The last few months have brought national attention to Tulsa, Oklahoma, as plans were unveiled to begin digging there in April in suspected mass graves — locations where corpses may have been dumped almost a century ago, after white mobs attacked and burned a black district of the city, leaving as many as 300 African Americans dead (and perhaps 10 to 20 whites).

What’s known as the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre is generally considered the single worst incident of racial violence in U.S. history. The attack on the Greenwood section of Tulsa, home to a prosperous African American community in the segregated city, left over 35 blocks burned to the ground and over 10,000 people — most of them black — homeless.

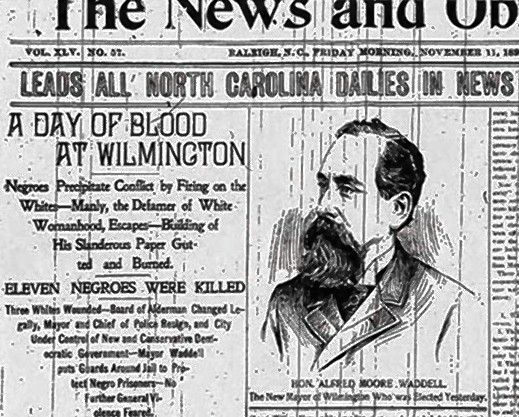

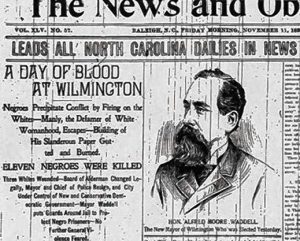

White newspapers in the South blamed the violence in Wilmington on blacks, a lie that remained in place well into the 20th century.

But in his new book, Pulitzer Prize winning author David Zucchino re-examines a white attack on another black community — in Wilmington, North Carolina — that in many ways was far more insidious than the spontaneous outburst of violence in Tulsa.

