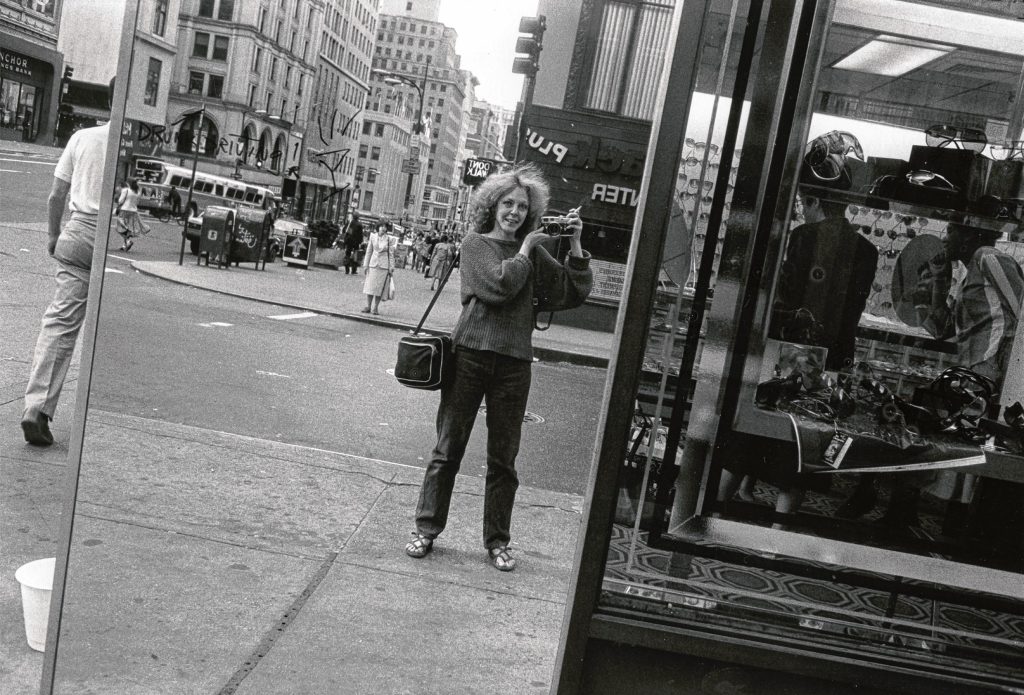

When documentary photographer Jill Freedman died in 2019, she left behind a huge body of work focused on people living on the margins in urban American, on protestors against poverty and war, and on cops and firefighters doing their intense work day after day.

“I consider her one of the great street photographers,” New York gallery owner Steve Kasher, who represented Freedman’s work, said following her death at age 79. He called Freedman “the true heir of Weegee,” the famous New York crime and street photographer of the mid-20th century.

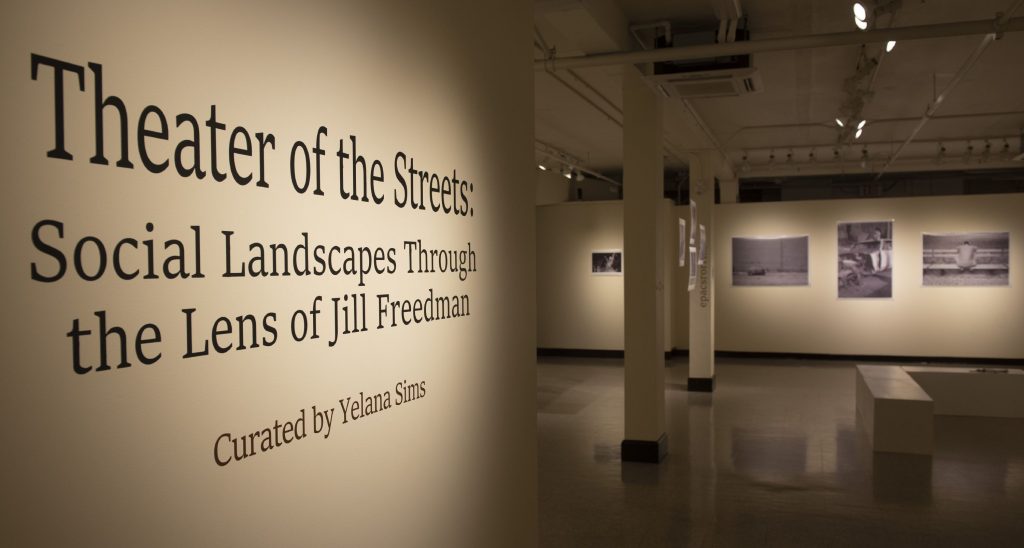

Some of her work, which is part of the permanent collections of The Museum of Modern Art and other museums, can now be seen in “Theater of the Streets: Social Landscapes Through the Lens of Jill Freedman,” a new exhibit at the Augusta Savage Gallery at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

