“Who knew?” is the question in the air these days at Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival. For example: Who knew that many of the great Duke Ellington’s compositions were written by someone else? And who knew that the pious religious community known as Shakers had African-American members?

Last week, the LA-based dance troupe David Roussève/Reality performed Halfway to Dawn, a celebration of the unjustly obscure Billy Strayhorn. For four decades, Strayhorn wrote or co-wrote almost everything in the Duke’s repertoire, often without credit. In recent years, Strayhorn has begun getting his due, and Roussève’s wide-ranging biography-cum-tribute adds to that recognition, using words and images, music and movement to detail his life and times and bring his creative ownership out of the shadows.

Accompanied by classic and new recordings of Strayhorn’s compositions and collaborations with Ellington, and by black-and-white projections (not always useful), the piece takes us through the chronology of his life, from his Pittsburgh upbringing through his decades-long association with the great bandleader, to his death from cigarettes and alcohol in 1967 at age 51.

It begins with a joyous joint-is-jumping number that showcases the ebullient nine-member ensemble, which boasts an exhilarating diversity of colors, body types and ages. But an air of loneliness and anguish winds through the piece. “Take the A Train,” Ellington’s signature number, is given an almost dirge-like treatment, and the luxurious “Lush Life” is a cacophony of multiple recordings.

It begins with a joyous joint-is-jumping number that showcases the ebullient nine-member ensemble, which boasts an exhilarating diversity of colors, body types and ages. But an air of loneliness and anguish winds through the piece. “Take the A Train,” Ellington’s signature number, is given an almost dirge-like treatment, and the luxurious “Lush Life” is a cacophony of multiple recordings.

Two ironic tropes keep recurring – a sarcastic minstrel showing slo-mo jazz hands and dolefully repeating, “Party, party, fun, fun, fun,” and a sad clown, his face painted to hide the tears – apparently a metaphor for Strayhorn living the lush life while dying inside. The overarching theme is disappointment: frustration with the boss’s cavalier treatment of his work and discontent with his place in the background.

Which is a little surprising, since some important parts of Strayhorn’s life were proudly public. He was an openly gay man in a deeply closeted era, and a Civil Rights activist, a friend of Dr. King. Halfway to Dawn ends with two tracks from Ellington’s tribute album to Strayhorn, both of them wistful numbers that rise and curl like the smoke in a late-night club.

Fists and Heels

When Reggie Wilson founded his dance company 30 years ago, he named it Fist and Heel, after the only percussion instruments enslaved Africans were allowed in the early days of their captivity in the New World. His work is informed by cultural and historical research throughout the African diaspora, which is what led to the creation of the piece he’s premiering at Jacob’s Pillow this week, POWER.

In this case, the term refers to the power of the Lord. Wilson’s discovery that there were black Shakers in some of the sect’s 19th-century communities led him to look deeply into their lives in those communitarian villages, including the ones in New Lebanon NY, and Hancock MA, just outside Pittsfield. They were a mix of enslaved and free black people, some of them drawn by the Shakers’ egalitarian philosophy, and some, in slave states like Kentucky, brought along when their owners joined the community, living in comparative freedom within the village limits but still legally property.

Last weekend Hand and Fist performed a companion piece to POWER, a site-specific presentation in the majestic round stone barn at Hancock Shaker Village. It was called …they stood shaking while others began to shout, a fusion of movement inspired by Shaker, Black Baptist and Yoruba worship traditions, with a rather odd soundtrack.

Last weekend Hand and Fist performed a companion piece to POWER, a site-specific presentation in the majestic round stone barn at Hancock Shaker Village. It was called …they stood shaking while others began to shout, a fusion of movement inspired by Shaker, Black Baptist and Yoruba worship traditions, with a rather odd soundtrack.

Wilson has called his works “post-African/Neo-Hoodoo modern dances,” and describes fist-and-heel as “clapping and stomping, shouting and hollerin’, and the manipulation of energies.” That’s what the ten dancers, mostly African-American, did in the 45-minute performance: now stooping to “shake out sin” through their hands, now reaching heavenward in praise, now convulsed with the holy spirit. The recorded music included African-derived rhythms, but also Gladys Knight’s medley of two plain-vanilla songs, “Try to Remember” from The Fantasticks and “The Way We Were,” plus a reggae version of “Ring of Fire.”