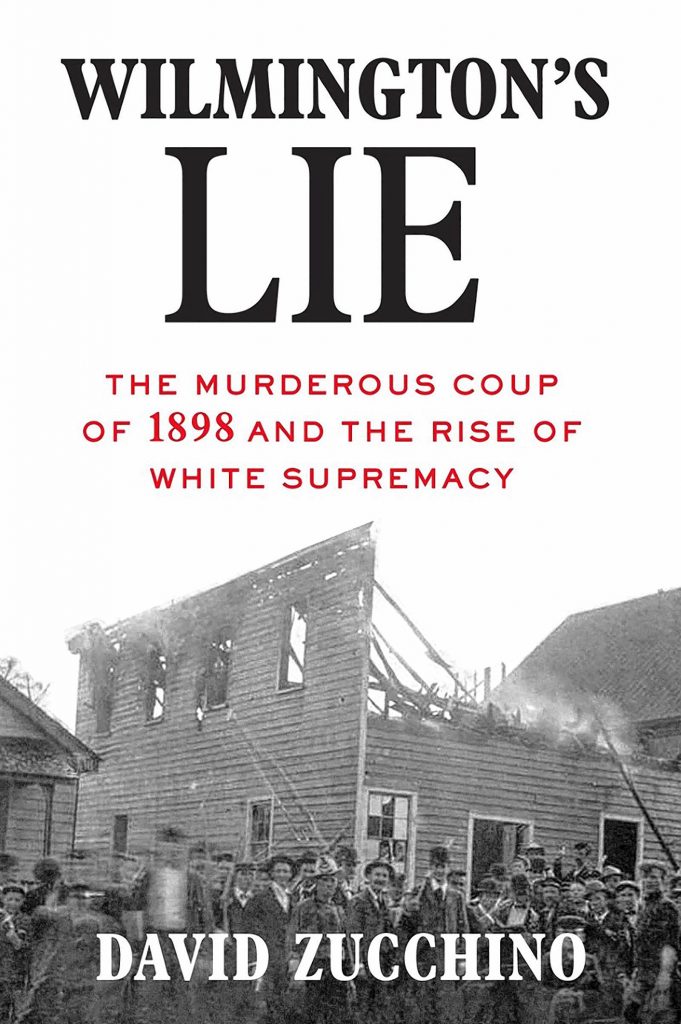

In “Wilmington’s Lie: The Murderous Coup of 1898 and The Rise of White Supremacy,” Zucchino chronicles an openly orchestrated effort by leading white politicians, newspaper publishers, and citizens in North Carolina — almost all Democrats in those days — to take control of the state and of towns like Wilmington that were led by Republicans, who in turn had the vast amount of support from black voters.

In a race-baiting campaign that went on for months, white supremacists declared they would regain the upper hand “by the ballot or bullet or both” and eliminate blacks from public office, especially in Wilmington — and then they did just that, in the process killing at least 60 African Americans, burning homes and businesses and driving hundreds of other blacks from the city forever.

As Zucchino’s searing narrative details, the attack on Wilmington’s black community ushered in decades of white dominance in North Carolina, as voting rights for blacks were stripped away. Other Southern states also used the Wilmington coup as a model for quashing the African American vote and restoring racism as official policy.

And well into the 20th century, the planned violence was portrayed in newspapers and history books as a “race riot,” in which unruly and criminal blacks, ultimately deemed unfit to vote or hold public office, had to be confronted by liberty-loving whites to restore “freedom” and keep the peace.

