Before the cellphone contagion, what games did families play during long trips in the car? Spotting license plates from other states or guessing the names of passing motorists kept our cherubs amused,: “Oh, that’s a Fester for sure!” These days, you could keep the young’uns involved from here to Provincetown by having them shout out every time they saw a pot shop.

There are more than 160 retail marijuana dispensaries in the state – including 30-plus in the Pioneer Valley – and more on the way. Once feared by many, the products sold now are as legitimate as a hot dog stand. And probably healthier.

It’s been five years since Massachusetts voters gave the nod to legalize an ancient plant that many of them had enjoyed all along. But to no longer have to hide this behavior while tacitly supporting the D.A.R.E program was a big ol’ breath of fresh air. Who can forget the mile-long line in the pouring rain the day NETA opened for business in Northampton, the joy on rain-pelted faces, the soaking-wet vibe of liberation, as friendly cops directed traffic on Pleasant and Conz streets, not the least bit interested in the contents of that bag you were daintily carrying out of the place.

“Decriminalized in ‘08, medical marijuana approved in 2012, adult use in 2016 — three for three,” says Northampton attorney Dick Evans, who carried on the fight for legalization for 40 years and helped write the bill. “I was at a rally in 2010 and said, ‘Yeah, right.”

“I think the big factor was that voters were given the opportunity, and the Legislature heard them,” Evans says. “The initiative process worked just like it was supposed to. Lawmakers turned their backs (on legalization) until they couldn’t.”

“But at 11:59 on Dec. 31st they said hold on, and suspended it until they could do major surgery. (Senate President) Stan Rosenberg appointed an important joint committee; thing was signed into law June 17, 2017,” Evans continues. “Lot of significant changes. The good news is they didn’t touch personal freedom. The most detrimental was giving municipalities carte blanche to charge fees that the hardware store doesn’t have to pay. They got away with unfair exploitation.”

Amherst writer Terry Franklin, a longtime activist and an organizer of Extravaganja, one of the longest-running marijuana celebration/reform rallies in the country, thinks it took too long to get where we are today. “I thought it happened too slow,” he says. “There was a big push in the 1970s — I thought it was going to happen then.”

Franklin likens those who stuck their necks out way back when, like UMass Amherst’s Cannabis Reform Coalition and its three-decade battle to get marijuana on a ballot, as “Christianity in the Roman Empire.”

Pot corporations and the black market

But, for all that, is this what people envisioned — multi-partnered corporations sprouting up like McDonald’s, collecting over $2 billion in gross sales during its first four years, yet along the way offering no clear path for the average citizen, let alone minority, to get their foot in the door?

“I might have been a little naïve hoping for something else,” Franklin says. “Crony capitalism, with the Tea Party and Occupation movements, had been attacked from the left and the right. Now crony capitalism is what we’ve got, with the possibility for total corruption. It’s a very high economical barrier to enter. Police chiefs involved in the drug war — now they’re consultants. Big-moneyed people with vested interests. I voted for it to keep people out of jail.”

The law allows your 21-or-older self to grow six to 12 plants in your house, with the understanding that it’s against the law to sell the excess. Of course, in order to smoke the yield of all those plants, you’d have to be Cheech, Chong, the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers and half the stable at Death Row Records. In other words, if you know what you’re doing, there’ll be stuff left over, and plenty to sell.

Some may say that the “underground” commerce that ensues cuts into the profits of pot shops, which, nonetheless, keep sprouting like crocus in March. Northampton alone now has eight dispensaries, the most recent one, Enlite Cannabis, whose CEO Matt Yee told the Gazette that his “biggest competition is the black market.”

Yes, the “black market” guy down the street is still going strong and receiving visitors at all hours as usual. But, due to the collective power of state-sanctioned dispensaries, the guy down the street is still an underground entity, just as before, most not willing to share real names or locations, the familiar jolt to the heart of a loud voice at the door with a warrant an unwelcome memory.