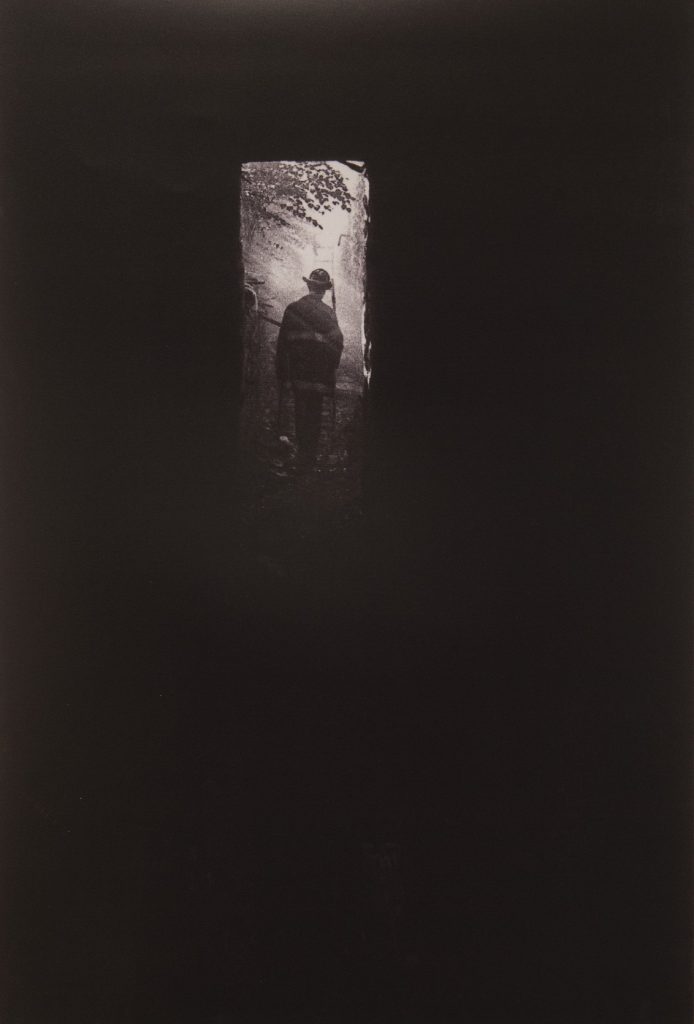

From iconic shots of a gritty New York City in the 1970s, to portraits of the Poor People’s Campaign in 1968, to an image of firefighters removing a body from the rubble of a collapsed hotel, Freedman’s black and white photos, as exhibit notes put it, “forced viewers to confront unfamiliar and uncomfortable scenes.”

The display, divided into four sections, has been arranged by graduate students from the UMass Public History program, the Department of History, and the W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies. Yelana Sims, a doctoral student in Afro-American studies, served as curator.

Sims said the exhibit traces its origins to research that Traci Parker, a UMass professor of Afro-American studies, was doing in 2020. Coming across some of Freedman’s images, Parker got in touch with the photographer’s estate in northern New Jersey, Sims said, and “They started talking about ways of getting Jill’s work some more attention.”

Parker and Marla Miller, formerly head of the university’s Public History program, then hosted a winter intercession class in Dec. 2020/Jan. 2021, in which Sims and eight other students planned how they might exhibit Freedman’s photos at UMass. Alexia Cota, interim director of the Augusta Savage Gallery, was interested in staging the show, and Sims went to Freedman’s estate last summer to look at additional photos in the collection.

Choosing what to show was a huge challenge, Sims said: “There were so many powerful images.”

