Sometimes in the course of the past year I despaired of ever again hearing that mantra of curtain speeches in the cyber-era: “Please silence your cell phones” – or of hearing the words spoken by Julianne Boyd on Barrington Stage Company’s opening night: “I want to welcome you to live theater!”

Last week it happened, as two Western Mass companies greeted live audiences with live performances. Barrington’s offering was Who Could Ask for Anything More? The Songs of George Gershwin, a big, brassy cabaret-cum-celebration. Chester Theatre Company countered with Title and Deed, a quiet solo show traversing some of the themes that have permeated our lives during this pandemic season.

Covid, of course, is not “over,” though it’s all too tempting to throw off all restraints, and we were reminded of that by Actors Equity rules that still require audiences to be masked. Even so, it was great to be back in the theater, albeit makeshift ones, and the excitement in the air was palpable as we took our seats on safe-distanced folding chairs under big open-sided tents on the outskirts of Pittsfield. (Chester’s season has been moved from its usual hilltop home to a verdant corner of Hancock Shaker Village.)

BSC’s production is an original confection created by Boyd and musical director Darren R. Cohen. It’s a potpourri of some two dozen songs from Gershwin musicals of the 20s and early 30s – staples of the American Songbook balanced by specialty numbers from long-forgotten shows – as well as a trio of pieces from Gershwin’s opera, Porgy and Bess.

For me, the pleasure of basking in Gershwin songs is not just George’s elegant melodies and fascinating rhythms, but brother Ira’s mischievous lyrics. Take, for instance, this audacious triplet in “But Not for Me” – “With love to lead the way/ I’ve found more clouds of grey/ Than any Russian play/ Could guarantee.” Or the cowpoke’s song in Girl Crazy: “I’m bidin’ my time/ ’Cause that’s the kind of guy I’m.”

A five-piece combo seated in an Art Deco bandstand is fronted by a lively quintet of singers, both newcomers and familiar faces. The ensemble’s keystone is Alan H. Greene, known here from a half-dozen Barrington musicals and dramas. Here his moods range from pensive to playful, hopeful to heartsore, and his easygoing charisma welcomes us and centers the ensemble.

Britney Coleman brings willowy poise and a mile-wide grin to such standards as “’S Wonderful.” Alison Blackwell lends a wistful longing to “Someone to Watch over Me” and a coy twinkle to “I’ve Got a Crush on You.” Alysha Umphress, another Barrington veteran, is not only a legit singer but a jazz diva with a nice line in scat, which she showcases in the custom vehicle “Little Jazz Bird” and the shamelessly horny “Do It Again.”

All three ladies cluster around bassman Mitch Zimmer for some Andrews Sisters harmonizing on “Slap That Bass.” Jacob Tischler takes the comic juvenile roles in show, stepping into the occasional soft shoe (Jeffrey L. Page did the choreography) and pairing up with Coleman for a couple of flirtatious duets.

Two songs from that opera invite us to reflect on the other pandemic of the past year (and more). In “Summertime,” Alison Blackwell’s performance subtly steers the lullaby into an elegy and finally an indictment in which we can hear the anguish of mothers whose children are victims of living while Black. And Alan H. Green turns “My Man’s Gone Now” — in the opera a woman’s lament for her dead husband — into his own sorrow over a murdered friend.

All five performers are gifted pros with great voices and appealing presence, and I felt that, on opening night anyway, they were trying harder than necessary, overselling some of the songs and diminishing their variety.

The show ends with another Porgy and Bess number, “There’s a Boat That’s Leavin’ Soon for New York,” this time carrying, as Green explains, the performers’ aspirations as Broadway reopens. We wish them well there, but for now, we can be glad they’re here.

Stranger in a Strange Land

In addition to delivering the traditional cell phone caution on Chester Theatre’s opening night, the company’s director, Daniel Elihu Kramer, observed in a program note what we’ve all been missing – the fleeting but powerful bond formed by a theatrical performance: “We gather artists and audience in a shared space, and something passes back and forth.… Before the play began, we were among strangers, but now we share this experience, this brief community.”

That truth is particularly relevant to the first show in Chester’s three-play season. It’s Title and Deed, by Will Eno, who’s been called “a Samuel Beckett for the Jon Stewart generation.” The lonesome traveler in this one-man colloquy with the audience carries with him a lot of the feelings we’ve experienced over the past lonely year.

