On the evening of Oct. 29, 1915, a group of 500 women of the Equal Suffrage League, dressed in white, and wearing, across their chests, gold sashes emblazoned with VOTES FOR WOMEN, gathered in the alleys around their headquarters on Center Street in Northampton.

At 7:40 p.m., they stepped off to march four abreast, accompanied by the beat of the Corticelli Drum Corps. Japanese lanterns carried on staffs lighted the marchers’ way and a few men supporters and a cortege of cars brought up the rear.

They used a serpentine route to reach their goal of City Hall, maximizing their time on Main Street. From Main they marched to State, turned at Trumbull, and proceeded up King to arrive back on Main Street again. They then headed up Main, passing the Academy of Music to climb College Hill. Finally, they turned their mighty line, proceeding downhill to City Hall, and packing into its large, second-floor auditorium.

The guest speaker from Nevada gave a rousing account of the successful campaign the previous year that gave women the vote there, joining four million other enfranchised women in 15 states, all west of the Mississippi. The Daily Hampshire Gazette’s editor, an opponent of woman suffrage, noted that the march exceeded the combined size of the Democratic and Republican parades held in the run-up to the Nov. 3, 1915 election. Crucial to the marchers in that upcoming election would be a ballot initiative to amend the state constitution so that Massachusetts women could at last vote.

Since 1914, the suffragists had conducted an indefatigable grassroots campaign to convince men voters to vote yes via canvassing, newspaper ads, mailed leaflets and others they handed out at factory gates. They built momentum for their cause with informational tables at the Cummington fair, and a street rally in front of what is now the Silverscape building. They wrote endless letters and held small meetings with key politicians, then redoubling their efforts with Northampton men’s clubs, from the German Americans to the Knights of Columbus.

Their campaign actually began four years earlier when Ruth Huntington Sessions called the first Northampton meeting of the Equal Suffrage League on March 24, 1911, at her home on Elm Street, now the Sessions housing complex on Smith College campus. Ruth’s husband was a music professor at Smith and Ruth herself was trained in piano in Germany. A descendant of the Phelps family, she summered in Hadley at what is now the Porter Phelps museum.

Smith English Professor Elizabeth Deering Hansom, one of the first women to receive a Ph.D. at Yale, chaired the meeting. Also in attendance were Mary Peet Sleeper, a social worker active with MSPCC and later a national suffragist leader; and Dr. Grace Stevens of Bedford Terrace (a Mount Holyoke graduate who subsequently was among the first women to complete Boston University Medical School.) The gathering reflected the early 20th century shift in the suffragist movement. Previously participants were often the wives of men prominent in business, the clergy or academia.

Joining their ranks after 1910 were the increasing number of women professionals including clergy, doctors and professors, but also social workers, nurses, telephone operators and small business owners. This Northampton gathering included Katherine McClellan, who ran a photography studio at 44 State St., where she had once photographed Henry James. Although Northampton had women garment factory workers, this local group was unable to recruit them. Elsewhere in Boston, New York, Springfield and Holyoke, women labor union leaders espoused woman suffrage.