Freedman, born in Pittsburgh in 1939, graduated from the University of Pittsburgh in 1961 with a degree in sociology. As the bio on her website notes, she was uncertain what she wanted to do with her life and spent a few years as an itinerant singer. She later moved to New York and got a job as an advertising copywriter — and then, she said, “One day I woke up and wanted a camera.”

After teaching herself photography, she quit her job as a copywriter in 1968, furious over the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in April. She went to Washington, D.C. to document the Poor People’s Campaign, a march to the capital — some 3,000 people established a tent encampment on the National Mall called “Resurrection City” — that King had called for to bring attention to widespread poverty and inequality in the U.S.

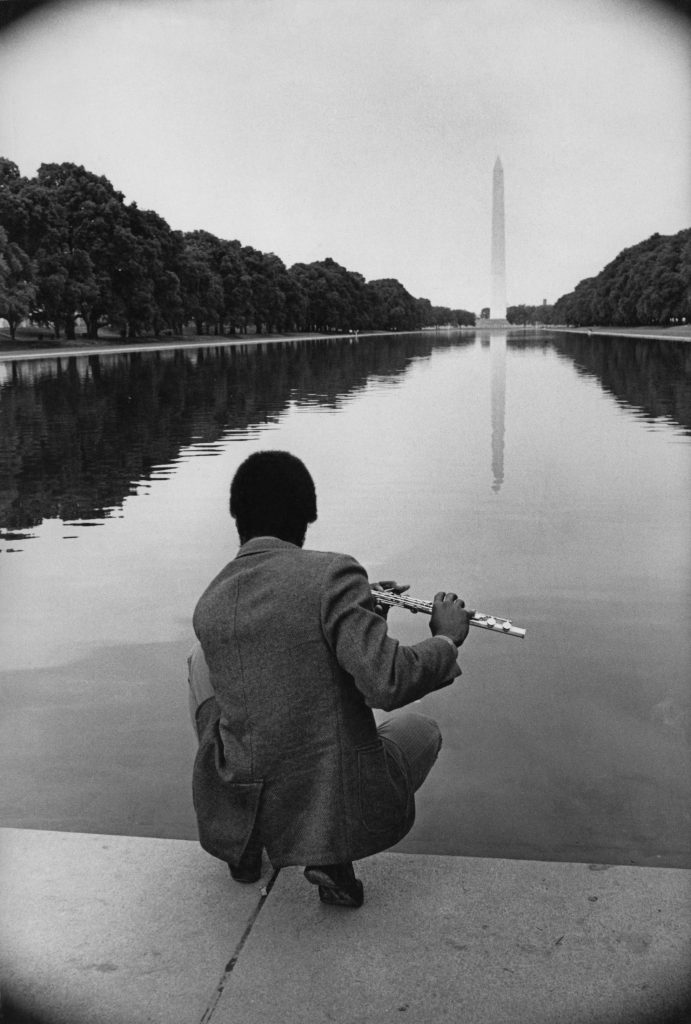

The UMass exhibit includes a number of images from Freedman’s time there, predominantly of people of color: singing together, holding signs, marching in protest. In one, a lone man crouches by the reflecting pool of the Lincoln Memorial, the Washington Monument in the distance, and plays a flute.

