The Conway Sportsman’s Club lies at the dead end of a quarter mile dirt driveway, a small cabin of a building flanked by a panoramic wooded hillside containing several shooting ranges, whose ridgeline separates the South and Bear River watersheds. At a shaded table under the overhang of the cabin’s wraparound porch sits club secretary and firearms safety instructor Ken Ouimette, holding an assault rifle, waiting to greet me.

“This is one of the bad ones,” he says, placing the firearm on the table in front of him.

It feels like a loaded statement. On one hand, assault rifles are banned in the state of Massachusetts, Ouimette explains. Only police officers can use them. They are often carried in cruisers. On the other hand, I am a reporter writing a story about guns at a time when mass shooting events and other gun crimes are often lead news stories.

Ouimette is a lifelong hunter as well as the town’s chief of police, where he’s been on the force since 1990. He sometimes cleans and sights in a new rifle at the club before it is used by one of his officers.

He lays out several other guns he has brought with him — a double-barrel rifle, a couple of six-shooter pistols, and another handgun that loads the magazine up into the pistol grip — so that I can compare their weights and become more familiar with them.

“We need to take the whole mystique away from it,” says Ouimette. Whether for shooting or for self-defense, “operating a firearm is a learned skill.”

Firearms, continues Ouimette, “should be an education and safety issue,” like drugs or sex ed.

Admittedly, I know little about guns and have had little contact with them. A few years ago I fired a .22 at a ranch while on a family vacation over the 4th of July. That was the first time I had fired a gun since taking riflery as a kid at a day camp in the Boston suburbs. I do have a few friends who shoot or hunt, and I am always appreciative when they share their grouse or venison.

Ken Ouimette, the Conway police chief, poses with a AR-15 Patrol Rifle at the Conway Sportsman Club. Carol Lollis photo

It is a hot, sunny day, and the porch provides a pleasant place to sit. We talk for a half hour or more, during which only one car makes its way up the long, dirt drive. The driver, upon realizing his mistaken direction, turns his car around and heads away from the club.

“You can’t make guns disappear,” Ouimette says. “There’s too many of them.”

Then he suggests we shoot some clays. So we head up toward one of the clay station shooting ranges hidden on the forested hillside.

It was at this point that irrational fears began to show up. How exactly did I find myself walking up a dirt trail next to a stranger who claimed to be a police officer and was holding a double barrel shotgun and several rounds of ammunition? How did I get into this predicament? What if things suddenly took a turn for the worse?

Which was interesting, if not instructive, because various fears — or at least cautions — routinely came up during my reporting on this story: fears of guns, fears of another mass shooting, fears of not being able to protect yourself against an attacker, fears of a tyrannical police state, fears of being misrepresented in the media.

This is an article about guns and the Valley’s firearms community that intends to be apolitical, while recognizing that one of the few things most firearms owners and gun control advocates would agree on is that the contentious and often divisive culture war commonly called “the gun issue” is an inherently political one, has been for some time, and is not likely to get resolved any time soon.

A divided dynamic

But why, exactly, is the gun issue such an issue?

Oiumette says that the media, which he believes tends to be anti-gun, drives some of the ongoing debate. “People have been convinced that guns are evil,” he says. “Many gun owners are hesitant to talk with media.”

Oiumette was one of the few firearms advocates who not only agreed to speak with me, but also wanted to further this dialogue toward a better, or at least broader understanding of the issue. Most of the gun store owners and sport club members I reached out to declined to be interviewed.

“People are angry these days, and less tolerant of other people’s views,” Oiumette continues, noting that both gun owners and gun control advocates tend to stay in social circles with those who hold similar mindsets.

This divided dynamic was the starting point for my conversations with various firearms owners in the Valley. Even while acknowledging that not everyone out there holds a polarizing opinion about the gun issue.

“Most firearms owners keep their heads down and their mouths shut,” says Kirk Whatley. The Valley, he says, is largely anti-gun, especially in comparison to New Hampshire and Vermont. “Nobody looks at you with a gun in Vermont.”

Whatley, an independent firearms instructor who began Whatley Training LLC a few years ago, regularly offers his NRA certified and Massachusetts State Police registered training at the Norwottuck Fish and Game gun range in Amherst (see “The Kirk Whatley Challenge: Before you write guns off, fire one, safely,” June 14, 2016), just up the road from Atkins Farms Country Market. He commutes to Keene, New Hampshire, regularly for work.

Firearms owners can easily get ostracized, Whatley continues, and so can their kids. Other parents often hesitate to let their kids play at the home of a friend whose mother or father keeps a firearm in the house. “Still,” says Whatley, “there’s a sizable firearms-owning community here in the Valley.”