“I’ve got enough stuff for the rest of my life,” said longtime hill-town grower Tukka-Bear, 41. (Not his real name) “My customer base took many years to build. They smoke my stuff and won’t take anything else.”

“They tried to over-regulate it; they wanted it to go even further,” says Franklin. “The way it should have worked: grow as much as you want. If you’re growing more than is allowed you are presumed to be selling, which presents a problem for the conglomerates. People get a license and go through hoops and get a quasi-monopoly — they’re gonna have incentive to go after home growers. I’d be surprised if they pushed to eliminate home grown, but if it’s politically possible they’ll do it.”

“My advice?’ says Franklin. “Get the cheapest stuff you can find, black market or no.”

Weed’s connecting power

This past August a little Amsterdam came our way with the arrival of the Holyoke Cannabis Cup, an all-day where dispensaries and home-growers alike took home trophies. But you had not been in the midst of such diversity since the late 1960s or when Sen. Ted Kennedy’s body lay in state in Dorchester Bay, a right-down-the-middle black/white/brown/young/old/disabled split of smiling faces, grooving to the same hip hop, the same metal, bonding over something as simple as marijuana.

And nobody, believe it or not, was afraid or suspicious of anyone. You repaired with like-minded brethren to a patch of fenced-off grass over in the far corner clearly marked SMOKING AREA, and sat with your back leaning against a chain link fence, where the conversation was funny, relaxed and ironic, taking place not 10 feet from Police and Security. And you overheard one cop chuckle at the idea of fights breaking out: “With this bunch? Unlikely.” Friends were made, many from neighborhoods the other had never set foot in.

“It’s SO diverse,” says Evans, of weed’s connecting power. “Why don’t people realize? It brings us together. If there’s anything we need in our times, it’s this.”

As for the main point made during the fight for reform, Evans said: “Revealing the fraud, the scam that was prohibition. They used to say that it caused Black men to rape white women, which led right to Nixon’s Drug War, the greatest rhetorical triumph of the 20th century, the conflation of the use-and-abuse scam that sustained the drug war for so many years.”

“After our success in 2016, no one’s arrested, no one’s kicked out of college, no one gets fired. Voters stopped it. Legalization has been a huge success. So many new jobs, so many buildings repurposed. Holyoke’s (Alex) Morse was the only elected public official to (declare his support) early and look what he’s produced for Holyoke’s economy.”

“The disappointing part is that it’s so hard to get into, so hard to open the commercial benefits to the minorities so affected by historical injustices. So many darn rules — 200 pages of regulations! People pay rent on empty spaces for years. We, for political purposes, put these things into the initiatives to assure voters who were on the fence,” says Evans. “It’s time for re-assessment. People wanted strict control but we controlled marijuana like it was plutonium.”

Evans hosted a riverfront victory celebration in October for members of the UMass Amherst Cannabis Reform Coalition, who fought a 30-year battle for cannabis reform and sponsored Extravaganja. The event, a “Celebration of Mission (truly) Accomplished,” marked the end of an era as CRC’s last president, Claire Walsh, entrusted CRC papers and records to Carol Connare of UMass’ Libraries Special Collections and Archives. “You were one of first to emerge during the dark days of the Drug War, when advocacy for reform was risky,” wrote NORML’s founder Keith Stroup in a letter read to the crowd. “People of Massachusetts and the country owe you a huge debt for helping to consign prohibition to the ashcan of history.”

“It’s a new world and a better one,” Evans smiled. “I mean, I’ll give a jar of my crop to a friend and put my NAME on it. Never had I dreamed.”

The ‘grey’ market

It’s not the backyard hobbyists that worry the dispensaries, it’s the competition from sophisticated full-cellar operations, the so-called black market. “I don’t like to call it the black market,” says Evans. “More like a grey market. Taxation is what makes it competitive. Most in the grey market want desperately to go legit.”