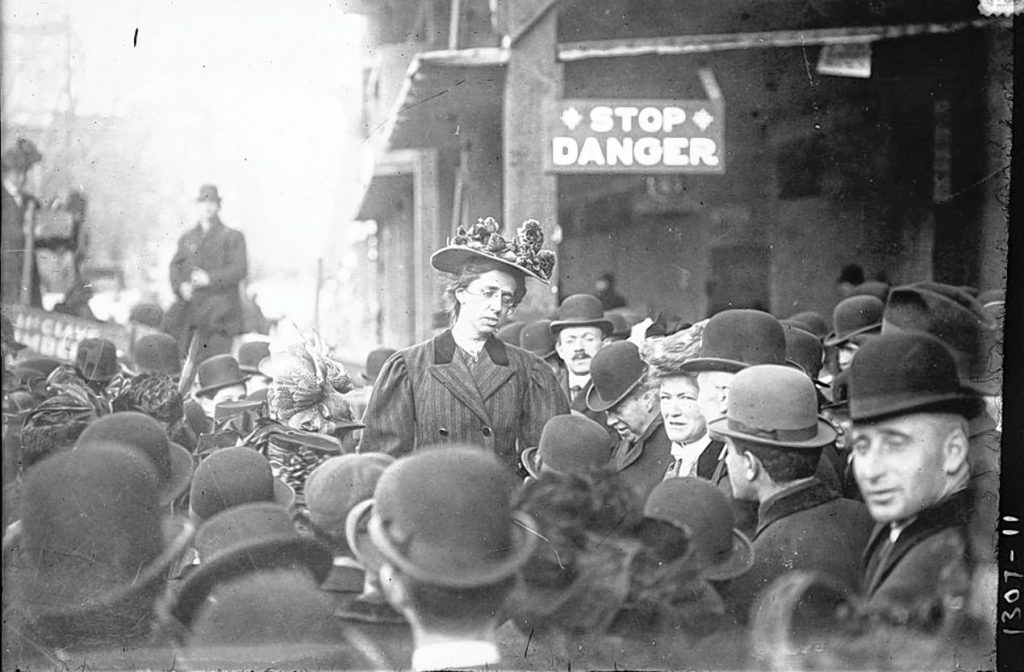

Three years later in 1914, eight members of the Northampton group joined more than 10,000 others to attend the first Massachusetts Suffrage parade in Boston on May 22, 1914. At 4 p.m., eight women marshals on horseback stepped off from the Common to lead a mile-long parade with 13 bands.

In the Northampton group were Lydia Ludden, business manager of the Hampshire Gazette, and Marion Mack Sheffield, a Smith graduate and the wife of Charles Sheffield, a silk manufacturer in Florence, who was also the author of a detailed history of 19th century Florence, including its abolitionist and utopian communities. Regarding that day, in a subsequent memoir, Ruth Sessions commented on having not outgrown the apprehension about “flaunting myself,” but also noted: “In my exalted frame of mind, I decided that the one way of achieving the devotion of an individual to a creed, was to make him march for it.”

Smith faculty and faculty wives had led the original group in 1911 and 140 of the 500 torchlight parade marchers in 1915 would be Smith students. They did not identify as from Smith within the larger group because the college’s President Nielson had forbidden students to march as a Smith contingent, there or in Boston, and opposed the formation of a pro-suffrage group on campus. Nielson did allow time for a pro and con suffrage discussion group, which then sponsored the legendary Anna Howard Shaw, trained as a minister and a physician, and the current president of the American Women Suffrage Association, to speak at John M Green Hall in 1915.

The opponents of suffrage, including many socially prominent women, argued that women did not want the vote, that it wouldn’t improve their economic or educational prospects and that they would lose their more protected status in the family if they received it. It was also argued that women needed to remain nonpartisan in their work on hospital and child welfare committees.

At the election on Nov. 2 ,1915, the referendum question regarding adding woman suffrage to the Massachusetts Constitution was defeated in Northampton 789 to 2,917, with similar, 2 to 1, margins of defeat statewide. A similar referendum in New York state also failed.

Despite this setback, the ranks of suffragists continued to swell. A dual strategy campaign began nationally to bring the issue to other states, but also to pursue again a national amendment with state ratification. Carrie Chapman Catt, first president of American Woman Suffrage Association, came up with a strategy for lobbying the vacillating President Wilson in order to find the support in the U.S. Senate to pass the constitutional amendment.

This was in counterpoint to the first ever daily picketing of the White House at Lafayette Square by Alice Paul and Lucy Burns of the National Women’s Party – a tactic disavowed by Catt as unpatriotic in wartime and thus counterproductive. The picketers gained support in 1918 however, after they were sentenced to a workhouse for “loitering” and tortured there with forced feeding.

Locally, by 1917, the Northampton group had grown to 569, with evening meetings to accommodate working women at the Plymouth Inn on Green Street and an independent group meeting in Florence at Hill Institute. Because Massachusetts women had been able to vote for school committee members since 1879, and could legally hold any political office, meetings were held with Democratic and Republican party leaders in Northampton’s seven wards asking for various women to be nominated, without success. Door-to-door canvassing was used to recruit women to register and to vote for school committee candidates.

The Final Phase

By 1919, inflation, unemployment and massive strikes followed the World War I Armistice of Nov. 11, 1918.

The “Spanish flu” pandemic, which began in military camps at home and in France, came to Massachusetts via the port of Boston and then Army Camp Devens. Nationally, the flu killed 500,000 Americans in a few months in 1918. Alexander Graham Bell related in an October letter that 100 children had fallen ill and two had died at the Clark School for the Deaf. Grace Goodhue was working there when she met Calvin Coolidge in 1904. Calvin Coolidge, since 1910, had successively been mayor of Northampton, Hampshire district legislative representative and then state senator, lieutenant governor and then governor, while continuing to live on Massasoit Street.