Joelene Guzzo “grew up shooting,” and now regularly organizes women who are interested in taking a firearms safety course in order to get a License to Carry. “I like to get people involved,” says Guzzo.

A parent of one of her children’s friends once asked whether she kept “any unsecure firearms on the premises,” she says.

Ouimette says he’s known a lot of teachers who own guns, but keep it quiet for fear of being shunned by their community.

The Valley has a higher density of gun owners than other parts of New England, continues Oiumette, and many of those owners defy expectations. Ouimette says he knows plenty of doctors and lawyers who own guns. “There is no profile” for either gun owners or for people who are anti-gun, he says.

Still, those stereotypes exist. And those in the firearms community are confronted by them regularly.

Despite misconceptions, says Kency Gilet, gun owners do care about violence committed with a gun. “Whenever something bad happens,” he says, “the whole gun community cringes.”

Gilet is a licensed mental health counselor who this past fall ran an unsuccessful campaign for an at-large seat on the Springfield City Council.

He was not raised with firearms, he says, but became a gun owner after getting married, buying a home, and preparing to start a family of his own.

Gilet calls the NRA “one of the oldest civil rights organizations,” noting that they wanted to distribute firearms to former slaves after the Civil War. He has an NRA sticker on his car, which surprises a lot of people, says Gilet, because he is a person of color.

Movements like Black Guns Matter have done a lot to change the concept of gun ownership, Gilet continues. But he “wishes the urban community felt that the 2nd amendment belonged to them.”

Gilet became a member of the Gun Owners Action League of Massachusetts (GOAL) a few years ago. Last fall he became a board member of GOAL.

Joelene Guzzo, of Wilbraham, holds her AR-15 rifle, Thursday, Jan. 9, 2020 in Florence. Jerrey Roberts photo

Common stereotypes Gilet has heard include all gun owners being gun nuts, who don’t care about children, are weak, and need a gun to feel like a man.

But owning a gun “is humbling,” continues Gilet. It’s not like the movies, or eye-catching headlines.

There is a “glorification of gun violence,” says Guzzo. Gun owners are seen as being “radical. But we’re not. I own a bakery. I’m a mother of three kids.”

Walt Lamon, the owner and operator of Culverine Firearms, in Agawam, says gun owners are treated like “felons in waiting.” He thinks the opposite is true. “As a group,” Lamon says, gun owners “are the most crime free of any in the state. We have to be or we would not [be able to] keep our License To Carry.”

Guzzo agrees. Guns owners, she says, “are the most law-abiding people.”

Many firearms owners reflect Oiumette’s view that part of the problem is the portrayal of them in the media.

“Firearms owners, as a group, are constantly misquoted and misrepresented,” says Whatley.

This media relation, continues Whatley, is really bothersome for most firearms owners.

“It is definitely a consistent and local media wide occurrence,” says Lamon. “There is only one TV station I would agree to interview with. The one person I trust has retired.”

Lamon says his reluctance to talk with the media is due to his having been misquoted in the past. “I’ve been ambushed too many times,” he adds.

Frayed relations

Some time before driving up to the Conway Sportsman’s Club, I headed down to West Springfield to check out Guns, Inc., which bills itself as the “largest gun store in Western Massachusetts.” I had never been in a gun store before, and figured, if I was going to write a story about guns, actually being in a gun store was a good place to start. But my experience there was odd and disappointing.

Prior to my visit, I spoke over the phone with the store manager, let him know when I’d be coming by, and even sent several questions by email to be answered by the store’s owners. When I arrived at the store, he said that my visit was causing them to “freak out,” though he didn’t specify why.

Guns, Inc. includes the “Hot Brass” Indoor Firearm and Bow Range at its store location. Safety range officer Terry Regan, who said he bought his first gun 62 years ago, gave me a tour of the facilities. Regan was the only person I spoke with at Guns, Inc. who seemed comfortable with my presence. That struck me as slightly odd, since several employees seemed to be wearing a sidearm, and I was only armed with the proverbial pen. Then again, maybe what I saw weren’t firearms at all, but Leatherman tools.

A few minutes into my tour of the facilities, a woman who did not introduce herself upon arrival but identified herself as Tiffany Harbridge in answer to my questions, suddenly began shadowing my tour with Regan. She didn’t say much, but was most interested in the questions I was asking Regan, and with the photos I was taking of the store and shooting range.

Shortly after the tour ended, I left. The store owner, whom the store manager had referred to in our emails, did not meet me.

A couple of days after my visit to the store, I received this email from the manager in response to my request to interview the store owner, or at least have her answer a couple of questions via email: “Thanks for coming down to check out the store and range. I regret to inform you that the owners are unable to reply to your inquiries at this time. They simply offered that it was a sporting culture and we simply sell items and rent facility usage to patrons of the sport. I apologize for any inconvenience and we wish you the best.”