“Growing saved my life,” says Tukka-Bear. “I was a ruthless alcoholic, in and out of jail, rehab, hospital. I told my family I wanted to grow weed; in junior high I was growing it out in a field. ‘If you stay straight we’ll buy you a $400 grow-light system,’ they said. It gave me that little spark of hope to get out of bed, the only thing that gave me happiness during the first year or two of sobriety.”

His talent for the sport kicked in from there. Also the swagger.

“Eighty to ninety percent of home-growers throw in the towel,” Tukka- Bear says. “They buy all the equipment, grow a round or two and it doesn’t come out like they say in the magazine. You can read books all day about flying helicopters, doesn’t mean you can fly helicopters. The key? Being able to correct problems before they become problems. I’m a master grower — if the pump breaks I can fix it. I get way better weed than anyone.” He’s had offers to move to California and fix an outdoor operation that was failing. But he likes it here. He has applied and hopes to get a Tier 1 license, “in months instead of years.”

As for former grower/dealers who endured harassment and prosecution and now find employment with dispensaries, another Hilltown home-grower scoffed: “Me and my bros been keepin’ it on the DL underground for years with top strains, unlike this other clown mascot who wants the fame.”

“And they’re fudging stats and not asking about contaminants,” said Tukka-Bear. “No one’s ever gotten sick with my stuff.”

“The stigma and all that propaganda bullshit is starting to go away,” says Tukka-Bear. “It’s socially accepted now. Eighty percent wouldn’t have admitted using it only 10 years ago.”

Of his life, he said, “All I do is grow, trim and walk the dog. No one’s had a productive system for 16 years without being shut down. I try not to be cocky but I’m the guy who’ll blow any dispensary out of the water.”

Swagger comes with the territory, fueled by the hip-hop that accompanies all that trimming. “Big Pharma’s trying to get their claws on it, but they don’t know what they’re doing. 18% gets you just as high as 30% even if it tastes like dogshit.”

The future

Tukka-Bear, like Evans and Franklin, believes that the pot laws will evolve to enable the average person with a business plan to get a loan and open shop, and that there’ll always be a place for the dedicated home grower.

He expresses little resentment for the dispensaries or the law that gave rise to them. “I knew it was just going to allow major corporations to come in and push shit. I wasn’t mad, I wasn’t disappointed. People in it just for the money never produce anything worthwhile. People who do it for love … if you have a job you love, you never work, even through 14-hour days.”

“But the important thing is that not one person is getting arrested. As long as you’re not f—ing with the IRS, you’ll be OK.”

As for those pesky federal laws that still classify grass as a controlled substance, Rep. Nancy Mace, a Republican from South Carolina, has filed a major federal reform bill and may have the votes.

But for all those years of home invasion by law enforcement and stiff sentences handed out to mere users, there were plenty of law-abiding folks who were decades late to the pot party, and only checked in when the law got overturned.

Jane, of Gloucester, and husband Frank, both in their 60s, tell the classic tale about managing to stay away from weed until 60s-type pain set in. “Frank had a hip replacement,” she said. “The only thing that gave him comfort was a gummy. He takes one every single night and can’t imagine NOT taking one.”

Neither of them smoked cigarettes so “wacky tobacky” was never that alluring. “Maybe Frank tried it as a youth, but 30 years together and we’ve never used marijuana once. Now it’s daily, or should I say, nightly. It wasn’t something we’d seek out; neither of us would take something without knowing what’s inside it,” says Jane. “Now I’ve got it in a form I can trust, and I can speak with someone.”

The semi-retired couple frequent a dispensary in Gloucester but purchased their first edibles at NETA in Northampton, a definite leap of faith for those who never spoke the language of cannabis.

