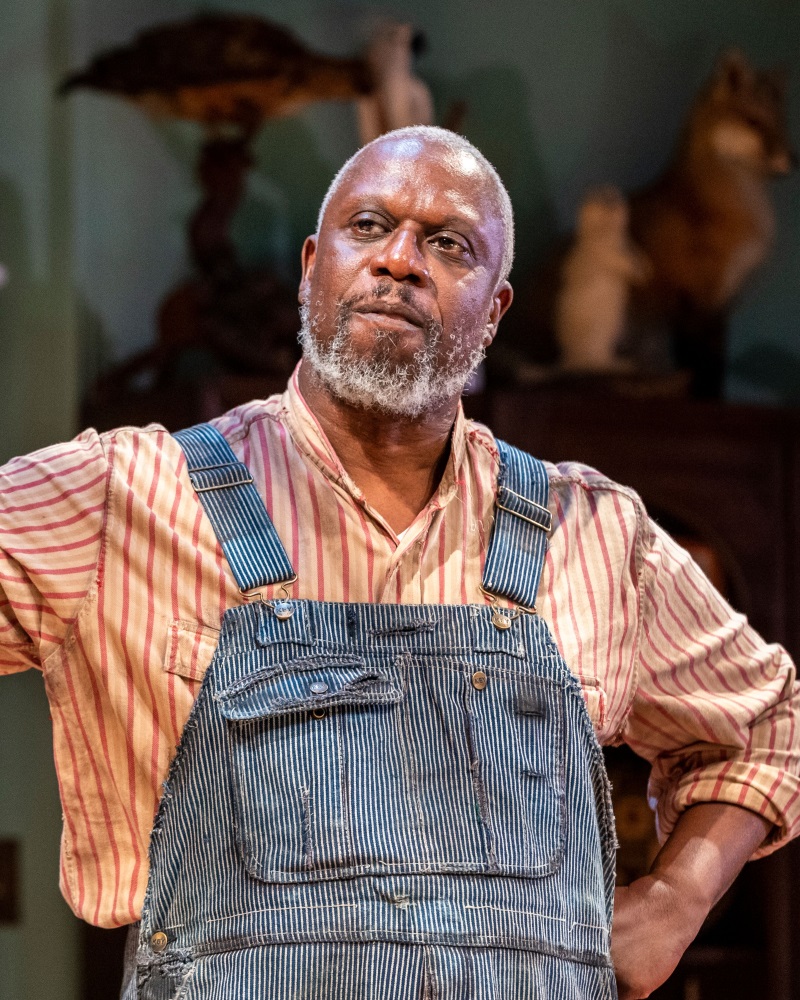

The wholly invented character is Smokey (Braugher), sent to Hornaday on a kind of work-release from a southern chain gang. This too is based on history, as “convict leasing” was common in the post-Reconstruction South, providing not only profit for the penal system but incentives for imprisoning poor black men for minor offenses – a practice clearly reflected in today’s for-profit prisons and mass incarceration.

Smokey is tasked with supervising his charge’s nine-to-six exhibition schedule and keeping the zoo’s “guest” contented and obedient. Smokey’s freedom-of-a-sort depends on Benga’s confinement – the threat of being returned to the prison farm constantly hangs over him. The two men, both sentenced to indentured servitude, develop a mutual understanding, not quite a friendship, based on their mutual captivity.

Smokey is tasked with supervising his charge’s nine-to-six exhibition schedule and keeping the zoo’s “guest” contented and obedient. Smokey’s freedom-of-a-sort depends on Benga’s confinement – the threat of being returned to the prison farm constantly hangs over him. The two men, both sentenced to indentured servitude, develop a mutual understanding, not quite a friendship, based on their mutual captivity.

Lawrence E. Moten III’s set combines two locations in the zoo: Hornaday’s office, a wood-paneled space whose walls are lined with display cabinets and studded with trophy heads, and within that space, looming large, Ota Benga’s cage, a cube of metal bars strewn with straw and littered with bones.

Rather than milking his horrific subject for melodramatic effect and a simplistic message, Payne has drawn three complex, conflicted characters, and director Whitney White has sensitively brought out their humanity along with their contradictions. Frank Wood’s Hornaday is a decent man with abolitionist credentials whose compassion is tempered by fiscal considerations and blinkered by the science of the time, when the embrace of Darwinism placed Africans a notch below “humans” on the evolutionary scale.

Smokey, in Braugher’s agonizingly moving performance, toes a highwire between fear of return to the chain gang and empathy with his captive. Antonio Michael Woodard is wonderful as Ota Benga – angry and lonely in his imprisonment, sassy and mocking in his performance for the crowds, resourceful in his attempts at freedom.

Smokey, in Braugher’s agonizingly moving performance, toes a highwire between fear of return to the chain gang and empathy with his captive. Antonio Michael Woodard is wonderful as Ota Benga – angry and lonely in his imprisonment, sassy and mocking in his performance for the crowds, resourceful in his attempts at freedom.

The trio of black clerics led by Rev. Gordon (Jeorge Bennett Watson, Sullivan Jones and Keith Randolph Smith) are not at all conflicted. To them, displaying Ota Benga is quite simply an offense against morality and humanity. Their onstage confrontations with Hornaday, alternating between outrage and negotiation, are backup up by offstage strategies to inflame the press and public.