Which made me wonder: is the relationship between firearms owners and the media too fractured to make amends? And if it is, how can we have a productive conversation toward achieving a greater understanding around the gun issue going forward?

‘Bad things can happen’

Whether or not they think a better dialogue is even possible, all of the firearms users I spoke with strongly support the 2nd amendment.

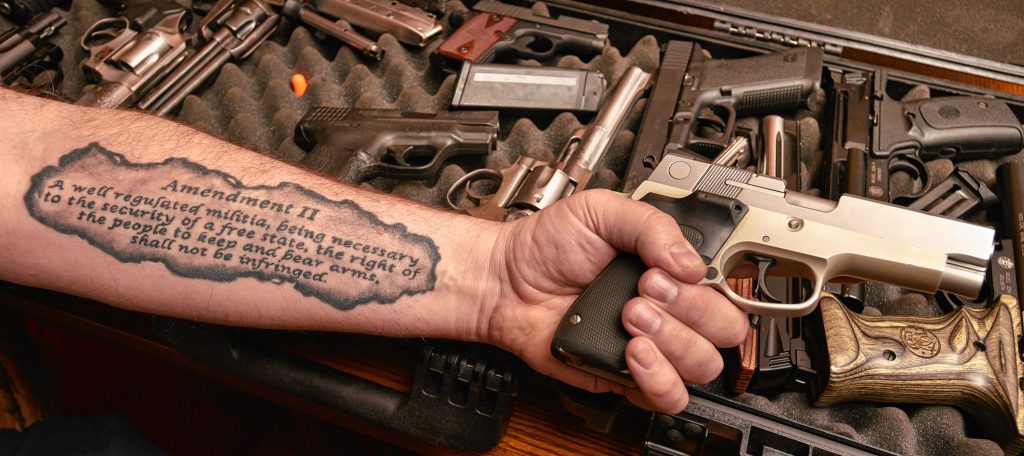

Kirk Whatley displays a box of handguns he uses for his NRA Certified Basic Pistol class at his home in Hadley, Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2019. His forearm bears a tattoo of the Second Amendment to the Constitution. Jerrey Roberts photo

The 2nd amendment is “front and center for firearms owners,” says Whatley, who has a tattoo of the 2nd amendment on his left arm. Protection against the U.S. government is key, he says. “It’s very easy to rule over an unarmed populace.”

Though not raised with firearms, Gilet always understood the 2nd amendment and felt strongly about it, he says.

Using a gun, he says, is first and foremost about personal protection, “which is the purpose of 2nd amendment.”

“Unfortunately,” continues Gilet, “bad things can happen to good people.”

“It can be scary, your home being invaded,” says Gilet. “Most people don’t want to think about that. But good people can commit violent crimes.”

“I pray it never happens to me,” he continues. “Your life is turned upside down if you have to shoot at someone.”

Support for the right of someone to protect themselves, regardless of how unsavory a situation that might be, was consistent amongst the firearms owners I spoke with. So was the notion of an evolving firearms community.

The ascendance of women

The gun industry has been a traditionally male-dominated one, but that is changing, says Whatley. “Women are the largest growing demographic.”

Joelene Guzzo, of Wilbraham, displays an excerpt from the Constitution attached to her AR-15 rifle, Thursday, Jan. 9, 2020 in Florence. Jerrey Roberts photo

“Hunting is a declining sport for a variety of reasons,” says Ouimette. But his firearms training classes have continued to fill up immediately. Over half of those who have signed up for his classes over the past five plus years have been women.

“Hunting numbers are down as the population changes to more urban and less rural,” Lamon says. But there are “substantially more women training for and receiving their [licenses] and buying guns each year.”

Guzzo does not hunt. She does enjoy shooting for sport, however, and goes to a shooting range often. “It’s just fun,” she says, “hitting the target. And the better you get, the more fun it is.”

But self-defense is the primary reason she carries a firearm. “I wouldn’t go anywhere unprotected,” Guzzo says.

“I’m a small business owner in Wilbraham [she owns Theme Cakes By Joelene],” who often works late into the night, continues Guzzo. But having a firearm makes her feel “totally comfortable.”

“So many people are afraid of guns,” she says, “but if you think about it, it’s a great way for women to protect themselves.”

Women are changing the conversation around guns, says Gilet, which, in the era of #MeToo, is “a good response to violence against women.”

“Women,” he continues, “are going to protect the 2nd amendment.”

Gun ownership, Gilet adds, makes a lot of sense for LGBTQ+ community too.

Pink Pistols is an organization “dedicated to the legal, safe, and responsible use of firearms for self-defense of the sexual minority community.” Various chapters “get together at least once a month at local firing ranges to practice shooting, and to acquaint people new to firearms with them,” their website reads.

