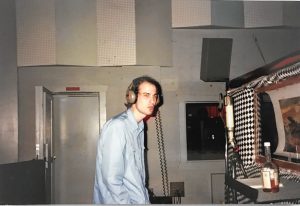

For a long time, he was unsure of his singing voice, wondering if it was really good enough to front a band. And for a good part of the time he was making albums, he also shunned most live performances, not feeling he could sing in front of an audience.

But David Berman, who committed suicide last month, had a gift for words — whether in his songs or his poetry — and when he did take his music to the stage, with tours between 2006 and 2009 that saw his band play in Israel, Europe, and across the United States, the frontman for indie rockers Silver Jews found plenty of fans along the way. And well before that, Berman’s songs — full of black humor, wry observations, and some real pain — had spawned a devoted cult following.

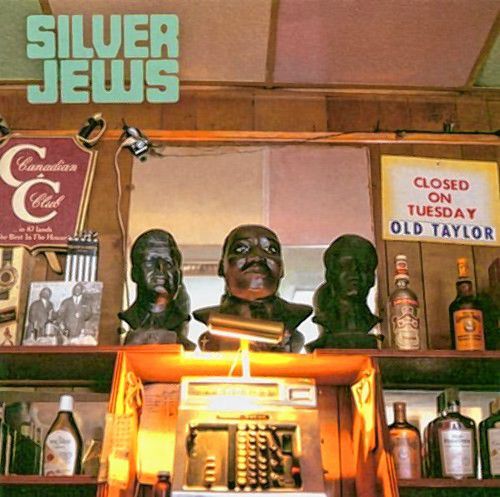

People who got to know Berman when he touched down in the Valley in the 1990s, where he recorded one of his albums and studied in the MFA Program for Poets & Writers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, were not surprised by his success as a musician. “He was a true artist,” says guitarist Peyton Pinkerton, who played on the 1996 Silver Jews album “The Natural Bridge,” recorded in Connecticut, and on the band’s tours of 2006-09. “Just a great songwriter, with an acute sense of observation.”

And poet and writer Dara Wier, a longtime professor in the MFA writers’ program at UMass, recalls Berman as “such a real genius — that’s not an overstatement.” Wier, who worked with Berman on his UMass thesis, says her late husband, UMass professor and poet James Tate, was also a huge fan of Berman’s poems and his songs: “We were lucky enough to see them fresh out of the gate, so to speak.”

More importantly, Peyton, Wier and other friends and admirers say Berman, who was 52 when he died in Brooklyn, N.Y. on Aug. 8, was a funny, generous guy and a good friend who maintained the ties he’d made with different people over the years, even as he went through periods of depression and substance abuse.

“He would send me these funny little gifts, like boxes of Mike and Ike [candy],” says Pinkerton, who lives in Holyoke and previously played with New Radiant Storm King, the Pernice Brothers and other area bands. “We were texting and emailing on a regular basis. I got a text 12 hours before he died. He sent me this grainy photo — he would only use an old flip phone — of this, I guess you’d call it, Adult Entertainment club he’d come across in Brooklyn that was called ‘Peyton’s Play Pen.’ It was hilarious.”

