When Charles Neville died in 2018, many mourned the passing of a superbly talented musician who not only played in a variety of styles but who by all accounts was unfailingly generous about sharing his music with fellow players and fans alike.

And Neville, a saxophonist who earned the sobriquet “The Horn Man” for his distinctive sound, was also someone who’d come through serious trials in his life and arrived at a place of acceptance and self-acceptance.

As Northampton musician Roger Salloom recalled in an interview with the Daily Hampshire Gazette after Neville died at age 79, “He was kind, he was gentle, he was forgiving, and he was at peace with himself.”

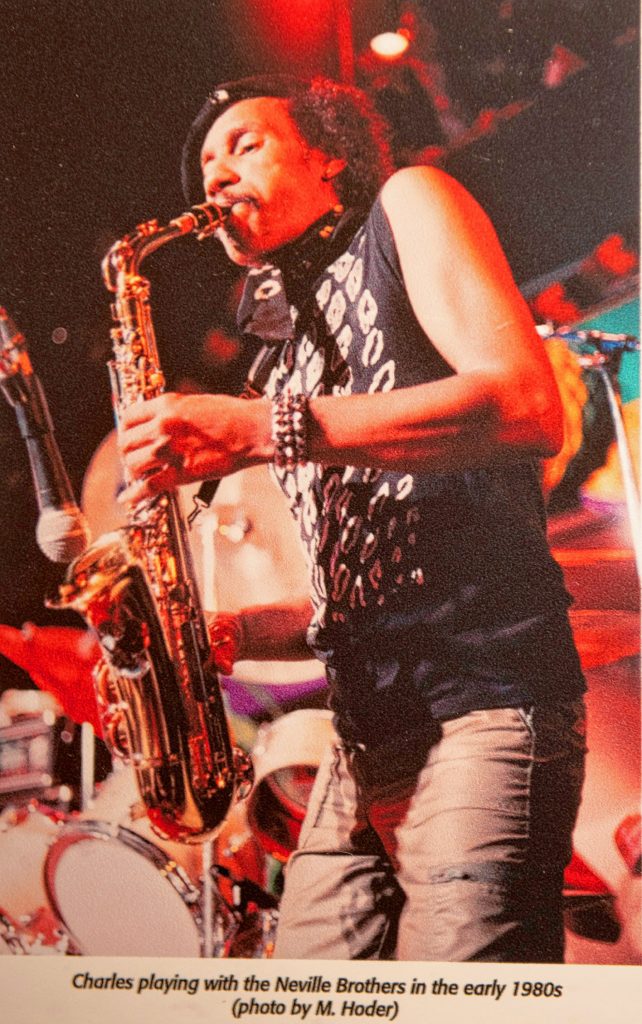

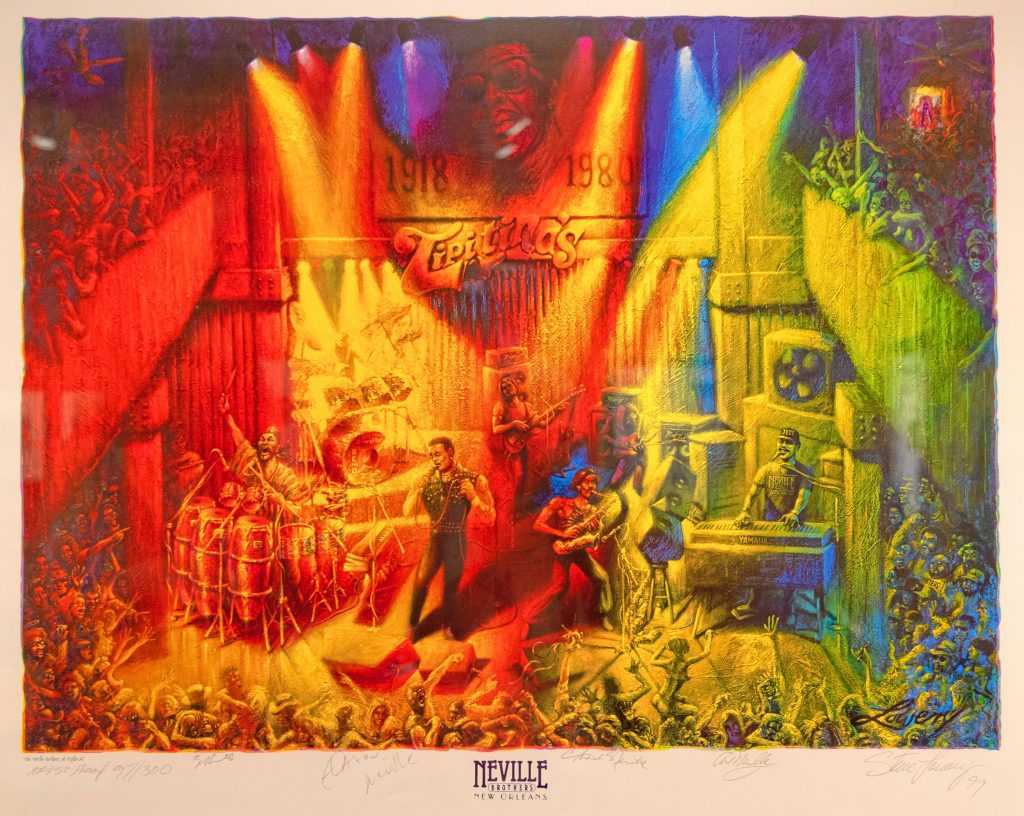

A new exhibit at the Springfield Museums pays tribute to Neville’s long life and career, from his birth in New Orleans and his days as a touring musician in the Jim Crow South, to a stint in a tough Mississippi prison and struggles with drugs — as well as his rebirth in the 1970s when he reconnected with his siblings to form The Neville Brothers, the popular R&B, soul, jazz, and funk group that toured nationwide and overseas and won a Grammy in 1989.

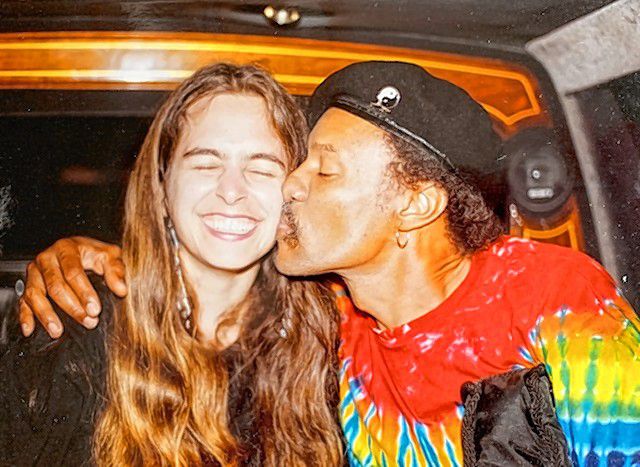

The exhibit, “Horn Man: The Life and Musical Legacy of Charles Neville,” also encompasses another significant chapter of his life: meeting his future wife, western Massachusetts native Kristin Gaitenby Neville, in 1990, which would lead to their marriage, two children, and a move to Huntington in the late 1990s.

Neville then became a key figure in the Valley’s music scene, even as he continued to tour elsewhere and play with a range of musicians.

The exhibit, at the Wood Museum of Springfield History, will run through Nov. 28.

Last fall, Kristin Neville got in touch with museum officials to propose the exhibit. One key connection, she said in a recent interview at the show, was the volunteer teaching her husband had done with the Community Music School of Springfield, as well as his participation in the Springfield Jazz & Roots Festival, an annual event Kristin Neville co-founded in 2014.

“Music was such a big part of his life,” said Neville. “That was his passion, and sharing it with people, using it to bring people together, was so important to him.”

Maggie Humberston, curator of Library and Archives for Springfield Museums, said given the Wood Museum’s focus on Springfield history, it was important that Charles Neville’s story have resonance in the city.

