Two timely dramas are playing in the Valley this week and next, while a timeless tragedy is prequelled in the Berkshires, all of them grappling with essential questions of life and death.

New Century Theatre’s comeback season, which opened with a riveting performance of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? closes with Lee Blessing’s Tony-nominated and Pulitzer-finalist A Walk in the Woods (at Eastworks, July 26-August 4). It’s inspired by a real historical moment, when two negotiators, American and Soviet, chatted their belligerent nations toward an arms-control agreement. Critics have called the play “brilliant and wryly humorous” and, despite its Cold War origins, “just as relevant as ever.” The production, directed by Sam Rush, features Valley veterans Jaris Hanson and Sam Samuels.

At Chester Theatre Company, Martin Zimmerman’s On the Exhale (July 25-August 4) stars Tara Franklin, a longtime Berkshire favorite. She plays the mother of a child murdered in a school shooting, whose furious grief turns into an obsession involving the killer’s weapon of choice. As artistic director Daniel Kramer said recently, “You may look at the subject matter of On the Exhale and think to yourself, ‘I don’t know if I want to see that.’ Please, think again.” Its topic, though shocking, couldn’t be more insistently necessary, “exactly the kind of work that Chester Theatre Company is here to create.”

At Chester Theatre Company, Martin Zimmerman’s On the Exhale (July 25-August 4) stars Tara Franklin, a longtime Berkshire favorite. She plays the mother of a child murdered in a school shooting, whose furious grief turns into an obsession involving the killer’s weapon of choice. As artistic director Daniel Kramer said recently, “You may look at the subject matter of On the Exhale and think to yourself, ‘I don’t know if I want to see that.’ Please, think again.” Its topic, though shocking, couldn’t be more insistently necessary, “exactly the kind of work that Chester Theatre Company is here to create.”

Gertrude and Claudius, at Barrington Stage Company through August 3, begins with the marriage of a 17-year-old princess to the future Danish king and ends 30 years later in Act 1 scene 2 of Hamlet. It’s Mark St. Germain’s dramatization of John Updike’s novel, which imagines the events leading up to the murder of the king by his brother, who then seizes his throne and marries his queen.

The play is not so much an adaptation as a condensation. Much of the dialogue comes directly from the pages of the book, and the plot faithfully, sometimes over-faithfully, follows Updike’s narrative thread, from Gertrude’s political marriage at her father’s will in order to preserve the royal line, through a growing attachment to her stolid husband’s adventurer brother, and finally into a dangerous infidelity – a scenario inspired by hints in Shakespeare’s text.

Updike’s strong storyline provides a sturdy frame for the drama, which is a good thing, as St. Germain is primarily a playwright of ideas, which may well be what attracted him to the work. Updike’s book is in part a meditation – on kingship and kinship, compunction and conscience, freedom and possession. Here the ideas flow as fast as the action. The characters often speak in epigrams and the script is studded with metaphors, many also lifted whole from the novel. Two gifts to Gertrude provide a leitmotif – a pair of caged lovebirds, and a falcon, a female raptor captured and slowly bent to man’s will – and there’s a chilling coup de theâtre that brings the two together.

The playwright thankfully dispenses with Updike’s extensively regurgitated research into Danish history (the novel’s characters even change their names sequentially, starting with Shakespeare’s medieval sources and finally landing on those in Hamlet). St. Germain also places the story in Shakespeare’s own time, cueing us to it with a reference to an early Elizabethan comedy and introducing a 16th-century artwork, Titian’s Penitent Magdalene – the fallen woman, another apt allegory – which Gertrude is copying in needlework.

The playwright thankfully dispenses with Updike’s extensively regurgitated research into Danish history (the novel’s characters even change their names sequentially, starting with Shakespeare’s medieval sources and finally landing on those in Hamlet). St. Germain also places the story in Shakespeare’s own time, cueing us to it with a reference to an early Elizabethan comedy and introducing a 16th-century artwork, Titian’s Penitent Magdalene – the fallen woman, another apt allegory – which Gertrude is copying in needlework.