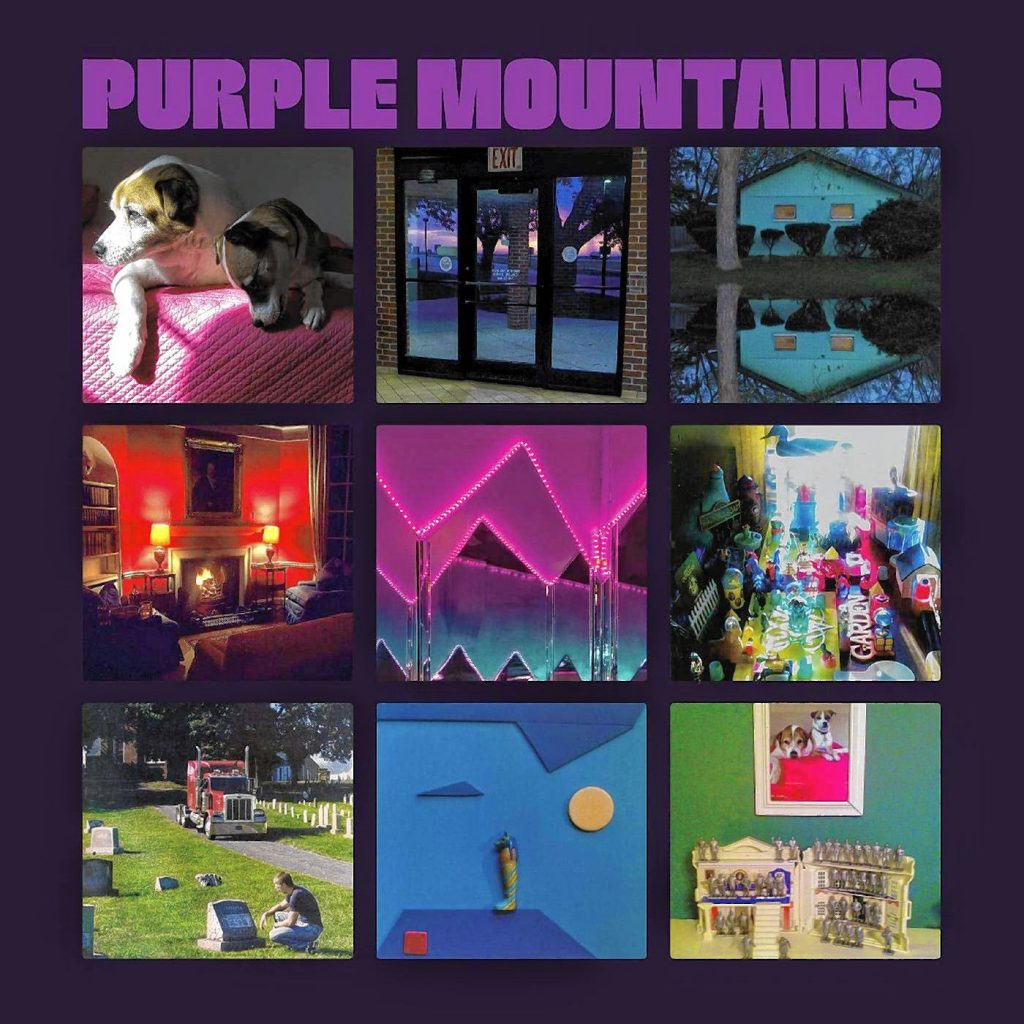

Berman, who had lived in Nashville, Tennessee, for much of the past two decades before moving to Chicago earlier this year, had withdrawn from the music scene about 10 years ago following his tours with Silver Jews. But he’d sparked much renewed interest this summer when he came out with a new album, “Purple Mountains,” recorded with members of Woods, a New York folk-rock band. The album received good initial reviews, and Berman and the band were set to begin a six-week tour in August — until he hanged himself just two days before the trip was to begin.

Berman’s death sent shock waves through the music and pop culture world. Any number of major publications — Spin, Rolling Stone, The New Yorker, Pitchfork, Slate, The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Atlantic — wrote obituaries, with tributes to his songwriting and poetry. “Berman had a knack for representing what was right in front of you in a way that made you see it as if for the first time,” wrote Pitchfork. The New Yorker put it like this: “He had a gift for articulating profound loneliness in ways that felt deeply familiar, which in turn made you feel less alone.”