And it did, Humberston added: “We jumped on this. Kristin made a very good case for the exhibit, and we’re thrilled to be doing it.”

She notes that at a time of larger racial reckoning across the country, “Horn Man” also speaks to broader issues in American society and history.

The show includes a host of memorabilia and other items from Neville’s career: photographs and notebooks, concert flyers, one of his saxophones, some intricately carved wooden staffs he made, as well as a number of his paintings. He first took up painting when he was jailed for possession of marijuana in the early 1960s at the notorious Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, a prison (and former slave plantation) sometimes called the “Alcatraz of the South.”

Kristin Neville has created several large text blocks, all of which include period photos, that describe different periods of her husband’s life, from his boyhood in New Orleans — he was born in 1938 — to his time as a traveling musician in the segregated South and then his move first to New York City and then to Massachusetts.

There’s a picture of a smiling, cherubic Charles, about age 9, from elementary school, and another of him from a two-year stint he did in the Navy in the 1950s. There’s a period shot as well of a legendary New Orleans club, the Dew Drop Inn, that he played in during the 1950s.

Finding his way

But a larger story told on these boards is the ingrained racism and oppression Neville and other Blacks had to battle in the South, a stifling force that Kristin Neville said contributed to his move into drugs and his sense, when he was younger, that the skills he had to offer the world “just weren’t valued or recognized.”

“He grew up in an environment of fear,” she added. “It was something that was ever-present in Black-white relations … and it got in the way of how he wanted to express himself creatively.”

Neville eventually conquered his addiction through methadone treatment and his exploration of Eastern religions. Kristin Neville says her husband also took up tai chi in the 1980s, and the discipline he developed through that helped him kick drugs and bring a new serenity to his life — an inner peace that then flowed out through his music.

And the exhibit describes how Kristin and Charles met in 1990 in New Orleans, when he was playing a show with The Neville Brothers and she was working at a food bank in the city as a VISTA volunteer.