The population of Massachusetts at that time was 28% foreign-born and 25% of manufacturing employees were women. In the face of labor unrest and the Russian Revolution, anti-immigrant feeling was easy to promote. The notorious Palmer raids beginning in November 1919, sought to deport “radicals” and “anarchists” of the labor union movement.

The Gazette of Jan. 4, 1920 reported noncommittally that 63 “reds” were arrested in Springfield, Holyoke and Chicopee. Nationally 3,000 were arrested, due process was frequently denied, and 556 were deported. The Springfield Republican uncritically reported the conviction and sentencing to death of African American “radicals” in Arkansas for “insurrection” and “planned killing of whites,” an event known as the Elaine Massacre, that would later be revealed as white vigilante killing of hundreds of African American sharecroppers who had organized as a union.

Surprisingly, in these tumultuous times, the cause of suffrage advanced. The liquor industry had opposed it, but once prohibition was passed in the 18th amendment in the summer of 1919, suppressing women’s support of temperance became moot.

More important was the increased visibility and esteem accorded to women for their contribution to the war effort. Carrie Catt strategically founded the Women’s Committee of the National Defense League that sold war bonds and promoted Victory gardens, but also collaborated with the Red Cross to train women volunteers to serve as nursing assistants in the pandemic, and as nurses for military camps at home and in France.

The U.S. Congress had passed the 19th Amendment to give women the vote on June 4,1919. Ratification by 36 states was needed to make it part of the U.S. Constitution. The Springfield Republican reported the vote of the Massachusetts House of Representatives to ratify the 19th amendment on June 25, 1919. The gallery for the final debate was reserved for women with separate sections for pro- and anti-suffragists. The opposition legislators, wearing red rose boutonnieres (the pro-suffragists had yellow roses) sought one amendment to require, preliminarily, a repeat of the 1915 referendum, and another to limit suffrage to white women.

These both failed, and the final roll call vote was 185 to 47. Only 10 of 31 representatives from western Massachusetts opposed the amendment, with none from Holyoke or Northampton. Adjacent to the local newspaper account was a report of the return home of Miss Helen Miles, a nurse trained in Westfield at Noble Hospital, who had “mustered out” after serving with the Red Cross as a nurse at a U.S. military hospital in France. This hospital, like others, had been built with funds raised by Carrie Catt’s Women’s Committee of the National Defense League.

Tennessee became the crucial 36th state to ratify the 19th Amendment on Aug. 18, 1920. The Springfield Republican on Nov. 3, 1920, reported the Presidential election: “SWEEP FOR HARDING AND COOLIDGE. BIGGEST REPUBLICAN VICTORY EVER!” and a triumph for women as well. Turnout for registered women voters was greater than 90% and exceeded that of the men. “Women took their place in the electorate in a business-like fashion with no fuss,” the paper reported. A Pittsfield journalist observed, “The women took less time to mark their ballots than the men.”

The success of the women’s suffrage campaign, which had begun 72 years before in 1848, was thought unlikely in 1916. It was unprecedented when it occurred in 1920 in the face of the post-war depression, rising anti-immigrant sentiment and labor unrest, and the third wave of the pandemic. The leaders were brilliant, strategic, monomaniacal, combative, tireless, and flawed. Carrie Chapman Catt publicly denounced Alice Paul’s picketing to the New York Times. Her transactional support of World War I through the Women’s Committee resulted in her ejection from the Women’s Peace Party which she had co-founded.

African American suffragist leader Mary Church Terrell, with her daughter, had answered Alice Paul’s call to picket the White House. But Alice Paul refused to campaign subsequently with African American suffragist club members. Carrie Catt sought support from white supremacists and nativists by suggesting that giving the vote to educated white women would “balance” the vote of the “uneducated Negro and the dago.”

Carrie Chapman Catt, with Anna Howard Shaw, aspirationally founded the League of Women Voters, on Febru 14, 1920, six months before the complete ratification, to “finish the fight” to provide access to the vote for all, and to advocate for the issues of importance to women and the community. Alice Paul co-authored the Equal Rights Amendment in 1923! It still awaits final ratification.