Two Latinx plays in the area revolve around themes of dislocation — displaced neighborhoods, populations, and minds. Quixote Nuevo, at Hartford Stage, transplants Cervantes’ demented knight errant to a Texas border town, and Not for Sale, in Holyoke, puts the gente in gentrification.

MIFA, the Massachusetts International Festival of the Arts, is a Holyoke-based venture that’s working to restore the city’s venerable Victory Theatre as a regional performance venue while also forging partnerships with the Latinx community. MIFA and the community-action organization Nueva Esperanza have co-sponsored several shows at the storefront performance space El Mercado.

Last year they brought New York’s Pregones theater with Dancing in My Cockroach Killers, by local artist/activist (and newly appointed poet laureate of Springfield) Magdalena Gómez. And the previous year saw UrbanTheater of Chicago’s satirical La Gringa. Now UrbanTheater is back with Not for Sale.

Guadalís Del Carmen’s dramedy, “performed in English with sprinkles of Spanish,” takes place in Chicago’s Humboldt Park, the city’s long-established Puerto Rican neighborhood, now battling encroachment by the forces of gentrification. Her characters include a shopkeeper struggling to pay his property taxes, a realtor who may or may not have the community’s best interests at heart, a local politician trying to balance the demands of longtime residents and entitled newcomers, and young activists with more passion than strategy.

Guadalís Del Carmen’s dramedy, “performed in English with sprinkles of Spanish,” takes place in Chicago’s Humboldt Park, the city’s long-established Puerto Rican neighborhood, now battling encroachment by the forces of gentrification. Her characters include a shopkeeper struggling to pay his property taxes, a realtor who may or may not have the community’s best interests at heart, a local politician trying to balance the demands of longtime residents and entitled newcomers, and young activists with more passion than strategy.

“We think it’s important to make sure people are able to see the best of this kind of theater,” Donald Sanders, MIFA’s head, told me — “professional companies with a strong history and point of view, working through these feelings and emotions on the highest level of artistry.”

He said performances at the tiny El Mercado are “site-specific in a certain way. It’s such a congenial space, and the theater piece itself feels organic because it puts the audience into the environment.”

Oct. 18-20, El Mercado, 413 Main Street, Holyoke. Tickets & info here.

Quixote Nuevo

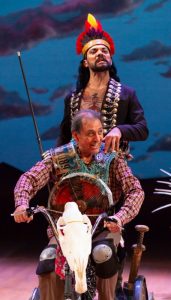

At the beginning of Octavio Solis’s buoyant take on Don Quixote, set in a fictional West Texas town on the border with Mexico, José Quijano, a former literature professor now slipping into dementia, is being shoehorned into an assisted living facility. Suddenly, he’s surrounded by dancing, taunting trickster spirits from Mexican folklore and stalked by a smirking specter of death. He makes a dash for freedom astride “Rocinante,” a three-wheeled bike decked out with a horse’s skull. He’s armored in repurposed car parts and a bedpan helmet, brandishing a pool-cue lance.

Pursued by his long-suffering sister and adoring niece, along with a priest and social worker, he sets out on a chivalric quest, vowing to fight for “the unemployed, the uninsured, the undocumented,” and to find his long-lost love, Dulcinea. Along the way, he recruits Manny, the dim but affable proprietor of a pedal-powered ice cream cart, to be his Sancho Panza.

The show, a co-production with theaters in Boston and Houston, plays at Hartford Stage through October 13. It boasts an all-Latinx cast and a Latina director, KJ Sanchez. Takeshi Kata’s bare, expansive stage evokes the southwestern desert’s arid vastness and endless sky. An ensemble of seven take on multiple roles, from the boozy regulars in a roadside cantina — the “castle” where the deluded Don is mockingly knighted — to a huddled band of migrant workers camping in a desert canyon.

The mood is lively and colorful (Rachel Healy’s costumes are gorgeous), the style broad, rich with slapstick and caricature. The dialogue, now lyrical, now earthy, is salted with Spanish and Spanglish, and David R. Molina’s original music and songs give the piece the air of a street festival. In fact, the production seems a little constricted in the Hartford theater’s formal interior, and probably breathed more fully at its outdoor premiere last year, with some of the same cast, at the California Shakespeare Theater.

The mood is lively and colorful (Rachel Healy’s costumes are gorgeous), the style broad, rich with slapstick and caricature. The dialogue, now lyrical, now earthy, is salted with Spanish and Spanglish, and David R. Molina’s original music and songs give the piece the air of a street festival. In fact, the production seems a little constricted in the Hartford theater’s formal interior, and probably breathed more fully at its outdoor premiere last year, with some of the same cast, at the California Shakespeare Theater.

Octavio Solis is an El Paso native, and Quixote Nuevo explicitly evokes the current border crisis. The Wall plays both a physical and symbolic role here. When one character refers to it as plastered with “ads for Mar a Lago,” the knight asks, “Is that an evil enchanter?” The answer: “Close enough!”

The picaresque journey suggests other walls as well, separating past from present, fact from fantasy, hope from deliverance. Some of the episodes parallel those in Cervantes’ classic tale — instead of a windmill, the “giant” our hero vanquishes is a border patrol surveillance balloon. Other moments flash back to a younger Quijano and his love for Dulcinea, a Mexican girl from across the Rio Grande — a Romeo and Juliet separated not by feuding families but by the hostile border.

Emilio Delgado (he was Sesame Street‘s beloved handyman Luis) is a marvelous Quijano, finding humor in the viejo’s heroics and pathos in his foibles. Juan Manuel Amador is an amusing Manny/Sancho, at first the pragmatic foil to the Don’s flights of fantasy but gradually seduced by the reckless adventure.

In the versatile ensemble, I particularly enjoyed Hugo E. Carbajal as the sometimes impatient grim reaper, Gisela Chípe as both the old man’s brisk social worker and the young man’s dewy Dulcinea, and Orlando Arriaga as a refugee whose family fled gang violence at home, only to suffer the same and worse in the unwelcoming North.

That heartwrenching monologue doesn’t invalidate the antic spirit that animates the play, but puts it in perspective. We rejoice at “this old dreamer’s heart,” even as we wonder: Is the dream impossible after all?

The Stagestruck archive is at valleyadvocate.com/author/chris-rohmann

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email Stagestruck@crocker.com