Bassist Avery Sharpe has been playing and composing music for years, touring and recording with jazz greats like McCoy Tyner, Dizzy Gillespie, Wynton Marsalis, Yusef Lateef, and Billy Taylor. As a composer, he’s written music not just for his own ensemble but for a wide range of other artists, in multiple settings: the Springfield Symphony Orchestra, the Connecticut-based classical group Fidelio, and a long-running stage production about the Harlem Renaissance, “Raisin’ Cane.”

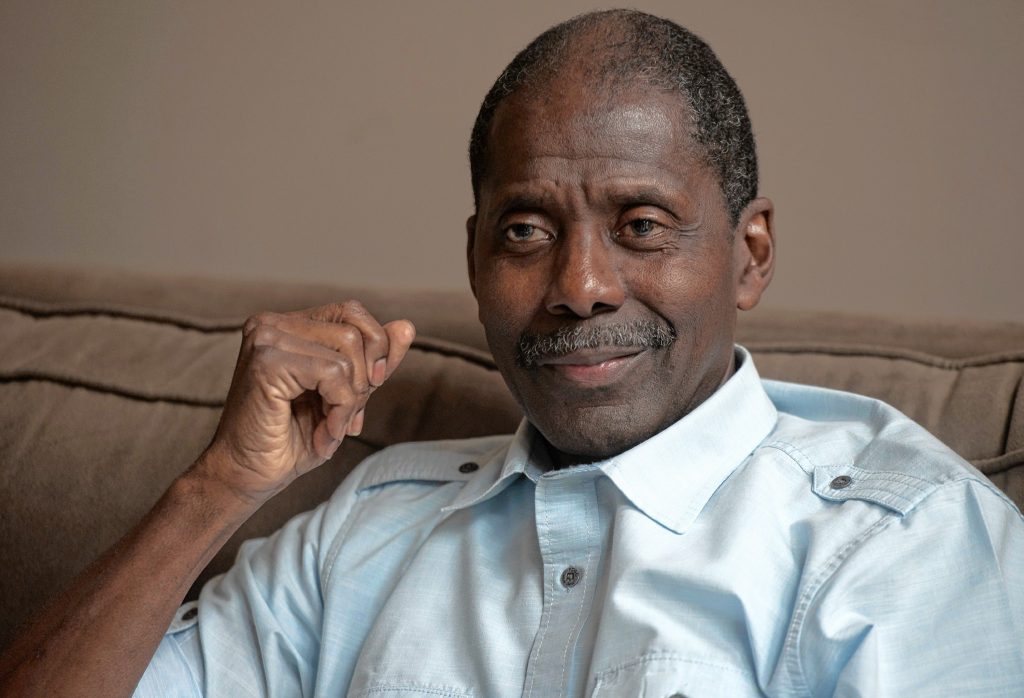

Sharpe, seen here in Plainfield home, is an acclaimed bassist who has played and recorded with a host of jazz legends, from McCoy Tyner to Wynton Marsalis. Carol Lollis photo

Much of that has been music with a purpose. Sharpe has written pieces inspired by the stories of a number of noted African American figures, from the abolitionist Sojourner Truth to 1936 U.S. Olympic star runner Jesse Owens to Primus Mason, the 19th-century Springfield philanthropist and real estate developer who became a success after escaping indentured servitude in Connecticut.

But when Sharpe, a University of Massachusetts Amherst graduate who has deep connections to the Valley, ran into a friend from Amherst, doctor and visual artist Shirley Jackson Whitaker, at Whole Foods in Hadley a couple years ago, he was stumped at first when she said to him, “2019 is coming — what do you think?”

“I was like, ‘OK, so?’” Sharpe said during a recent interview is his home, tucked away in the quiet fields and woods of Plainfield.

“But then it hit me,” he added, “and [Whitaker] was saying ‘You’re not listening to me,’ and I said, ‘No, I’m starting to hear music now.’”