This is the play’s first outing, and it still wants cutting. Most of the scenes go on longer than necessary, and the extended two-act structure diminishes its effectiveness. Benga has a monologue in which he addresses the audience to reveal his inner thoughts, and there’s a coda flashing back to his first encounter with the white explorer who brought him to America. Both are moving, but neither one tells us anything we’ve not already learned from exposition and context.

That said, the play is a powerful piece that turns a bright light on the historical past and our own time, without sensationalizing or devaluing either one. It plays in WTF’s Nikos Theatre through July 7.

A place in the sun

WTF’s current production of Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun (on the main stage through July 13) comes on the 60th anniversary of its debut on Broadway, and the show’s publicity reminds us that it was the first play by an African-American woman to appear on the Great White Way. But in a pre-opening interview, director Robert O’Hara insisted he has “no interest in doing museum pieces. I think all classic plays should be treated as new plays. I have interest in doing plays that speak to us now.”

Certainly Raisin’s story of the Younger family, caged in a rundown apartment on Chicago’s South Side and yearning for a better, freer life, echoes down to our own day, no matter how you treat it. Lena, the matriarch, receives a $10,000 payout on her deceased husband’s life insurance and plans to invest it in a home in the suburbs, fulfilling her dream of a yard and a garden. She’s putting some of it aside for her daughter Beneatha’s dreamed-of medical school education, while her son Walter Lee, sick of the humiliation of being a white man’s chauffeur, dreams of investing in his own business.

Certainly Raisin’s story of the Younger family, caged in a rundown apartment on Chicago’s South Side and yearning for a better, freer life, echoes down to our own day, no matter how you treat it. Lena, the matriarch, receives a $10,000 payout on her deceased husband’s life insurance and plans to invest it in a home in the suburbs, fulfilling her dream of a yard and a garden. She’s putting some of it aside for her daughter Beneatha’s dreamed-of medical school education, while her son Walter Lee, sick of the humiliation of being a white man’s chauffeur, dreams of investing in his own business.

The play’s title comes from Langston Hughes: “What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up, like a raisin in the sun? Or fester like a sore, and then run?” In Hansberry’s now-iconic masterpiece, dreams, ambitions, and fantasies clash against necessity and reality in events that resonate today, especially in black and immigrant communities. To that end, O’Hara has refocused and re-envisioned the play, partly with lighting effects (by Alex Jainchill) that highlight moments of memory and aspiration, but largely by adding a character and breaking the traditional fourth wall.

In the script, Lena’s husband, Big Walter, is often evoked – a hard-working man who worked himself to death in the care of his family. Here, when he’s recalled, he appears, a silent presence seen by Lena in her mind’s eye. The effect works well, animating the man’s contribution to the family’s past and hoped-for future.

Not so effective, I thought, is Walter Lee’s monologue of defiance and despair, which is given a downstage spotlight for a literal finger-pointing at the mostly white audience – not because we don’t deserve it, but because it implies that the play isn’t delivering its own message. The speech is further compromised by O’Hara’s choice to draw out Walter Lee’s reliance on alcohol to fuel his fantasies and dull his pain, so that at this and another pivotal moment, when he should be channeling his father, he appears drunk and thus diminished.

Not so effective, I thought, is Walter Lee’s monologue of defiance and despair, which is given a downstage spotlight for a literal finger-pointing at the mostly white audience – not because we don’t deserve it, but because it implies that the play isn’t delivering its own message. The speech is further compromised by O’Hara’s choice to draw out Walter Lee’s reliance on alcohol to fuel his fantasies and dull his pain, so that at this and another pivotal moment, when he should be channeling his father, he appears drunk and thus diminished.

The cast is across-the-board terrific. Nikiya Mathis’ Beneatha, burning with proto-feminist fire, is the perfect foil for her two would-be lovers, an overconfident business major (Kyle Beltran) and an elegant Nigerian prince (Joshua Echebiri). Eboni Flowers is appropriately blowsy as the nosy, noisy neighbor whose one (gratuitous) scene was cut from the original production and has rarely been seen since. Owen Tabaka, as the 10-year-old son of Walter Lee and his wife Ruth, is a child actor who can act.

While O’Hara has moved Walter Lee closer than usual to the center of the play – and Francois Battiste’s performance is both scary and heart-wrenching – it’s not at the expense of the others. Here, Ruth emerges from the relative shadow she’s often in, largely thanks to Mandi Masden’s penetrating portrait of the woman: not merely long-suffering and endlessly forgiving but spirited, witty and in her own way self-sufficient.

While O’Hara has moved Walter Lee closer than usual to the center of the play – and Francois Battiste’s performance is both scary and heart-wrenching – it’s not at the expense of the others. Here, Ruth emerges from the relative shadow she’s often in, largely thanks to Mandi Masden’s penetrating portrait of the woman: not merely long-suffering and endlessly forgiving but spirited, witty and in her own way self-sufficient.

Merkerson is slighter and quieter than many Lenas before her, but her understated performance carries the weight of the play along with the family’s trajectory. Take a moment to watch her when she’s watching the others, her face a shifting field of emotions that maps the history of black women from 1959 and before, all the way up to today and beyond.

As A Human Being’s director, Whitney White, observes in a program interview, “The past is now.”

Photos by Jeremy Daniel & Joseph O’Malley

The Stagestruck archive is at valleyadvocate.com/author/chris-rohmann

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email Stagestruck@crocker.com