She jokes that she was able to get into the front row of the concert and at some point made eye contact with Charles. That was a thrill alone, she said, something she imagined sharing with her mother: “Charles Neville smiled at me!”

In fact, they were introduced after the show, and love blossomed down the road; the couple married in 1995 and had two sons, Khalif and Talyn, who both grew up to play play music with their father (Khalif Neville is a now a multi-instrumentalist and singer/composer).

Humberston says one of her great takeaways from the exhibit is the resilience and determination Charles Neville demonstrated, the way he rose above the Jim Crow South and his personal struggles to find peace in his life, satisfaction in his music, and an acceptance of people on their own terms.

“He just showed remarkable spirit, and I think he used music to keep himself centered,” said Humberston.

The exhibit includes five sound stations — you activate them by stepping on them — that offer playlists of songs Neville either played on or which represent the style of music he was performing at different times in his career (Khalif Neville helped create the sound stations, his mother says). There are other important keepsakes from the “Horn Man” on display, such as the yin-yang necklace he often wore, and a tie-die shirt he favored.

Humberston and Kristin Neville say they hope to build links between the exhibit and this year’s Springfield Jazz & Roots Festival, taking place in August, as well as connections with Springfield Schools. Neville has partnered with other organizations in the city to create the Charles Neville Legacy Project, through which, beginning this fall, Black musicians will serve residencies in Springfield high schools to lead classes examining the Black and Caribbean roots in American music.

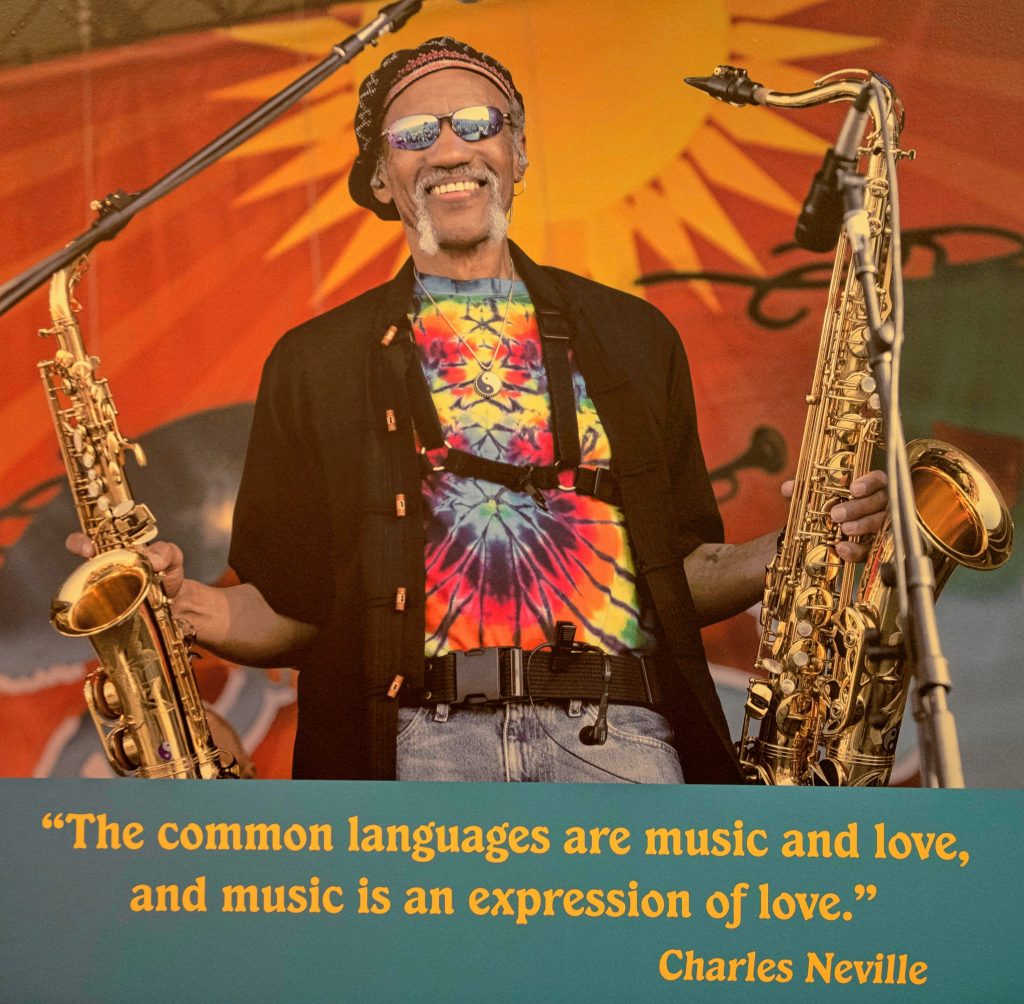

Music, after all, was what Charle Neville was all about. As he once said, “The common languages are music and love, and music is an expression of love.”

For more information on “Horn Man,” visit springfieldmuseums.org and follow the link for exhibitions.

Steve Pfarrer can be reached at spfarrer@gazettenet.com.