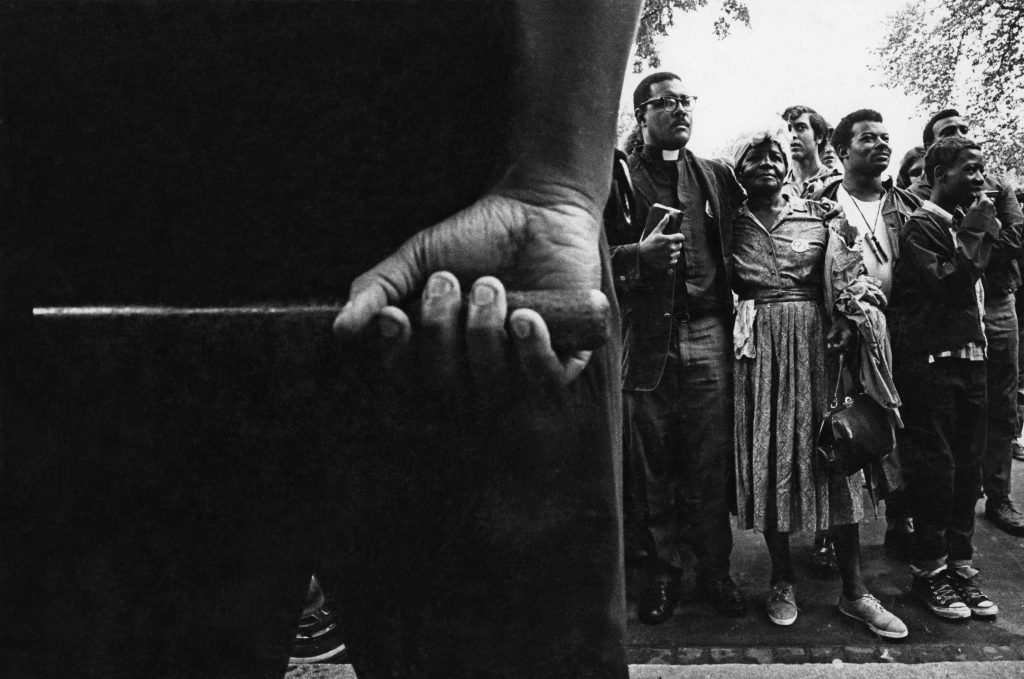

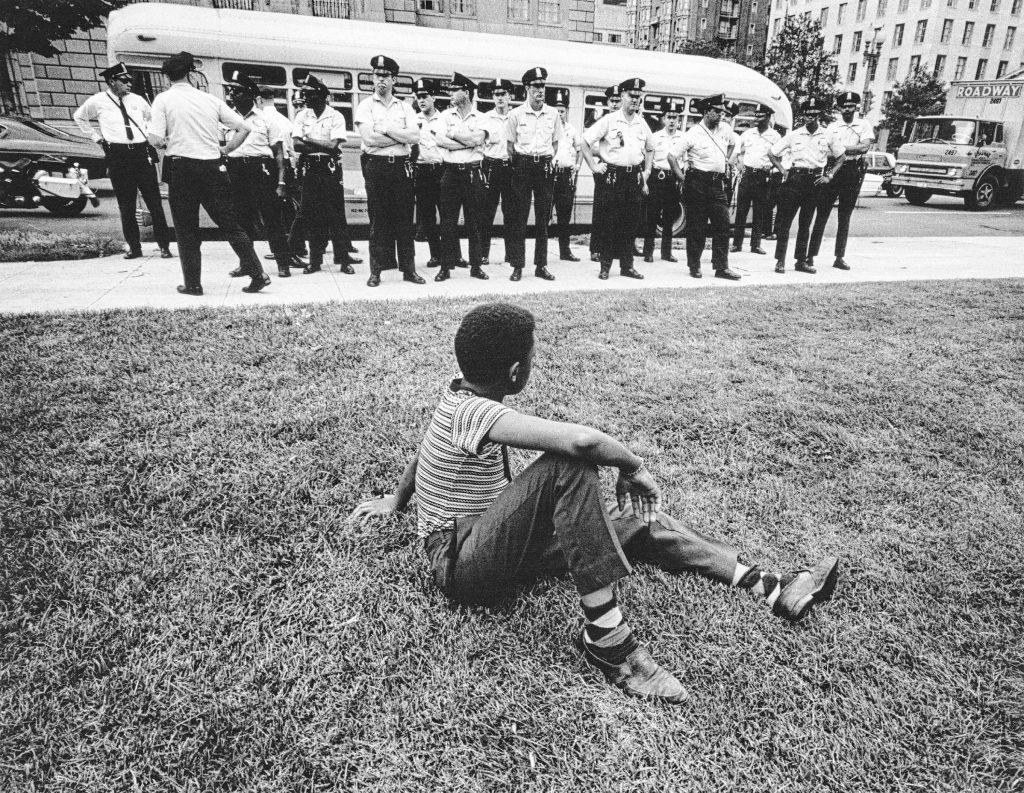

Other images appear more ominous. In one, Freedman frames a handful of residents of Resurrection City against a closeup view, shot from behind, of a policeman; all you can see of him is the back of his upper legs, some of his back, and his right hand, curled around a baton.

Freedman also chronicled the unrest in America in that era over divisive issues such as the Vietnam War. Two shots from New York City in 1967 offer a dramatic contrast, with one showing mostly Black protestors marching against the war. Some hold signs quoting boxing great Muhammad Ali’s explanation of why he refused to be drafted to fight: “No Vietnamese ever called me [racial expletive].”

