Vitek Kruta was born in what is now the Czech Republic, trained in visual arts, including theatrical and architectural design, and worked for 10 years in Germany “restoring old castles and churches.” After moving to the States, he told me recently, “I rarely had the opportunity to show people what I do, because there’s not too many castles around here. So this was a perfect opportunity to just dive in and do it with a free hand.”

By “this” he meant the 19th-century mill building on Holyoke’s Race Street, fronting one of the city’s industrial-era canals, that’s now home to Gateway City Arts. The cultural hub almost died last year, a victim of the pandemic, but is now coming back to life. For Kruta, the whole building, and most recently a thoroughly renovated performance space, has become his canvas.

The theater, for small-scale performances and concerts, is the latest rebirth in the complex, which also houses a restaurant-bar, a small art gallery, work spaces for artists and entrepreneurs, a courtyard beer garden, and a 500-seat performance venue.

When the pandemic shuttered everything last year, Kruta and his partner, Lori Divine, were forced to lay off most and eventually all of their 40-person staff. They hunkered down, surviving on pandemic-relief grants and private contributions, trying to stay afloat, but eventually looking for a buyer for the two-building facility. Things turned around last spring, when music promoter DSP Productions was contracted to take over the management and programming of the large performance space for live music and other events.

“That has changed things,” Divine told me as we sat in the all-but-finished theater space last week. “It’s allowed us to feel like we can make it.”

Something uplifting

Making it includes upgrading and reopening GCA’s various entities one at a time, but it certainly doesn’t mean taking half measures. The redesigned theater, once a bare floor and empty walls, has become a marvel of Art Deco design.

A sparkling mini-proscenium with a with a blue curtain fringed in gold and flanked by faux-marble columns, has replaced the makeshift stage of previous productions. The arch is a gold-and-silver lattice of feathery contours sculpted from aluminum flashing, centered by a sunburst.

A sparkling mini-proscenium with a with a blue curtain fringed in gold and flanked by faux-marble columns, has replaced the makeshift stage of previous productions. The arch is a gold-and-silver lattice of feathery contours sculpted from aluminum flashing, centered by a sunburst.

“I love the era of Art Deco in the late 19th-early 20th century,” Kruta said. “Such a big era of theaters and entertainment.” He recalled that Holyoke once boasted six major theaters, of which only the Victory, currently being resurrected by the MIFA organization, remains. “It was an amazing city —the first designed industrial city in the country, and at one point the richest city per capita.” His designs in this room are a nod to that history, and to Kruta’s urge to create “something uplifting” to greet theatergoers as they enter.

A suite of murals adorns one wall, a romantic trompe-l’oeil view through painted arches onto a silvan lake at sunset. “Theater is an evening thing,” Kruta explained. “Before performance, you come in and the sunset is happening, it’s very tranquil — light of the golden hour.”

The theme is extended to the bar on the other side of the room, where a cloudy moonscape lends a late-night feel.

How long did it take Kruta to execute it all? “The right answer is whole life, and four weeks.”

The space has been named the Divine Theater, “in honor of my family,” Divine explained, “because they were so supportive of what we were doing here, and without that encouragement I’m not sure we would have made it.” She hastened to add that it wasn’t her idea. “When the staff came to me and told me they were naming it the Divine Theater, at first I said, ‘No no no, I like to remain anonymous.’ But I feel very moved and proud. My parents loved the arts, and this would have made them very happy. And I just think it’s gorgeous.”

The space has been named the Divine Theater, “in honor of my family,” Divine explained, “because they were so supportive of what we were doing here, and without that encouragement I’m not sure we would have made it.” She hastened to add that it wasn’t her idea. “When the staff came to me and told me they were naming it the Divine Theater, at first I said, ‘No no no, I like to remain anonymous.’ But I feel very moved and proud. My parents loved the arts, and this would have made them very happy. And I just think it’s gorgeous.”

The wordplay, Kruta said, was irresistible: a divine theater. The featherlike ornamentation of the proscenium “is like angels’ wings.” For her part, Divine finds Native American resonances in those feathers.

Doing it slower

Creating Gateway City Arts has been a decade-long labor of love — with the labor sometimes outweighing the love. Since the couple purchased the property in 2012, Kruta said, “Simply bringing it up to code has been a major construction project. During this time we learned a lot. It was as if we graduated from business school, and engineering, and architecture, and home design, and material design. Also, little by little, we learned about Holyoke, its history and architecture, and started to get to know the community, the people. It was quite an exciting time.”

It wasn’t their intention to create an arts complex, Divine said. “We were looking for an art studio for Vitek. He was working in his house in Holyoke and had outgrown it. We found out this building — actually two buildings — was for sale, really reasonable. We fell in love with it. We didn’t know what we were going to do with the building, but we just loved it. But after investigating what it was going to cost to bring it up to code, we walked away from it. We kept walking away and kept coming back and finally said, ‘Oh hell, let’s just do it.’ We should have done a little more research,” she added, laughing. “It was a nightmare at first, and very expensive.”

