Woodblock printmaker, sculptor, and quilter Eli Liebman and I went for a walk recently. Traversing the edge of North Street to the dike in Hadley, Liebman was fixated on the implied violence lurking beneath the surface of quaint, suburban life — from the colonial violence of settler expansion to the imperial projects that bleed the earth of oil and minerals. As we teetered on the edge of the road, between passing cars and farm fields, an SUV passed by and he turned to me and passionately commented on the proto-fascist-militarism needed to fill the gas tank and sustain life in the cul-de-sac.

When we went for this walk, Liebman was preparing for a show that is going up at A.P.E. Gallery on July 28 in Northampton that deals the false security of a what he dubs a “state of violence.” Liebman, 26, was wearing a tattered gray hoodie, fraying black work pants, and shower style flip flops, cloaking his scrawny frame and exposing a thick plume of black hair atop his head. Despite an unserious look, Liebman takes art extremely seriously, with an eye for the unsavory facets of frontiers and empire, life and death, in a perpetual state of silent, digitized warfare — the type of stuff most people seldom think about or even acknowledge.

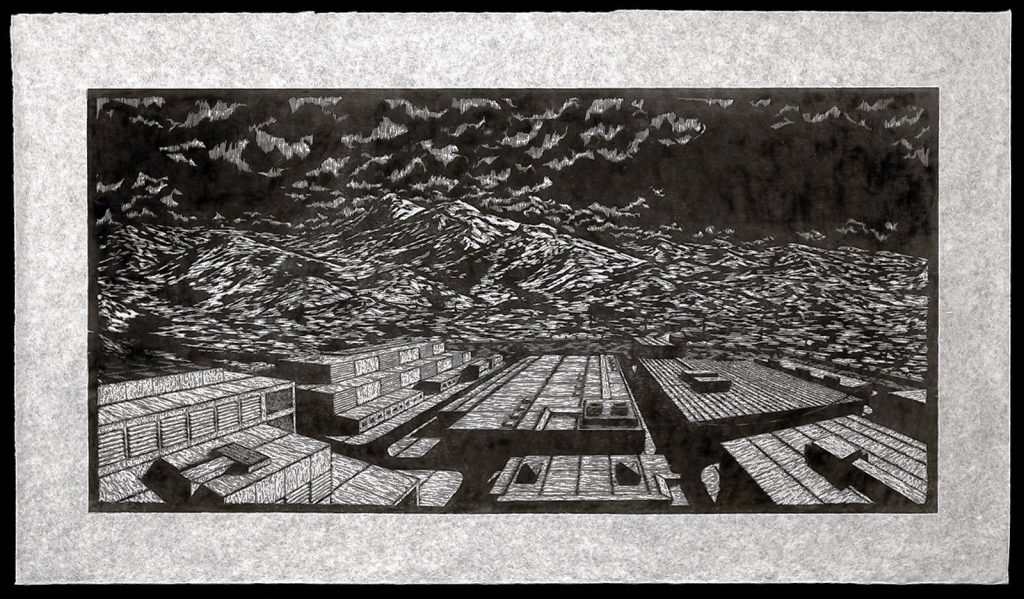

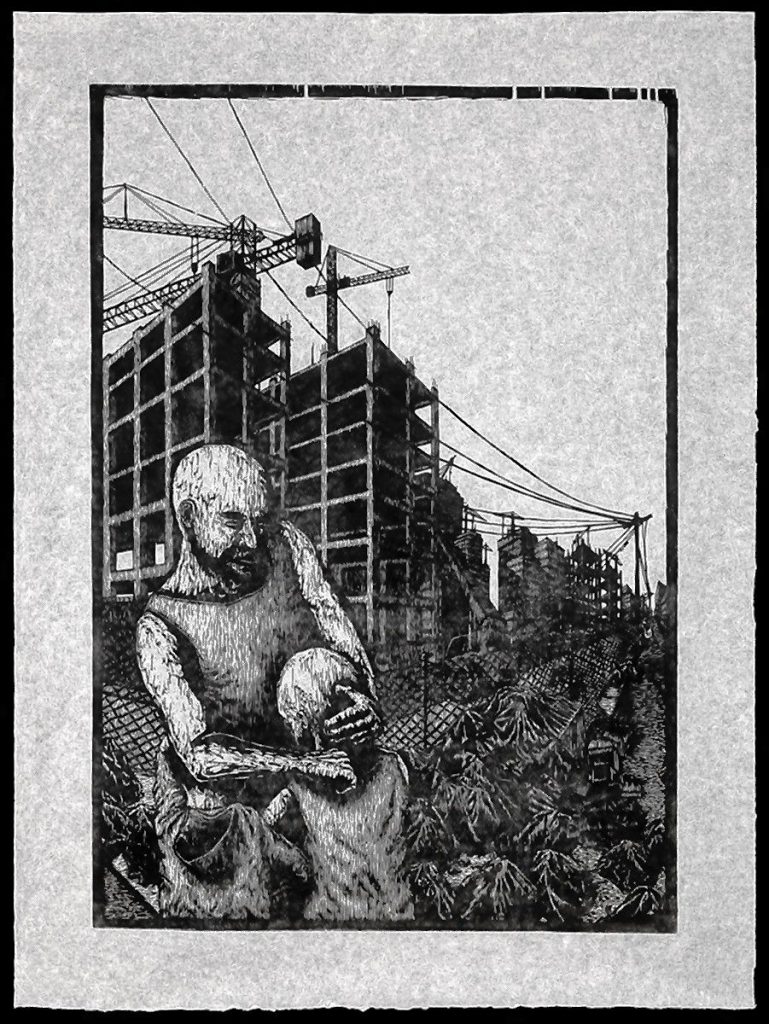

Liebman titles his woodblock prints in a way that uses a morbid humor to juxtapose imperial violence with consumer comforts. One print, titled “Unlimited Streaming,” depicts an NSA data center in Utah that collects “digital pocket litter” — email, financial transactions, and cell phone metadata. Another, wryly titled “Kickstarter,” shows a father embracing a child in front of cranes recreating a neighborhood. In his artist statement, Liebman writes, “the print also points to Li Hua’s prints, Fleeing Refugees, suggesting that displacement is often a