In another 1967 march, called the “Patriot Parade,” white demonstrators walk down a New York City street waving American flags, and one man holds aloft a sign saying “Burn Yourself Not Our Flag.”

An unvarnished New York

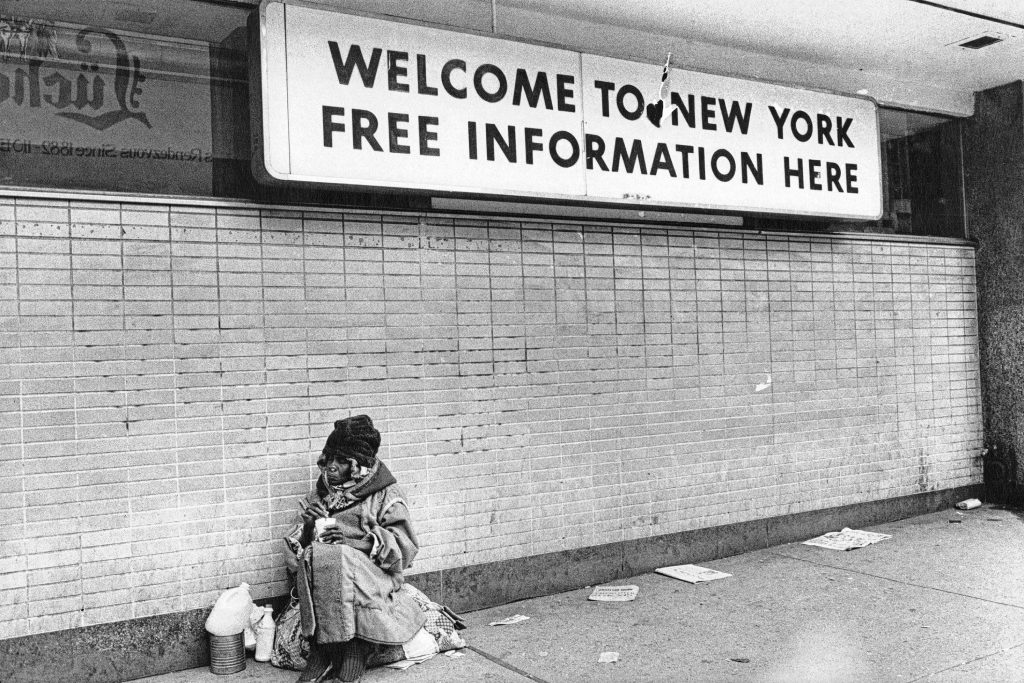

Some of Freedman’s most powerful images, collectively labeled “Cityscapes” in the UMass exhibit, focus on the rough edges of New York City, her longtime adopted home (she also lived for a time in South Florida). One of the most striking is from 1976, in which a homeless woman in Times Square sits on a sidewalk with a few ragged possessions, underneath a sign that reads “Welcome to New York/Free Information Here.”

