When it’s right in front of you, like the nine decaying cherry trees on Northampton’s Warfield Place that the city of Northampton recently removed in order to rebuild the road and sidewalk, residents lose their minds.

Some likened the tree-cutting “violence” to napalm deforestation during the Vietnam War and “ordained” the trees as Zen Buddhist monks, while others climbed the trees and brought on arrest, clinging to their limbs in protest.

Though the justification for the trees’ destruction may still be up for social media debate, no one would argue that the city’s actions were motivated by greed.

But not too far away, in the fertile farmland of Northfield and in the deep forests of Shutesbury, where massive solar projects are proposed, some say it may not be so hard to make that case. Now, residents are speaking out against these developments.

Statewide rallies took place this summer demanding a moratorium on funding for large-scale solar projects. The moratorium calls on Gov. Charlie Baker and Secretary of Energy and Environmental Affairs Kathleen Theoharides to hit the brakes on the many planned projects that they say clear-cut forests and remove prime farmland from production. One rally was held at Recreation Energy Park in Greenfield on a gorgeous July Saturday bathed in ironic sunshine. The groups, which include Save the Pine Barrens, Save Massachusetts Forests and the Herring Pond Wampanoag Tribe, charge that the state’s solar incentives are driving reckless, unregulated development by big corporations.

The groups, along with Sunrise Amherst, support passage of bills H.1002 and H.912, designed to protect land, trees and habitats while transitioning to green energy.

“Our forests are of increasingly critical importance as we face the dual crises of climate disruption and mass extinction,” said Bill Stubblefield of the Wendell State Forest Alliance, a group that clashed with the state in 2019 after the logging of 100-year-old oak trees in an 80-acre stand. “Destroying forests to produce energy, even solar energy, just doesn’t make sense when we consider their irreplaceable ability to sequester carbon and preserve biodiversity.”

A bill introduced by state Rep. Lindsay Sabadosa, HD.3685, seeks to hold the state accountable for environmental impacts and carbon accounting when it comes to forest management, also referred to as “sustainability measurement,” a process that strives to provide a factual yardstick for carbon-based decision-making. Stubblefield says that’s “the only way we get to a livable planet,” warning of what scientists call an “insect apocalypse,” caused by dwindling habitat and severe weather patterns.

“You will lose the diversity both above and below ground” if forests are cut down to make way for solar projects, he said. “It is painfully short-sighted that we subsidize such activity. Let us first use all the land already dominated by humans — parking lots, roofs, landfills and brownfields. Come talk to me when those sites are fully deployed, not before.”

In most surveys, 90% of Americans support expanding solar power and renewable energy in general. But does “renew” enter into it if you’re destroying hundreds of acres?

“Their (companies pitching big solar projects) business model is an attempt at an end-run around the town’s voter-approved solar bylaws,” said Shutesbury’s Leslie Cerier, who told of the stormwater runoff that floods neighbors’ homes due to earlier clear-cutting for solar. “We are all for small-scale solar. But what we are looking at here is the destruction of forests — part of the solution to the climate crisis — one solar panel at a time. What’s happening in my town, even with bylaws that say they can’t do this, can happen in any town in Massachusetts.”

Cinda Jones, CEO of the W.D.Cowls Co. of Amherst, who’s hosting the solar farms in Shutesbury, Pelham and Amherst, questioned the outrage in a recent column in the Gazette. “Shutesbury is 87% forested and 80% of its open space is under mostly permanent protection. The land under solar panels remains mostly permeable meadow wildlife habitat. Harvesting energy from the sun displaces more carbon than trees can store.”

“That’s too simple a calculation,” Stubblefield said. “Older forests store more carbon at higher rates. It’s not enough to eliminate fossil fuels, you need a way to eliminate carbon. These systems already exist. We call them forests. All we have to do is get out of the way and let them do their job.”

Bill Moomaw, a climate scientist at Tufts University, believes that halting the rise in heat-trapping gases into the atmosphere will require growing existing forests more and restoring what’s been lost. “Solar panels belong on rooftops and wasteland,” he said in a statement. “They do not belong on permanently deforested lands!”

But Jones cautions against throwing out the baby with the bath water. “The parcels in question are developable and will host either solar or residential subdivisions in the future. Shutesbury just got broadband and therefore has increased housing interest and demand. These towns need new revenue streams and could make maybe a million dollars a year in solar payments by allowing a few 30-acre patch cuts in the woods.”

Yes, it would seem that patch cuts and subdivisions are both looming in these places, but Jones makes a point about cash-strapped towns, which will often bear the burden of the state’s policy, or reap the benefits, depending on your point of view.