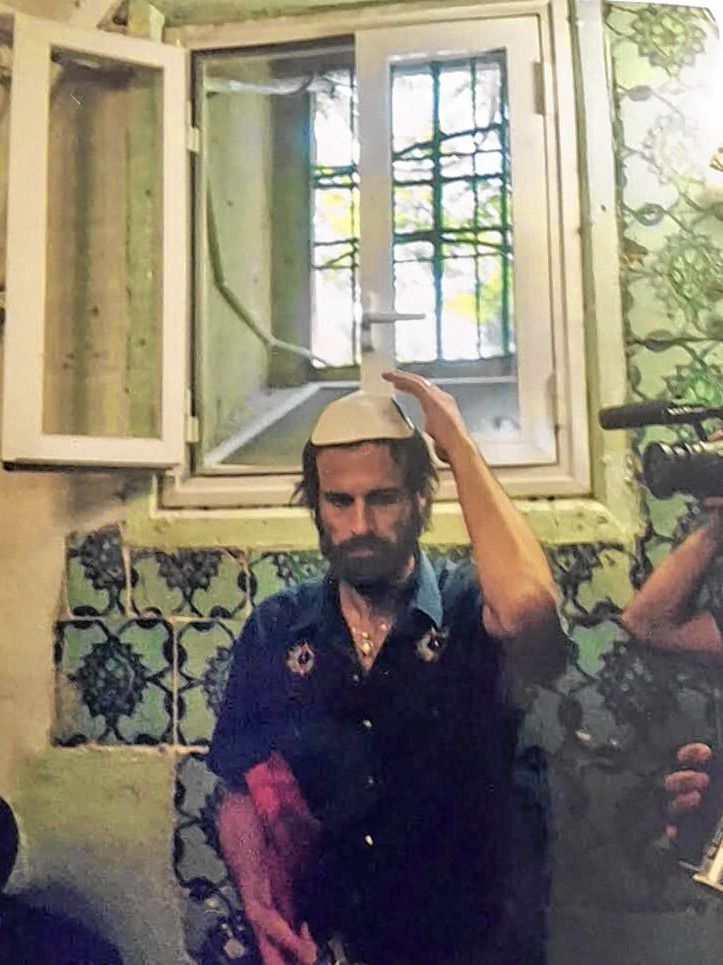

Berman in Jerusalem in 2006 during a Silver Jews tour. The singer and songwriter had begun a closer examination of his Judaism at the time.

Needless to say, Berman’s passing has also left friends shocked and saddened. “He was a wonderful friend, and not to have him here now … it’s just a really hard thing to get my head around,” says Pinkerton. He notes that while he long remained in touch with Berman over the years, at times he also tried to give his friend space when he became withdrawn or depressed, such as when he was dissatisfied with his singing after a show.

“He would say ‘There’s nothing more tedious than someone trying to talk you out of your emotions,’” Pinkerton says. “In his mind, he had to find the answers himself … I would try to talk him out of those kinds of moods, but maybe I didn’t do it enough.”

Tom Shea of Northampton was an original member of The Scud Mountain Boys, the Valley alt-country band of the early 1990s that included songwriter and singer Joe Pernice, who at the time was also in the UMass writers program and became friends with Berman. Shea says he didn’t know Berman that well, though he and the other Scud Mountain Boys once backed up Berman on some of the latter’s songs, in a local recording session that ultimately did not lead to a record. (Berman also wrote the liner notes to an early Scuds Mountain Boys album.)

Still, says Shea, Berman was about the same age as him, Pernice and several other Valley musicians who knew him at the time “and so that’s kind of scary — to hear that someone of our age is gone, just like that.”

And Pernice, who declined to speak with the Advocate, posted on Twitter when news of Berman’s death broke: “Just heard from Peyton Pinkerton. I wish it was a sick joke. Our friend David Berman has committed suicide. Devastated beyond words.”

But the month following Berman’s death has given friends and acquaintances in the Valley a little space and time to look back with fondness and appreciation for him, both as a person and writer. Pinkerton says it will likely never be known whether Berman’s suicide was something he’d been building to — he’d also attempted to kill himself in the early 2000s — or just something he did abruptly after waking up that day.

But he recalls from touring with Berman that his friend felt “like he’d seen all there was to see, that he’d done all he wanted to do, and he was OK if that was all there would be … He’d made a string of great albums, he’d had his poetry published, he’d been married to someone [his wife, Cassie] who was really good for him. Maybe he felt that was enough.”

Berman, who was born in Virginia and raised partly in Texas, certainly had an interesting life story. While attending the University of Virginia, in Charlottesville, he became friends with and began recording music with Stephen Malkmus and Bob Nastanovich, who would go on to become the nucleus of the indie rock band Pavement, though the two also served as early members of Silver Jews (Silver Jews, over the years, was essentially Berman and whoever he recorded with at the time).

At UMass, Berman met Joe Pernice as well as a number of other Valley musicians such as Pinkerton, Matt Hunter (another member of New Radiant Storm King) and Zeke Fiddler (Berman’s roommate in a Northampton apartment). He also got to know other writers in the area, and he impressed the students he had as a teaching assistant, or who heard his poetry at a reading.