There are 45 chapters nationwide, including one in Boston. There is no official chapter in the Valley at the time of this writing.

“I don’t know of a chapter in Western Mass,” emailed Aaron Grossman, of the Boston chapter, “though I have talked occasionally to folks who’ve thought about starting one.”

Mental health and violence

Though disagreements abound, both the gun control advocates and firearms advocates I spoke with agree that mental health, and its relation to violence, needs be addressed in more effective way.

Kency Gilet says that suicides committed with a gun should be considered separately from overall deaths caused by a gun.

Most deaths caused by a firearm, says Kirk Whatley, are suicides.

Bishop Doug Fisher, a prominent local gun control activist, agrees. Mass shootings may get more attention, he says, but using a gun to commit suicide is “a bigger, more common problem.”

So what can those in the mental health field do to curb violence committed with a gun? Gilet, a licensed mental health counselor, says there are no easy answers.

“We need to be careful regarding guns and mental health,” says Gilet. “We can’t ban all people who are seeing a therapist from owning a gun.”

The vast majority of people seeing a therapist aren’t violent, Gilet continues. Many see a therapist briefly after suffering a death in the family or experiencing a traumatic event in their lives.

“The mental health field is poor at predicting violence and suicide,” he says.

The importance of language

Last year, Kency Gilet participated in a forum between firearms owners and gun control advocates. It was a productive experience, he says, even though the entire first half of the forum was spent just establishing usable language so that the attendees could have a useful conversation.

I ran into a similar challenge in reporting on and writing this story. Terms such as gun, firearm, gun control, gun violence, violence with a gun, and so forth, which seem to appear intermittently in news stories and whose significance matters little to many, often matter a great deal to firearms owners and advocates against gun violence.

“We want to shift the conversation from a 2nd amendment conversation to a public health conversation,” Ruth Zakarin says. “We can all hold that shared desire.”

Zakarin is the Executive Director of the Massachusetts Coalition to Prevent Gun Violence, a statewide organization that was founded in 2013 — in response to the mass shooting at Sandy Hook — by UMass graduate Angus McQuilken.

The afternoon I was at Guns, Inc., Zakarin was across the river in Springfield, attending a Pioneer Valley Project meeting of over 30 gun control advocates at the office of Bishop Doug Fisher.

Bishop Fisher is the head of the Episcopal Diocese of Western Massachusetts, which serves over 16,000 members in over 50 churches in central Massachusetts, the Valley, and the Berkshires. He is also a gun control activist with Bishops United Against Gun Violence who has attended protests at the headquarters of Smith and Wesson in Springfield. Recently, the Episcopal Church bought 200 shares of American Outdoor Brands, which owns Smith and Wesson, in order to engage in shareholder activism. That holding, Bishop Fisher says, is the minimum amount necessary for shareholder activism.

Bishops United Against Gun Violence, which now includes around 80 members, also began in 2013 in response to the shooting at Sandy Hook. “After that an alarm went off,” Bishop Fisher says. “How did this happen?”

“There wasn’t the same outcry when Columbine happened,” he continues. “It was seen as an outlier. More mass shootings have drawn more attention to the issue.”

But the issue goes further than highly publicized incidents, he says. The “Unholy Trinity” of poverty, racism, and guns, continues Bishop Fisher, creates a “volatile mix of gun violence.”

Bishop Fisher agrees that language is important. “We don’t want to demonize hunting or gun use in general. We view the issue as a public health crisis,” he says. “We’re out to prevent gun violence.”

Bishops United Against Gun Violence has been working with Canticle Communications to develop language to more effectively communicate with both gun owners and the media. Though they have yet to reach out organizationally to collaborate with gun owners or 2nd amendment advocates, says Bishop Fisher.

Other than the forum that Gilet attended, no one I spoke with had intentionally reached out to collaborate with an individual or group from the other “side” of the gun debate.

Lamon says he’s never heard of any gun control folks reaching out to firearms advocates in the hope of achieving a better understanding. “Certainly no one did to me.”

In the ongoing debate, says Whatley, firearms owners are reluctant to concede more space than they already have.

Gilet says that most advocates of gun control have good intentions, but they should be experts on gun laws, and usually aren’t.

Lamon also says that he does not have a problem with people who are against guns, so long as they know why.

“We are confronted with a preconceived notion of who we are,” continues Lamon. “We don’t get invited to the dance and we understand that. What would you say is the perception of the NRA?”

The Conway Sportsman’s Club regularly hosts free family days, which offer activities such as archery, fishing, and shooting black powder rifles. “It’s open to the public, open to anybody,” Ouimette says. But he has not intentionally invited families with parents who are gun control activists. Likewise, none have come on their own.