“Residents might be upset about losing that natural habitat,” said former Shutesbury Select Board member April Stein, “but sometimes you have to think of the greater good.”

The ‘greater good’ up close

The fenced-in and tucked away 30-acre solar farm on Amherst’s Pulpit Hill, the second project W.D.Cowls completed with solar company Lodestar, is an exercise in precision, thousands of panels lining up like a planted stand.

“A thing of beauty,” smiled Jones during a recent tour of the farm. Jones, along with Cowls’ vice presidents Tony Maroulis and Shane Bajnoci, drank in a view of Mt. Toby that likely wouldn’t have been visible through the trees that once stood there.

Cowls, in business since 1741, owns about 10,000 acres in 30 towns. Jones says “Leasing more subdivisions would not benefit the town. Solar is the smartest thing a rural community can do.”

Jones dismisses the rooftop/parking lot angle as “a non-starter.” In order to work, solar farms need to be in close proximity to a power substation, in order to supply the grid with clean energy. The farther away, the higher the cost goes, to the tune of “a million dollars a mile,” Jones said.

Amp Energy out of Ontario, the company working with Cowls on the Shutesbury proposals, is ready to sink $10-12 million into upgrading the National Grid substation on Pratt Corner Road, but must soon have a commitment from the town, whose bylaws, Amp insists, are too restrictive, forcing the company to seek waivers under threat of litigation.

Cowls, meanwhile, has won several national wildlife and conservation awards and migratory birds have been known to nest inside the arrays, protected by its fencing. “That doesn’t feel wrong,” said Jones.

“There’s a generational aspect to it,” added Maroulis. “For 280 years Cowls has been thinking through generations, looking generations ahead. You can only anticipate what is needed, or what is wanted by a town.”

The company’s goal is, said Maroulis, is to devote 3-5% of what it owns to solar and 50% to conservation. “You’re worried about land running out; we’re worried about that too. Our conservation matches up with anyone but (with a climate crisis) we’ve got to get to some solutions soon.”

Though sympathetic to the fears of Shutesbury residents, “We have no choice but to put it on forest and farmland,” said Jones. “Shutesbury is very vulnerable to litigation. What we’re proposing challenges their world view but we’re all trying to achieve the same result — to combat climate change with the resources we have available.”

State’s solar push

It flies off the tongue, solar power, as friendly as the dimpled grin of the sun itself, beaming its rays directly onto the spoonful of raisins on your cereal box. The preferred image is that of the conscientious couple down the street, who, as long as they’re frugal, can light up their house, heat their water and power-up their electric cars with only the photovoltaic panels on their roof.

In fact, the Baker administration’s SMART program (Solar Massachusetts Renewable Target) offers substantial incentives to homeowners who do just that, the linchpin of the governor’s ambitious goal to transition the state’s energy consumption from carbon-based fossil fuels to 100% renewable by 2050.

But the most staggering part of the plan is the scope and pace of it. According to Community Land and Water Coalition, 4,000 acres of forest and farmland have been consumed by solar. And, cautions Mass Audubon, should the trend continue with large-scale ground-mounted arrays on forest and farmland, “more than 100,000 acres will be converted.”

Where all those acres come from is ripe for interpretation. Leave it to the big boys to figure a bulldozing way in.

“They’re monopolists,” says Stubblefield. “They want big units they can control. The public wants distributed power, not consolidated. We need a real rethink on this and don’t need policy that throws money at big corporations.”

Supporters of the moratorium claim that at least 1,700 acres of forest and farmland are at risk statewide. In Shutesbury, it’s 190 acres of forest to make way for five separate solar arrays, from the 60-acre parcel in Pratt South to the 20-acre parcel in Pratt West. In Northfield, it’s 76 acres of prime farmland, cut out of Four Star Farms, a 14-generation enterprise owned by the E’Toile family, who, in the last decade has converted the lion’s share of its 230 acres into growing hops for beer-brewing.

These are ground-mounted systems like the kind we see on the turnpike on our way to Thanksgiving dinner, not the type urged by Mass Audubon — ones installed on the rooftops of buildings or over parking lots, along rail trails, on top of brownfields or above those other money-raking abominations, landfills.

Large solar companies often make deals with municipalities offering annual “payments in lieu of taxes” arrangements that can be very hard for small revenue-strapped towns to pass up.