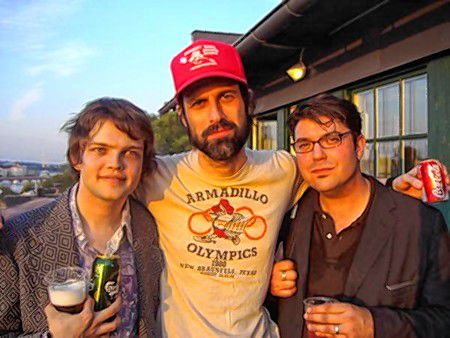

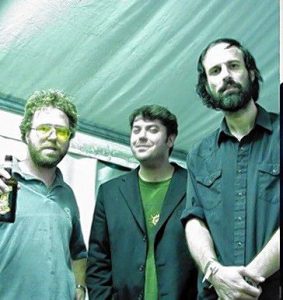

Peyton Pinkerton, center, with David Berman, at right, and Steve West in Wales in 2006 when Pinkerton and West backed up Berman on a tour of Silver Jews.

Sarah Larson, a 1995 UMass alumna who now writes about pop music and culture for The New Yorker, told the Advocate that she met Berman through Pernice, who became a good friend of hers. Though she didn’t know Berman well, she admired his poetry and later his music: As she wrote in The New Yorker last month, “If you took a junior-year creative-writing class [at UMass] in the spring of 1994, you had a good chance of being taught by a future musical heavyweight: Berman, or, in my case, Joe Pernice. Berman was a figure of admiration and mystique — tall and handsome, with the aura of a low-key oracle. Many of us loved his poetry but hadn’t heard his music yet.”

Dara Wier, the UMass professor, recalls that her late husband — James Tate, a winner of both a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award for poetry, died in 2015 — liked a line from one of Berman’s poems, “Classic Water,” so much that he used it as the title of one of own last poems, “The Government Lake.”

“[James and I] used to talk about David and his out of this world poems often,” Wier wrote in a follow-up email. “We will always think of David as a gift to poetry. In words and in music, he brought new life to everything he touched.” (Berman’s first volume of poetry, “Actual Air,” was published in 1999.)

Wier also recalls that Berman made a special effort to stay in touch with her after her husband died, just to check in to see how she was doing: “He was so thoughtful that way.”

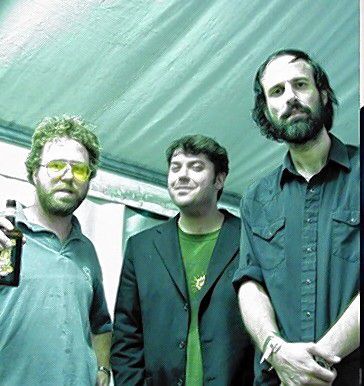

David Berman, center, with Peyton Pinkerton, at right, and William Tyler in Sweden in 2006 during a Silver Jews tour.

And poet Peter Gizzi, who also teaches in the MFA writers program at UMass, remembers Berman coming back to give a reading at the university in 2002. “It was wonderful. I enjoyed meeting him,” he said in an email. “I liked his offbeat way. I am a fan of his poetry…. It is a deeply sad loss.”

Berman went through some dark times later in his life: substance abuse, depression, a suicide attempt in 2003, and a very public break in 2009 with his father, Richard Berman, a longtime public relations executive and lobbyist for clients like tobacco companies. His son called him “evil” and said at the time that he was stepping away from music to find some way to undo the damage of his father’s work. And in the last year or so, Berman had separated from his wife — though they evidently remained on good terms — and had seemed to become increasingly isolated.

But Pinkerton remembers Berman as a guy “who really could be the life of the party,” a raconteur with a droll sense of humor who could talk knowledgeably about a lot of different subjects. On the other hand, he wasn’t someone who would whip out a guitar at a party and sing for people: “He didn’t like playing guitar. He really just wanted to be a singer, but he was insecure about his voice — he always felt he needed to have his voice fixed.”