Avery Sharpe, here in his home in Plainfield, has composed a new album, “400,” that marks the infamous anniversary of the introduction of slavery into the future United States. Carol Lollis photo

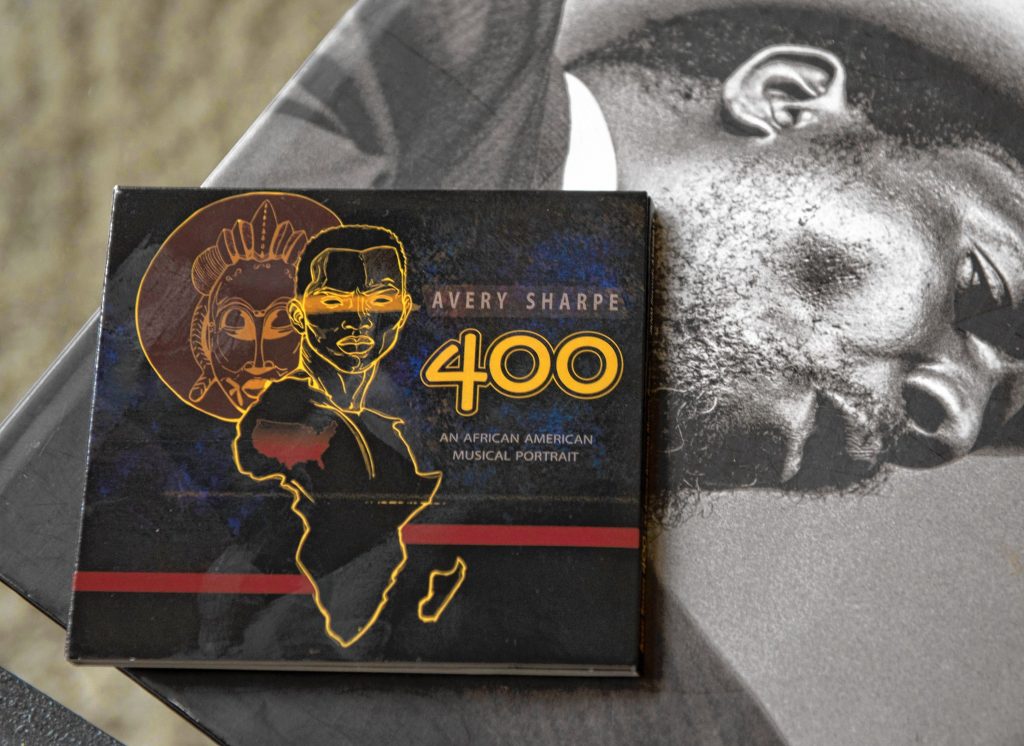

That music is now part of Sharpe’s most recent album, “400: An African American Musical Portrait,” an epic project whose title is drawn from a now-infamous anniversary: It was in 1619 that African slaves, seized by English pirates from a Portuguese slaving ship in the Gulf of Mexico and sold to English colonists in Hampton, Virginia, were first introduced to what was to become the United States.

“When black folk hear ‘2019,’ they understand it in reference to that anniversary,” Sharpe said. “It took me a moment, but when I had that conversation [with Whitaker], I was suddenly hearing all this music and I was thinking, ‘How do I document this?’”

Valley audiences will get a chance later this month to see how the acclaimed bassist did that, as Sharpe will bring his sextet — piano, bass, guitar, drums, trumpet, and tenor saxophone — to Bowker Auditorium at the UMass Fine Arts Center on Nov. 21 at 7:30 p.m. to play “400” in its entirety. Joining him and the other musicians will be what he calls the “Extended Family Choir,” a six-member group that includes his brother, sister, niece and nephew.

The new album is a sweeping and sometimes complex musical journey that incorporates elements of spirituals, gospel, blues, plantation music, ragtime, and other idioms — including classical music and a touch of rap — all of it filtered through a prism of modern jazz. Emotionally, the music can switch from somber, gentle passages that convey pain and isolation to more powerful, inspirational moments, such as when a choral arrangement of a civil rights era anthem segues into a spoken-word rap about black pride.

On his new album “400,” bassist and composer Avery Sharpe charts the musical journey of African Americans over the past four centuries. Carol Lollis photo

As he looks back on the album, recorded last fall primarily in West Springfield, Sharpe says his biggest challenge in composing the music was the sheer scope of the project. “The hardest part was to try and condense 400 years into 60 minutes [of music],” he noted.