In POWER, this week in the Pillow’s intimate Doris Duke Theatre, we’ll see the fully staged culmination of Wilson’s scholarly researches and creative explorations with his company, an imagined reconstruction of what black worship might have looked like in Shaker communities.

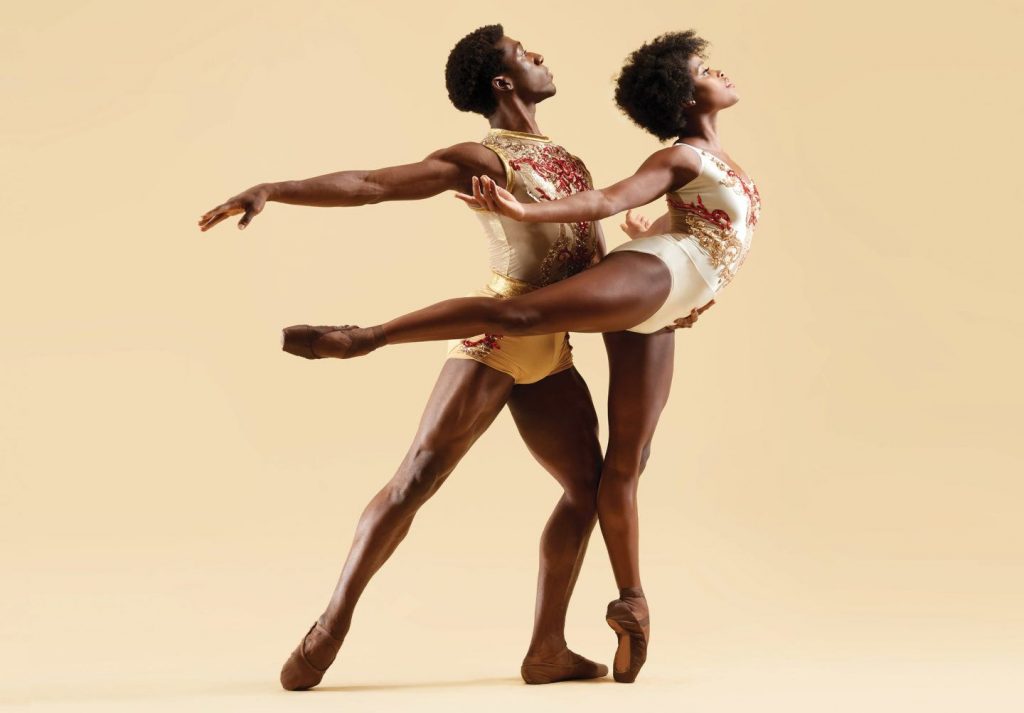

Concurrently, on the Pillow’s mainstage, African-American traditions get a corresponding modern-dance treatment from the Dance Theatre of Harlem. The program commemorates the company’s 50th anniversary and the life of co-founder Arthur Mitchell, who died last year.

Concurrently, on the Pillow’s mainstage, African-American traditions get a corresponding modern-dance treatment from the Dance Theatre of Harlem. The program commemorates the company’s 50th anniversary and the life of co-founder Arthur Mitchell, who died last year.

The iconic troupe’s program includes gems from its repertoire and a Pillow premiere. There’s Darrell Grand Moultrie’s Harlem on My Mind, Christopher Wheeldon’s This Bitter Earth, George Balanchine’s Valse Fantaisie, and a new, expanded version of Balamouk, by Jacob’s Pillow Dance Award winner Annabelle Lopez Ochoa.

As ever, there are daily free Inside/Out performances and pre-performance talks by the Pillow’s resident scholars and visiting experts.

Wednesday-Sunday, Jacob’s Pillow, George Carter Road, Becket MA. Info at jacobspillow.org.

Photos: Halfway to Dawn – Christopher Duggan

Fist and Heel – Ian Douglas

Dance Theatre of Harlem – Rachel Neville

The Stagestruck archive is at valleyadvocate.com/author/chris-rohmann

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email Stagestruck@crocker.com