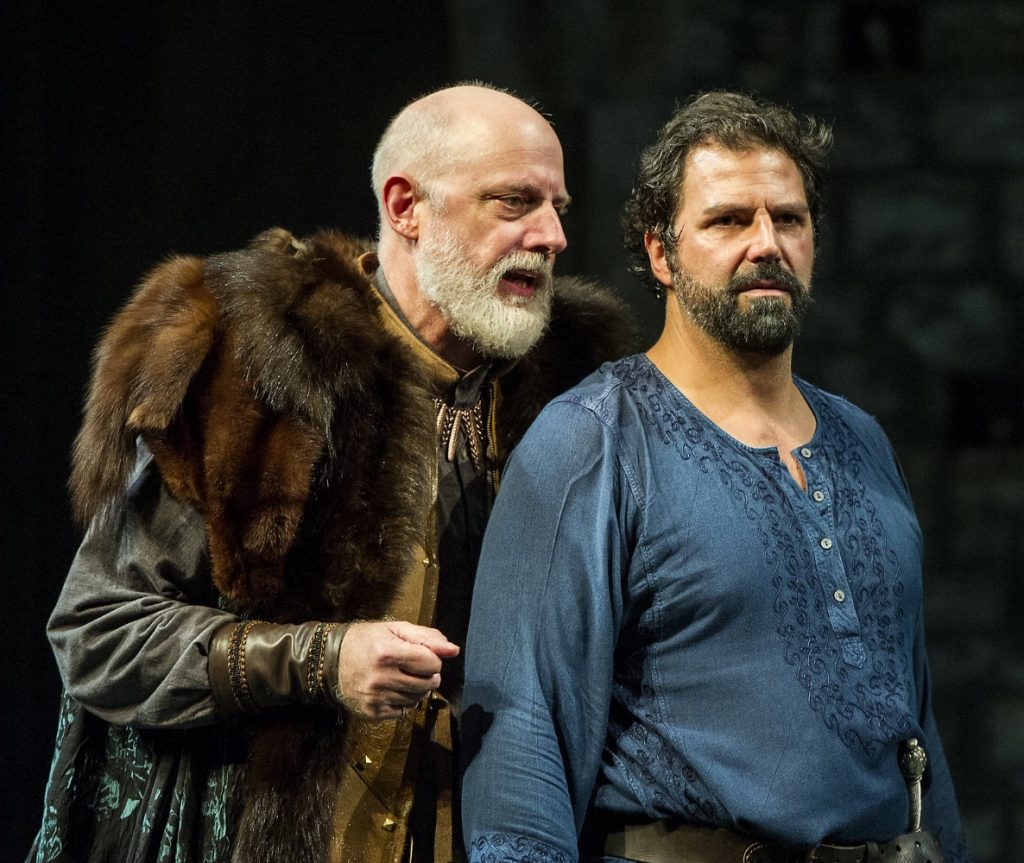

Julianne Boyd’s production is brisk and engrossing, a costume drama driven by breathless tension. It’s also beautifully designed. Lee Savage’s set is an arched gallery of gray stone inset with votary candles and topped by crumbling battlements, with moody lighting by David Lander. Costumer Sara Jean Tosetti drapes the royal brothers in animal skins and chain mail, and Gertrude in brocade and velvet, Byzantine silk and ultimately, adulterous scarlet.

Polonius, the garrulous old chamberlain, is a co-conspirator in the clandestine affair (Rocco Sisto’s sly poker face says it all). Updike’s invented character Herda, Gertrude’s lady in waiting, is also a collaborator, and Mary Stout’s wonderfully mobile face gives the play some comic relief.

Ophelia is only an offstage presence, but Yorick the jester appears, equated with the boy Hamlet (both played by Nick LaMedica). Shakespeare’s title character is only a walk-on, a mischievous child and unruly adolescent who avoids his mother (a theme explored more fully and poignantly in the novel).

Kate MacCluggage’s Gertrude is a luminous but level-headed beauty, aware that her status is owed to politics, not pulchritude. She’s too smart to be satisfied as the mere consort of a distracted monarch but too cautious to leap into an impetuous liaison. Updike emphasizes that when the illicit lovers finally join they’re in their forties, and while MacCluggage’s Gertrude grows in gravitas she doesn’t physically age.

Not so Douglas Rees, as King Amleth, whose long blond mane gives way to a bald pate (and, unaccountably, short back and sides). Just a ghost in Shakespeare, here Hamlet’s father is alive and powerful, fond of his queen in a proprietorial way but his passion given to husbanding the kingdom.

Not so Douglas Rees, as King Amleth, whose long blond mane gives way to a bald pate (and, unaccountably, short back and sides). Just a ghost in Shakespeare, here Hamlet’s father is alive and powerful, fond of his queen in a proprietorial way but his passion given to husbanding the kingdom.

In Claudius we find, not Shakespeare’s “smiling, damned villain,” but a spirited, resourceful man, neither casual seducer nor malicious killer. Ever in his elder brother’s shadow, he constantly ventures abroad, first as a “diplomat” (that is, a spy) then to escape his unquenchable attraction to the queen. Elijah Alexander brings intelligence and charm to this most transformed of Shakespeare’s characters, and he forges with MacCluggage an aching bond that tantalizingly simmers before boiling over.

Both the novel and the play are sprinkled with glancing quotes from Hamlet, and at the end both employ verbatim lines of dialogue. This is less effective in St. Germain’s version, where the slightly heightened vernacular suddenly gives way to thee’s and thou’s, then veers into a curtain line that’s supposed to suggest Macbeth but comes off like Capone. It’s a small jarring note that barely disturbs this captivating prologue to the world’s most famous finale.

Gertrude and Claudius photos by Daniel Rader

The Stagestruck archive is at valleyadvocate.com/author/chris-rohmann

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email Stagestruck@crocker.com