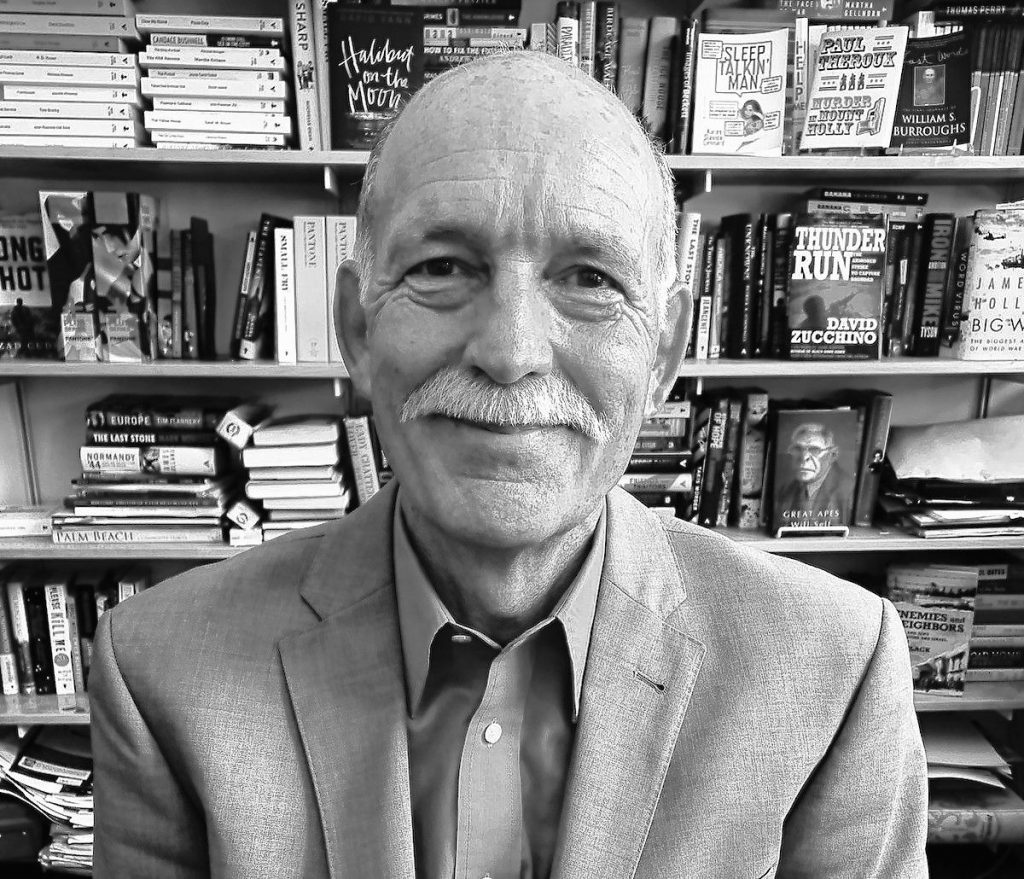

Zucchino, previously a reporter and foreign correspondent for the The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Los Angeles Times and other newspapers, won a Pulitzer Prize for his dispatches from apartheid South Africa. He brings a journalist’s immediacy to “Wilmington’s Lie” while also laying out the historical background for the 1898 terror, as well as the incomplete efforts in the city today to come to terms with this grim past.

His book looks at how, in the advent of Reconstruction after the U.S. Civil War, blacks made some gains in the South, winning the right to vote as well as some elections to state and local offices (and in a few cases to the U.S. House of Representatives). Many of these political gains were rolled back over the next couple of decades, however, as former Confederate leaders took control of the levers of government.