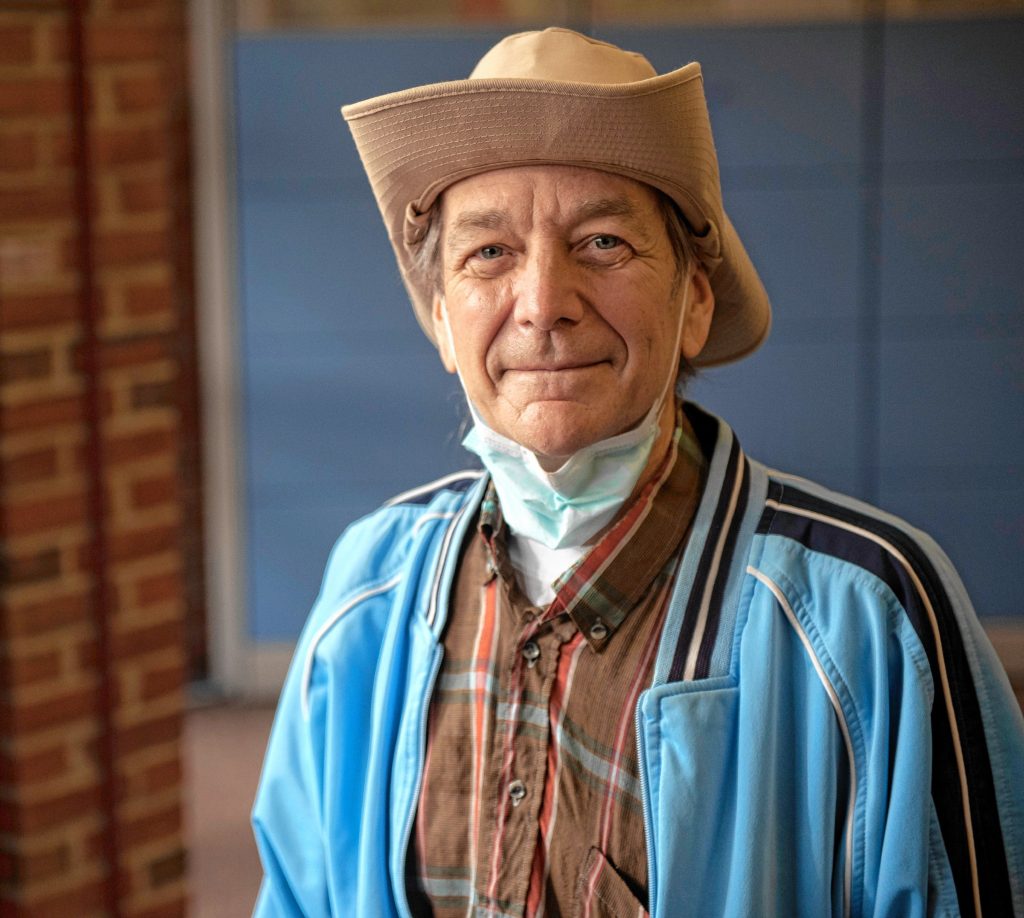

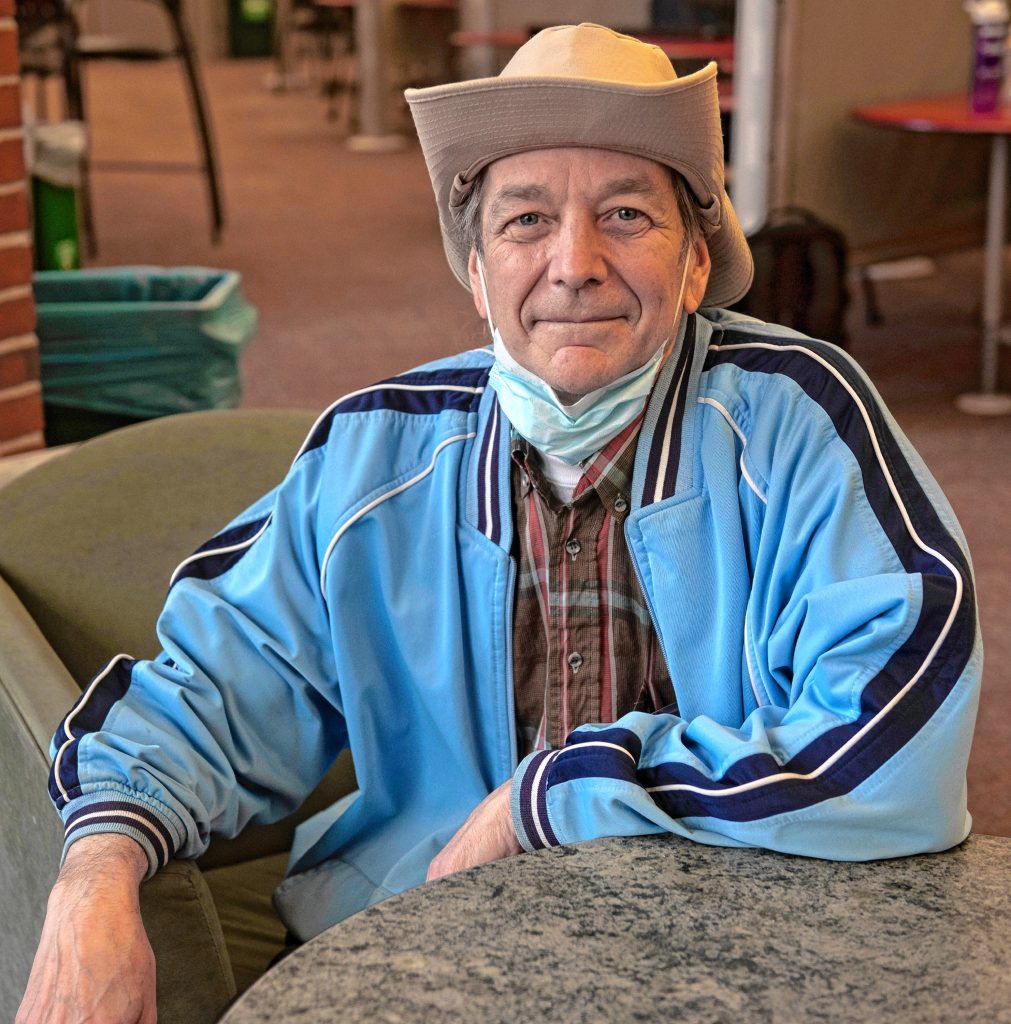

And that brings us to the cosmic case of Jim Mias of Leeds, 67, the well-known youth baseball coach, now retired, who rides his low-tech bicycle year-round. In the early days of legalization, when only four pot shops existed in all of New England, including one in Leicester, Mias was out on Glendale Road, just riding, when he found himself on Easthampton’s bike path right under the sign for INSA.

“Oh, I think I’ll stop and get some edibles,” he said to himself, and tossed the gummies into his handlebar-mounted basket and pushed on, to Northampton, where, shockingly, there was no line at NETA, so he went inside and got a couple more. “Then I took a couple,” he said. “That’s when it occurred to me that, ‘Jeez, there’s that new place in Amherst, RISE.’” Once there, he told staff: “You won’t believe this, but I’ve just purchased edibles in all three western Mass pot shops in the same day! It didn’t make much of an impression on ‘em.”

Later that day, having to visit his sister in Spencer, he threw the bike in the car, simply anticipating that he might get another ride in. “Then it occurred to me that Breezy Gardens in Leicester was nearby. Back then you had to park far away and get a shuttle to the place. Screw the shuttle — I’m on a bike!”

At day’s end, Mias had inadvertently done business with every pot shop in Mass in one day. In earlier times, Jim would have that basket stocked with a 12-pack of beer. “The gummies are slow releasing. No doubt in my mind it lends itself to creativity.” His numerous wood sculptures along the Mill River may provide evidence of such.

And former leftfielders now selling him pot over the counter? Good grief.