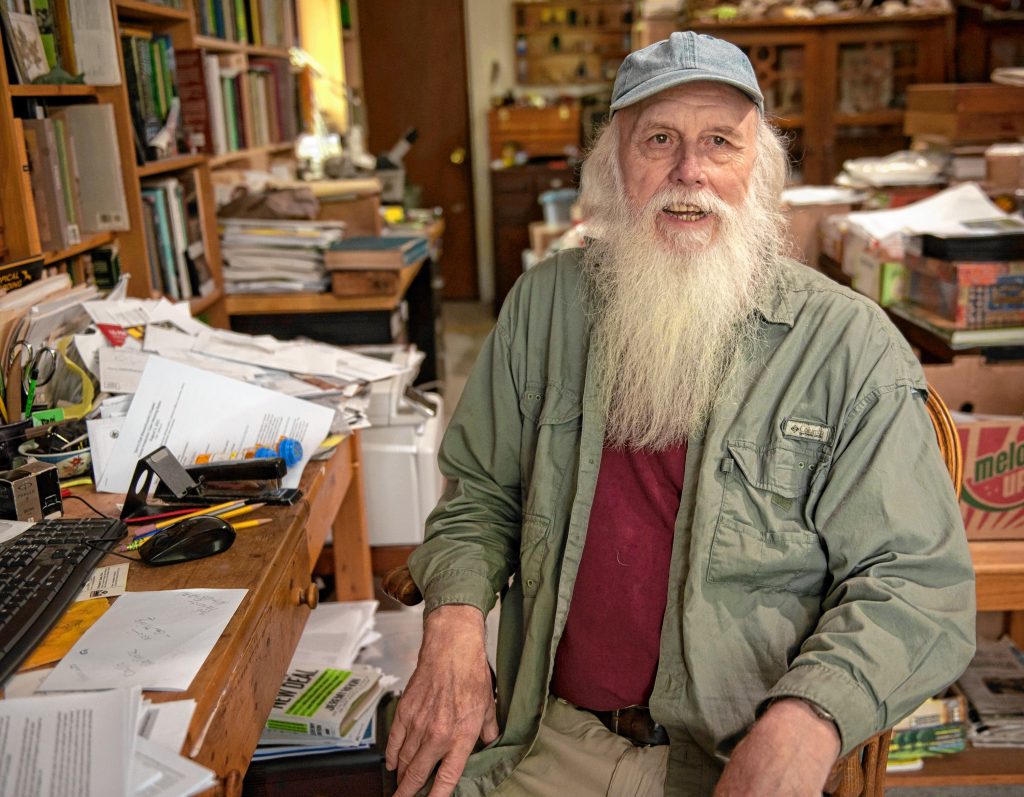

“Meet the new boss, same as the old boss!” cried Northfield farmer and historian Joe Graveline, insinuating through The Who that the big solar developers are nothing more than the fossil fuel dinosaurs with new titles on their business cards. “For over the last 1,800 years both indigenous and colonial societies have used the fertile bottom lands of the Connecticut River Valley for the highest and best use, to grow crops and nourish people. To take prime agricultural land out of crop production to make electricity is something we need to look at very carefully and up to this point we have not done that.”

As part of the state’s renewable energy acceleration, a municipality may not refuse solar, but officials can enact bylaws limiting the amount of it within their borders.

“As a longtime green-thinking person, I never thought I’d see forests and farmland destroyed in the name of green energy,” said Graveline. “People don’t have a sense how big this is — volunteer planning boards versus huge conglomerates. Talk about a mismatch. And they’ll sue towns who don’t buy in. We are extremely vulnerable without information.”

The solar moratorium seeks to temporarily stop the state from using taxpayer and ratepayer money to finance large solar projects — ones larger than 5 acres — allowing the public and experts time to work with lawmakers and regulators to fix what supporters say are problems with the state’s energy policy. “It’s a once-in-a-generation opportunity to take control of our energy needs,” said Graveline.

Large landowners, of course, are besieged constantly with attractive offers by moneyed sharps who gaze into the deep and timeless serenity of a canopied forest and see only condos, swimming pools, industrial parks and, in recent times, rows and rows of ground-mounted solar panels, even though studies undertaken by Mass Audubon show that 80% of the country’s electricity needs can be met by solar installed on existing infrastructure — albeit at higher costs.

And, though the industry has great interest in the unspoiled geographies of western Massachusetts, it has been busy on other corners as well.

“Southeastern Massachusetts is ground zero for solar gone wrong,” said Meg Sheehan of Save the Pine Barrens. “Since 2016 we have watched our beloved Pine Barrens forests — home to some of the world’s rarest plants and animals — be ripped out and destroyed for so-called ‘green energy.’”

Meanwhile, in Northfield, rancor is rife after a permit was approved allowing the sale of 76 acres of fertile, not marginal, bottom land to BlueWave Energy of Boston. Fred Beddall of Pie-In-the-Sky farm in Northampton, laments the lost farmland, “leaving farmers competing with solar developers for places to grow food. Our landscape is too small to devote it to something as monocultural as solar panels,” said Beddall. “If this was Iowa, you wouldn’t even notice. But this is half of what we have.”