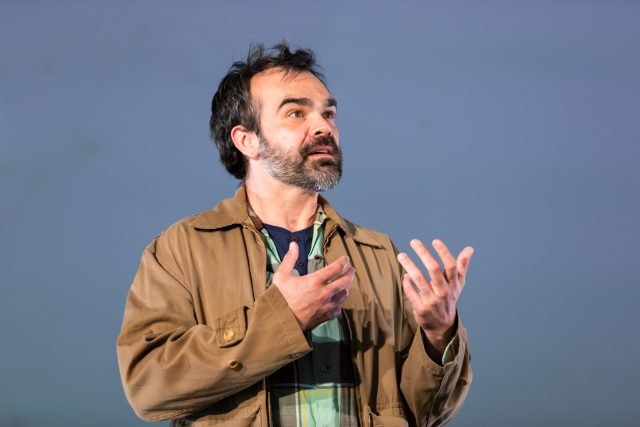

At the beginning of Keira Naughton’s production, this unnamed fellow, winningly played by Berkshire favorite James Barry, enters the theater (yes, let’s call it a theater, for now), mounts the stage and disappears into a tall boxy structure with a single door, through which he soon re-enters – an apparent metaphor for our return to the theater and the stage.

“I’m not from here,” he begins, addressing us. “I guess I never will be. That’s how being from somewhere works. I’ll assume you are, though.” And for the next 75 minutes he gives a scanty, digressive account of who he is and where he’s come from – teasing hints that eventually resolve in our realization that as different as we may appear to be, not only from him but from each other, we’re all in the same life/boat, adrift in a sea of uncertainty, clinging to “a hopeless little glimmer of hope.”

“I’m not from here,” he begins, addressing us. “I guess I never will be. That’s how being from somewhere works. I’ll assume you are, though.” And for the next 75 minutes he gives a scanty, digressive account of who he is and where he’s come from – teasing hints that eventually resolve in our realization that as different as we may appear to be, not only from him but from each other, we’re all in the same life/boat, adrift in a sea of uncertainty, clinging to “a hopeless little glimmer of hope.”

Here’s where Beckett’s shadow falls. This and other moments kept reminding me of a line in Waiting for Godot: “Astride of a grave and a difficult birth.” But Eno’s Everyman is not exactly pessimistic. That hopeless hope is an affirmation in its way that life’s very brevity is an invitation to make the most of it. And that invitation, spoken by a “homesick orphaned fuck,” is more than anything a call to fellowship and community.

“People don’t gather enough anymore,” he says, and Barry pauses a beat to let us register the now-topical irony, which resonates more somberly when the man contemplates the place he’s just come from: “All those losses.”

The theme may be Beckett-bleak but its delivery is wry and whimsical, sometimes feeling like a deadpan stand-up act sprinkled with non sequiturs and ironic one-liners: “I like repeating myself, because, you know, who else is going to do it?” His parents, he says, “loved me like only they could, with penetrating questions like, ‘And where do you think you’re going?’”

He’s constantly groping for the right word, turning over meanings, despairing of the inadequacy of language, “these frail little sounds, made up out of nowhere,” while also delighting in wordplay and puns: “Love is a many-splintered thing.”

The man’s, and even more the actor’s relationship with the audience is direct and personal. He addresses us as a whole and as individuals, turning to front-row patrons for questions and asides. And there’s a constant recognition of the here-and-now. At the outset he notices the tent pole that bisects the apron of the stage. “There’s a giant pole here,” he remarks, then shrugs it off. Twice during the performance the lowing of a cow in the neighboring field made Barry stop and glance over with a little smile, then carry on.

The man’s, and even more the actor’s relationship with the audience is direct and personal. He addresses us as a whole and as individuals, turning to front-row patrons for questions and asides. And there’s a constant recognition of the here-and-now. At the outset he notices the tent pole that bisects the apron of the stage. “There’s a giant pole here,” he remarks, then shrugs it off. Twice during the performance the lowing of a cow in the neighboring field made Barry stop and glance over with a little smile, then carry on.

I wished he’d been given more latitude for improvisation in moments like that, instead of sticking to mute reactions. I also wished that, probably contrary to the playwright’s intentions, he had taken more of an emotional journey, letting the character’s bewildering predicament carry him further afield from his sardonic musings.

Quibbles aside, it was bracing to experience a play with so many resonances to where we’ve just been and are now, and wonderful to see a consummate actor plying his craft before us – that is, with us.

And as if to remind us that we really were back in the theater, in the middle of the show a cell phone began chiming in the front row. Barry paused meaningfully as the embarrassed patron groped for it in her handbag, finally turning it off. And the show went on.

Songs of George Gershwin photos by Daniel Rader

Title and Deed photos by Elizabeth Solaka

In the Valley Advocate’s present bi-monthly publication schedule, Stagestruck will continue to be a regular feature, with additional posts online. Write me at Stagestruck@crocker.com if you’d like to receive notices when new pieces appear.

The weekly Pioneer Valley Theatre News has comprehensive listings of what’s on and coming up in the Valley and beyond. You can check it out and subscribe (free) here: http://www.pioneervalleytheatre.com/

The Stagestruck archive is at valleyadvocate.com/author/chris-rohmann

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email Stagestruck@crocker.com