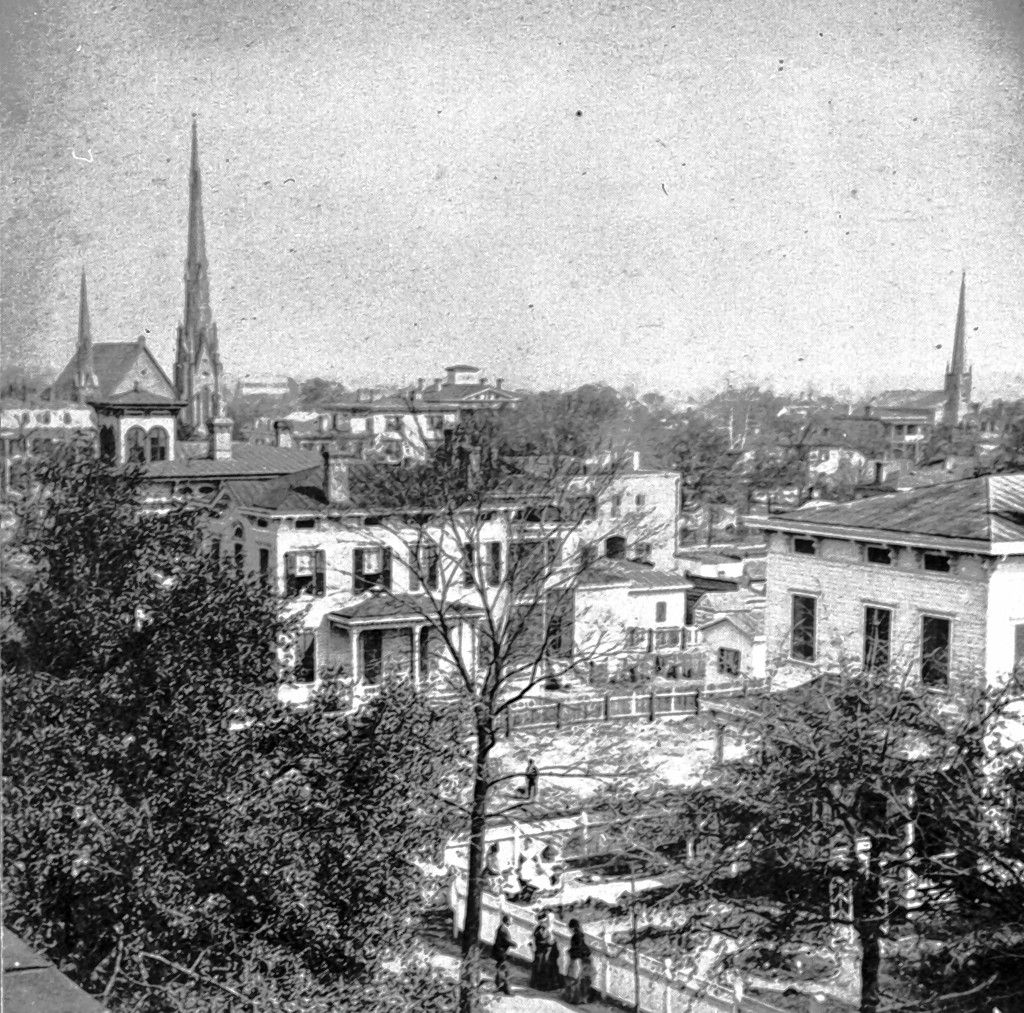

Wilmington, N.C., circa 1898. The city was almost 60 percent black at that time; today it is 18 percent black.

Yet more and more blacks were registered to vote, and a solid black working class and middle class began to emerge in Wilmington. By 1880, Zucchino writes, Wilmington, a shipbuilding center along the Cape Fear River in southeastern North Carolina, had the highest proportion of black residents — close to 60 percent — of any Southern city. African Americans also served alongside whites in a number of positions in local government, including on the police force. Blacks and whites in some cases were neighbors — a situation some whites could not abide.

A violent coup

By 1898, Democrats controlled much of the South, but North Carolina had a Republican governor, Daniel Russell, elected with strong black support, especially from Wilmington. Democrats became determined to oust him and to put an end to black voting itself.

“[T]here is one thing the Democrat Party has never done and never will do — and that is to set the negro up TO RULE OVER WHITE MEN,” wrote Furnifold Simmons, chairman of the state Democratic Party and a leader of the white supremacist campaign. “[N]egro rule is a curse to both races.”

As Zucchino outlines, white newspapers and Democratic leaders pounded on this theme for months. At a huge rally of whites in Wilmington, one speaker thundered that blacks and the “handful of white cowards” who led them would be defeated “if we have to choke the Cape Fear with carcasses!” Gun shops reported record sales to whites but refused to sell weapons to blacks.

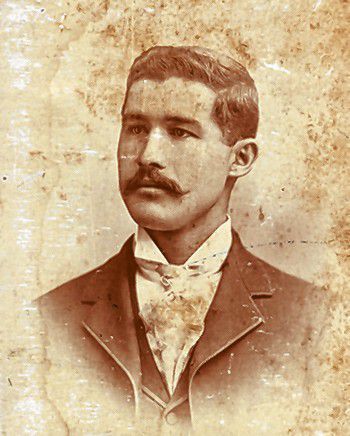

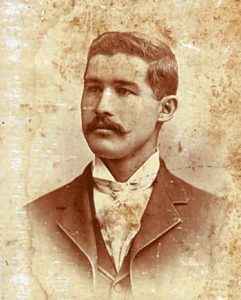

Alexander Lightfoot Manly, the grandson of a former white North Carolina governor and a black slave, edited a black newspaper in Wilmington.

In August, Democrats found another way to stoke white rage. Alexander Lightfoot Manly, the editor of a black newspaper in Wilmington, The Daily Record, responded to calls for lynching black men accused of raping white women with an editorial that said white men raped black women with impunity. The piece also suggested some white women loved or even lusted after black men, upending “the core white conviction that any sex act between a black man and a white woman could only be rape,” Zucchino writes.

“Don’t think ever that your women will remain pure while you are debauching ours,” Manly wrote. “You sow the seed — the harvest will come in due time.”