manufactured crisis tied to the built environment.” Liebman’s printmaking follows the tradition of woodblock relief printing, which is often associated with social movements such as the Mexican revolution, German expressionism, and postwar printmaking in Japan. Liebman explained that he hoped to use an old school medium with a rich history in social protest in order to convey historical and technological changes that wouldn’t (or couldn’t) endure the way that woodblock printing has.

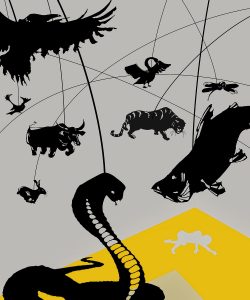

Another piece in Liebman’s show is a mobile depicting various animals that have emerged as “contemporary icons of Capital emerging at the crescendo of the eradication of flora and fauna.” In the statement, he writes “The viewer sees the mobile suspended in a world where the rise of corporate Amazon mirrors the ecological Amazon’s eradication.” The piece titled “Safariland: Capital’s Menagerie” is named after Safariland, a firm that creates “less lethal” security technologies like tear gas, rubber bullets, and batons. Hanging from the mobile is a cobra (representing the subsidiary of a fossil fuel company that manages the Puerto Rican electric grid), a tiger, and a swan (from TigerSwan a mercenary security firm that surveilled water protectors at Standing Rock), among others.

One the central ideas, spanning mediums and multiple pieces, is the idea of a security blanket — two prints and a quilt share this title. The blanket and the mobile signify objects of childhood, and asks the question of the future for children for children growing up in a world both brutal and abstract violence and death — the horrors a blanket won’t cover.

Eli Liebman’s Show “Security as a State of Violence” will be showing at A.P.E. from July 28 to August 11, with an opening reception on August 3 at 7 p.m.

Will Meyer writes the twice monthly Basemental column.