Yet many found Berman’s largely flat, deadpan vocals a good match for the generally spare melodies of his songs (“His voice is a distinctive instrument” Spin magazine once wrote) and their off-beat subjects. His music might variously be called indie rock, roots/country rock, or lo-fi; it’s built mostly around basic chords and strummed guitars, with straightforward drumming and bass and minimal soloing (Berman’s wife played bass and sang on some of the later albums, which had some more production polish).

The real thrust is the lyrics: rambles across history and nature and the wide expanse of America, with genuine personal darkness and melancholy leavened with some dark humor.

Take the opening lines to “Punks in the Beerlight,” a tale of excess and lost love from “Tanglewood Numbers,” the 2008 Silver Jews album: “Where’s the paper bag that holds the liquor? / Just in case I feel the need to puke.” Or consider the line from “Inside the Golden Days of Missing You,” from “The Natural Bridge,” the album Berman recorded with Pinkerton and other Valley musicians in 1996: “I wish they didn’t set mirrors behind a bar / ‘cause I can’t stand to look at my face when I don’t know where you are.”

Pinkerton says one of his favorite Berman songs is “Pretty Eyes,” also from “The Natural Bridge,” which Berman recorded mostly just playing an acoustic guitar, with Pinkerton and the other band members coming in during the song’s final stages. He sees it as a symbol of sorts for the way Berman overcame his struggles in recording the album, as his friend was plagued with doubts about his singing and how the project was — or wasn’t — coming together.