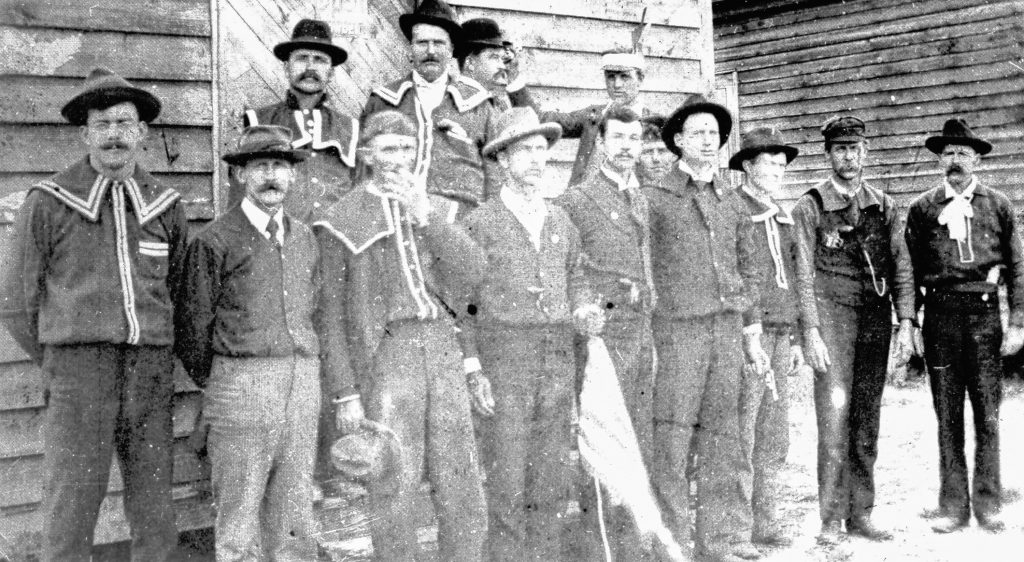

Though some whites immediately called for destroying The Daily Record office and lynching Manly, Simmons and other white supremacist leaders urged restraint, saying payback would come at the ballot box. So on election day, Nov. 8, some 2,000 heavily armed white men, collectively known as “Red Shirts,” were essentially deputized as militia and flooded Wilmington. Federal troops, some just back from fighting in the Spanish-American War, were also on hand to help keep “order.”

Not surprisingly, black voters barely showed up at the polls, and the Democrats swept almost all state and local offices in North Carolina. Actual violence had been fairly minimal, but Red Shirts and other whites in Wilmington, Zucchino writes, were still “eager for a confrontation.” They provoked one on Nov. 10 when, responding to rumors of gatherings of hostile blacks, they began shooting African Americans throughout the city, causing hundreds of others to flee to swampland outside of town. Vigilantes also torched The Daily Record office, but Manly, the editor, had already fled.

Zucchino’s account makes for harrowing but can’t-turn-away reading; he basically describes an armed overthrow of a lawfully elected government and open murder of innocent people. Yet this violent coup was celebrated by white supremacists not just in North Carolina but throughout the South (“Old North State Redeemed From Negro Rule At Last” read a headline in the Atlanta Constitution) and even in other parts of the country.

“Red Shirts,” white men who formed an ad hoc militia in North Carolina, outside a polling place in Wilmington, where they intimidated blacks into not voting.

U.S. President William McKinley, whom black leaders had implored to intervene in Wilmington, did nothing, according to Zucchino, and none of the white killers was ever prosecuted. The Republican governor, Daniel Russell, was too frightened to intercede. Afterwards, efforts to disenfranchise African Americans in the state through other means — poll taxes, literacy tests, voter-roll purges — reduced registered black voters from 126,000 in 1896 to 6,100 in 1906.

By contrast, a number of leaders of the Wilmington coup rode their fame straight to prominent positions in state and federal government, including Simmons, the Democratic Party chairman; he became a five-term U.S. senator. The African-American presence in Wilmington was permanently reduced, notes Zucchino. Today, just 18 percent of residents are black.

“Wilmington’s Lie” is one of the most disturbing and frightening books I’ve ever read. It should be required reading for whites who scoff at the idea of white privilege.

Steve Pfarrer can be reached at spfarrer@valleyadvocate.com.