Ten years ago, Race Street “didn’t look like it does now,” Kruta recalled. There was no sidewalk on the canal side, just broken concrete. “Then the city started to build the Canal Walk, and for seven or eight months we were in the dust bowl. In the Beer Garden, every five minutes you’d be wiping down the tables.” But the municipal investment in urban restoration helped GCA become an arts magnet in a long-neglected city.

“The pandemic really did us a favor,” Divine admitted. “It slowed us down.” They’ve received three pandemic assistance grants, “and that’s allowing us to go ahead, but slowly. We’re doing what we can afford to do.

“We had so many ideas,” she continued. “We said, ‘We’d love to do this and this and this,’ and we did, only it cost us, and everyone was burned out and exhausted. Now there are only six of us, and we’re all doing everything, everyone pitches in and does what they can. Hopefully we’re smarter now, and we’re doing it slower.”

Two years ago they were joined by Dave Blood and Mauro Brito, refugees from California without whom, according to Kruta, “we would not be able to exist at all. They are Renaissance people, they can do so many things.” Among other things, they are the bakers who operate GCA’s smaller eatery, the Famous Café. Blood is “a genius who can also handle all the technical stuff,” Kruta says. Brito sewed the curtain in the Divine Theater.

Two years ago they were joined by Dave Blood and Mauro Brito, refugees from California without whom, according to Kruta, “we would not be able to exist at all. They are Renaissance people, they can do so many things.” Among other things, they are the bakers who operate GCA’s smaller eatery, the Famous Café. Blood is “a genius who can also handle all the technical stuff,” Kruta says. Brito sewed the curtain in the Divine Theater.

Two key staff members, Rachel Keizer and Lindsay Hart, laid off when the money ran out, have returned. And Kevin Tracy has just been hired as house technician for the theater.

Tracy is the founder/director of Ghost Light Theater, whose home base was at GCA before ghost lights went up in all the theaters. “Mostly I’m making sure the sound and light setup is in good condition, but I have a lot of creative input as well,” he told me recently. The facelift makes the theater “feel more dramatic. When you come in here you should feel like you’ve stepped out of the regular world.”

Ghost Light, he said, is also reviving in the new space. “Our workshop series will be back and we’re planning on a full show in the near future.”

Faking it, making it

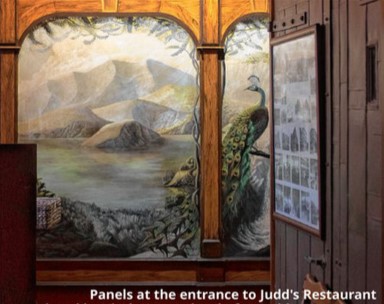

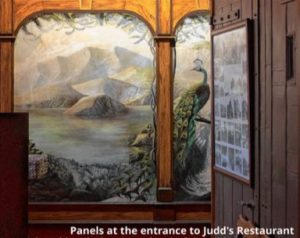

Across the lobby-cum-gallery from the theater is Judd’s Restaurant and Bar, which reopened early this month. It’s named for the building’s original occupant, Judd Paper Company. The current reduced menu — cooking is another of Kruta’s talents — includes Czech staples such as paprikash and goulash, plus exotic flatbreads and a cluster of sweets. The interior echoes the theater’s turn-of-the-century feel, an Old World bistro done out in brick and old wood — except the brick and wood are both fake.

“None of this is natural wood, it’s painted to look like natural wood,” Kruta said proudly. “This is part of my Old World training.” In addition, he assured me, “It’s all recycled materials, in the theater too. It’s all hand-made and custom-made from leftovers.” The original brick walls — the universal cladding of New England’s Industrial Age factories — were in such poor condition that he recreated them in paint. Both of these forgeries are so realistic-looking that you have to touch them to be disillusioned.

“None of this is natural wood, it’s painted to look like natural wood,” Kruta said proudly. “This is part of my Old World training.” In addition, he assured me, “It’s all recycled materials, in the theater too. It’s all hand-made and custom-made from leftovers.” The original brick walls — the universal cladding of New England’s Industrial Age factories — were in such poor condition that he recreated them in paint. Both of these forgeries are so realistic-looking that you have to touch them to be disillusioned.

Somewhere in the future, the couple imagines the various components of this multifaceted operation as independent employee-owned enterprises. For now, though, it’s one step at a time after being one step away from giving up.

“We’re only going to do what we can manage,” Divine said. “A year ago we weren’t making it. Even before we shut down we were losing money. But now, we feel like there’s hope.”

Photos by Carol Lollis & Chris Rohmann

Chris Rohmann is at StageStruck@crocker.com and valleyadvocate.com/author/chris-rohmann