At the same time, his past experience in composing a wide range of sounds, especially for pieces that were thematically inspired by chapters or figures from African American history, gave him the confidence to proceed.

“I wouldn’t say this was easy, but it was the culmination of all the things that I’d been doing,” he noted. “I’m kind of known as the history guy now, so in a sense I was kind of building toward this — I felt like I knew the ground pretty well.”

He has broken the 400-year period the music covers into four, 100-year increments, each of which has two or three separate compositions. The first section, for instance, chronicling 1619 to 1719, includes two choral-dominated pieces, “Arrival” and “Is There a Way Home.” Both explore the shock, terror and sadness of Africans violently taken from their homes and forced into a hellish journey across the Atlantic to a strange new world.

“Arrival,” for instance, is a spiritual-based number, underpinned by guitar, saxophone and energetic drumming, that’s sung in Swahili, while in “Is There a Way Home,” the singers pose questions of what they might find in this new land, based on what they’ve heard from other captives; their continued refrain is “That’s what they tell me in Africa.” An almost brooding flute, played by saxophonist Don Braden, floats above the voices, and a djembe, a West African drum, is also part of the composition.

Sharpe is an acclaimed bassist who has played and recorded with a host of jazz legends, from McCoy Tyner to Wynton Marsalis. Carol Lollis photo

“There’s that natural thought, when the Africans arrive, of ‘How’d I get here?’ and ‘Can I get back to where I came from?’ ” said Sharpe.

The next 100-year interval, from 1719 to 1819, covers what Sharpe calls the Colonial Period, with two distinct compositions: one built primarily on piano and some rapid-fire soloing by Kevin Eubanks on acoustic guitar, and another piece, “Fiddler,” that includes both a “quasi-classical” section with violins and piano and one with a faster, more homespun touch on fiddle.

The connection, says Sharpe, is that when slaves played fiddle, they might be called to do so for their master’s social occasions and dances — as the protagonist in the 2013 film “12 Years a Slave” had to do — or they might do so for themselves. “That’s what you’d call a plantation song, the music that slaves developed on their own,” he notes.

The music on “400” broadens over the final two 100-year sections, incorporating post-Civil War black spirituals, ragtime and other early jazz — the New Orleans sound — and the more modern blues and jazz of the 20th century. Part of the theme for the latter section is based on something Sharpe, who was born in Georgia but raised partly in upstate New York and in Springfield, says affected his family: the slap African American men felt after serving their country in the military during the two world wars, only to come home to continued second-class citizenship.

His father, who served in both World War II and the Korean War, had that same experience, Sharpe said. “He had hoped things would be different [when he came back],” he said.

But this later music also finds inspiration in the artistic achievements of the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. The Extended Family Choir, led by Sharpe’s brother, Springfield-based musician Kevin Sharpe, offers an arrangement of the gospel freedom song “Ain’t Nobody Gonna Turn Me Round.” Avery Sharpe’s niece, Sophia Rivera, then tacks on an original rap to that piece that succinctly encapsulates the long struggle for racial justice, including the unforgettable line “And yes the Civil War was about slavery / No matter what your Daughters of the Confederacy textbook says.”

Avery Sharpe’s new album, “400,” is one of a number of extended compositions he’s written to commemorate significant events and figures in African American history.

“[Sophia] is a visual artist as well as a singer, and she’s started to become a little radical, so I said ‘Why don’t you write me a spoken-word piece?’ ” Sharpe said with a chuckle. “And she really delivered.”

The last section of “400” is called “500” and looks past Barack Obama’s presidency to the next century with a jazzy, modern turn that, as one reviewer puts it, “points beyond the album’s historical trajectory, both musically and politically, and makes clear that the African American story, like that of jazz itself, is a narrative that is very much still unfolding.”

The Extended Family Choir — members have performed previously on some of Sharpe’s album — will join Avery Sharpe and his ensemble at the Nov. 21 concert at Bowker Auditorium at UMass Amherst. For tickets and more information, visit fac.umass.edu/online/ and go to the calendar listings for Nov. 21.

Steve Pfarrer can be reached at spfarrer@valleyadvocate.com.