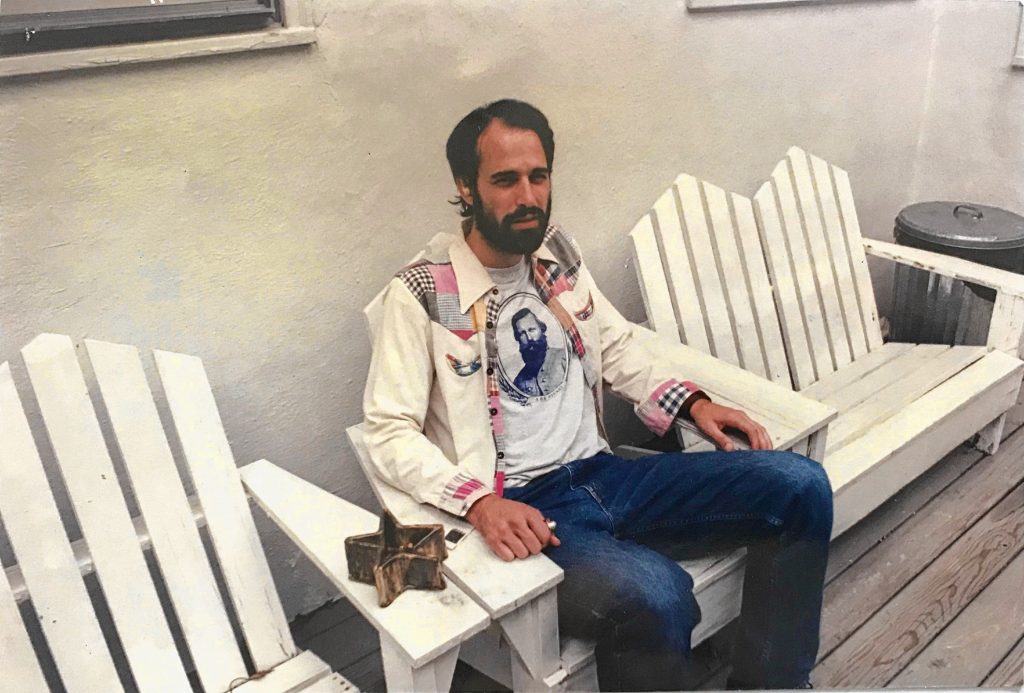

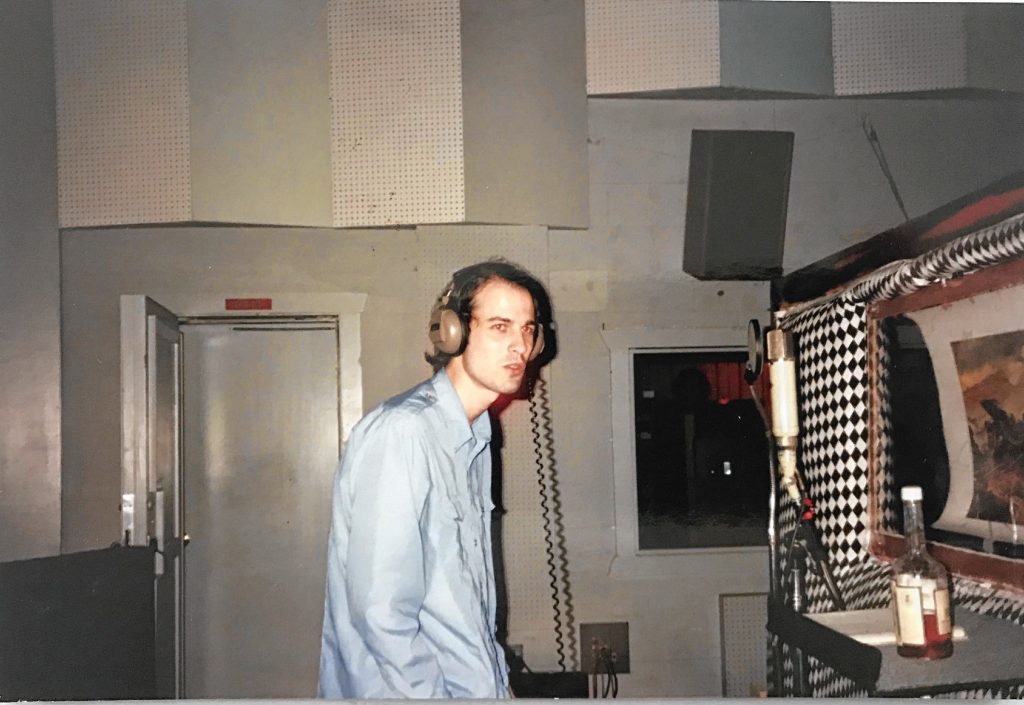

Drag City, the Chicago record label that issued David Berman’s albums, posted this photo of the singer, in Chicago, after his death in August.

“He was staying in my apartment in Northampton [while we worked on the album], and he wasn’t sleeping — I could hear him up night after night,” recalls Pinkerton, who adds that Berman finally went to the hospital one night to get some sedatives. “I didn’t know if the album was going to get made, but in the end he did it — we did it.”

It’s hard to look at the songs from Berman’s last album, “Purple Mountains,” and not see him essentially writing a farewell note. Titles like “All My Happiness is Gone” and “Darkness and Cold” seem to speak for themselves. The latter song, in which he sings “The light of my life is going out tonight / With someone she just met / The light of my life is going out tonight/ Without a flicker of regret” has an accompanying video in which a morose-looking Berman watches as his ex-wife, Cassie, puts on makeup, high heels, and fresh clothes as she readies for a date.

But Wier, for one, prefers to remember the former student and friend she called “a beautiful person,” and to think about the 200-odd people, including herself and Pinkerton, who came to Berman’s memorial service in mid-August at a synagogue outside Nashville. “There were so many friends, from so many walks of life, and they all told stories about David … He touched the lives of so many people.”

“It’s so sad not to have him here anymore,” Wier added.

But she also recalled the time a few years back when she came to Nashville to do a reading of some of her new poems and spent three days with Berman and his wife. Berman “was so sweet, showing me all around the city, and he and Cassie really took care of me. It was a wonderful time. I’ll always have that memory of him.”

Self-Portrait at 28 – By David Berman

I know it’s a bad title

but I’m giving it to myself as a gift

on a day nearly canceled by sunlight

when the entire hill is approaching

the ideal of Virginia

brochured with goldenrod and loblolly

and I think “at least I have not woken up

with a bloody knife in my hand”

by then having absently wandered

one hundred yards from the house

while still seated in this chair

with my eyes closed.

It is a certain hill

the one I imagine when I hear the word “hill”

and if the apocalypse turns out

to be a world-wide nervous breakdown

if our five billion minds collapse at once

well I’d call that a surprise ending

and this hill would still be beautiful

a place I wouldn’t mind dying

alone or with you.

To read the full poem, visit https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/self-portrait-at-28/

Steve Pfarrer can be reached at spfarrer@valleyadvocate.com.