Developers maintain that the arrays, since they’re mounted above the ground, leave the grass underneath in a permeable state, promoting a “dual-use” situation. Dual-use is in the lead paragraph of every permitting application put forth by solar corporations and by the language the state employs to encourage them.

In its introduction to Northfield residents, BlueWave Energy “believes wholeheartedly that the future of solar development is dual-use plus agriculture. By allowing the land directly underneath and surrounding the solar array to stay … dual-use allows farmers to manage the land according to their values.”

Beddall says no way.

“Dual-use is a big fat lie and everyone in favor of it is on the payroll of these solar companies. Look around at the farms in our region — what do you see? Potatoes, corn, apples, vegetables. You can’t grow any of those crops under solar panels. Trucking food from coast to coast is one of the biggest drivers of climate change. Local farms are already part of the solution. But you can’t do it under solar.”

Grazing sheep is often touted as one of the possible uses in “dual.” “It’s not because real farms can’t make it here,” said Beddall, “It’s that the commonwealth will pay you a whole lot of money to quit real farming and graze sheep.”

Graveline predicts a domino effect, with more and more farmers cashing in and getting out. “The cart is before the horse. The state doesn’t even know what dual-use is. They call it a 50% balance between agriculture and photo-voltaic. This has nothing to do with agriculture.”

“I voted for Charlie,” he adds, “but he wants this land just so he can take credit for transitioning off fossil fuel.”

Of the many promises made to municipalities, what Graveline calls “window dressing to get permits,” one would include the corporation planting pollinator-friendly plants around the installations. But who would we expect to keep up with all this friendliness?

“No one,” said Beddall. “A pollinator habitat takes constant attention and input. You can’t just plant something and walk away; it’s an ongoing effort. They’re just throwing buzzwords for the liberal public to feel good about.”

“They’re going after big landowners,” said Graveline, noting that he does not begrudge a fellow farmer making financial decisions to keep the operation afloat. “When you dangle these things in front of them, how can you blame them?”

Solar companies, like Amp Energy, insist that many building owners can’t host roof solar due to underlying structural or shading issues. Valid concerns — as any homeowner knows, the shelf life of a roof may not match up with the long-term demands of solar panels — but there are parking lots all around us as far as the eye can see. The ongoing solar project at UMass is canopied over a parking lot so vast you’ll forget which county you’re in as you search for your car.

“And we still have lots of landfills and lots of possibilities to make solar work,” says Graveline.

That said, a “grass” farmer from Southborough envisions success grazing his sheep and goats on those 76 acres in Northfield. BlueWave specializes in elevated solar panels 10 feet off the ground, involving no concrete footings or anchors, just single monopoles driven in deep, providing shade for animals grazing under them.

Jesse Robertson-DuBois intends to lease the land from BlueWave and make the farm the year-round home for his livestock, the fencing and barns that come with it a plus. “As a non-land-owning farmer,” he writes, on Four Star’s website, “the opportunity to secure a long-term lease …would be a game changer. It’s not just the dual-use of the land, but of the project’s infrastructure as well.”

So maybe this grass farmer can make a go. But what of the next deal, and the next, and the next?

“Big solar wants it all,” said Beddall. “Floodplain land, APR land, Chapter 61A — and they have legislation to get it all. They are taking away our land one field at a time.”

Finally, there’s the problem of destroying indigenous cultural land and burial sites. Melissa Ferretti, president of the Herring Pond Wampanoag Tribe said, “Sacred sites are destroyed or threatened without adequately consulting us and violating our indigenous sovereignty.”

Though most of these sites are unmarked and buried under layers of earth, there are laws to protect them but, says Graveline, “They get around that by not making public what’s discovered, like the skulls and femurs found during the digging of the Route 2 bypass in Greenfield.”

But it does beg a question or two: There are thousands of unmarked burial grounds all over this country, not only Native Americans, but the graves of slaves, Chinese workers who built the railroads during western expansion, even the mass graves of mental patients on a hill overlooking the region’s Mill River.

Since it could be argued that the deaths of our more prominent (white) citizens were historically handled far more delicately, and since the vast acreage set aside for the graves of such would collectively surpass the land mass of any small nation, is it time to discuss building solar farms over cemeteries? That may, of course, offend loved one’s sensibilities and briefly disturb the eternal “rest” of those six feet under, but the overwhelming number of graves who haven’t been visited by anyone in centuries is staggering.

Ahh, the dead. Blithely ignorant of climate catastrophe, lost habitat, revenue streams, the insect apocalypse, and the “irresponsibility” of towns not taking advantage of financial windfalls. The living should have it so good.