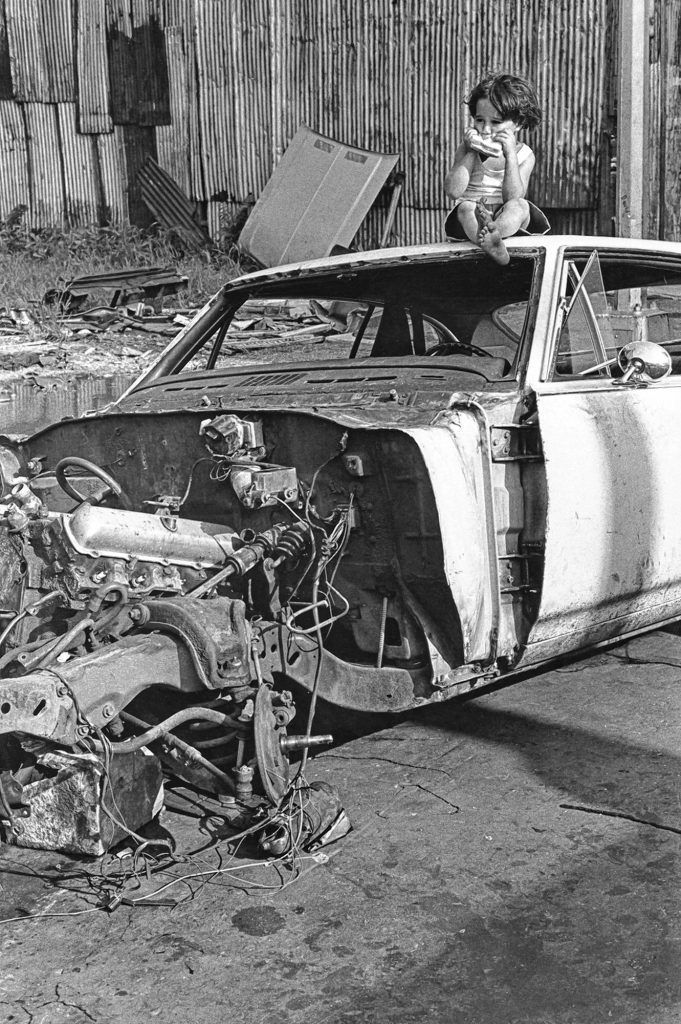

In “South Bronx Dining,” also from 1976, a young, barefoot child eats a sandwich while seated on top of a wrecked car; piles of junk and a ramshackle wall of corrugated metal frame the image’s background. In an image from 1986, an elderly woman walks past a grimy adult book store that advertises 25-cent “Peep Shows.”

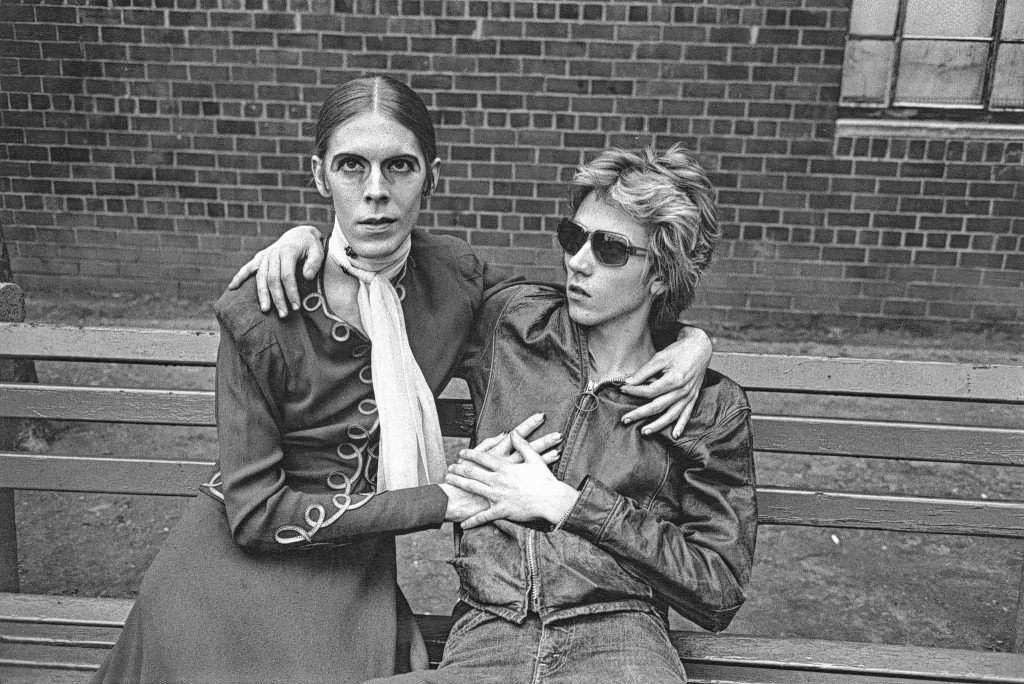

Freedman also documented some of the city’s alternative communities decades before LGBTQ became a well-known acronym, photographing a gay couple in Greenwich Village.

“She really showed a lot of compassion for people,” said Sims.

As exhibit notes put it, “Her works show a deep affection for the city and a commitment to chronicling its changes,” even as Freedman came to lament much of the gentrification of New York.

Freedman profiled other close-knit communities. She earned the trust of New York firefighters, who let her stay in their firehouse, and then police officers who let her join their patrols (she published books based on both of these efforts, as well as one on her time in Resurrection City).

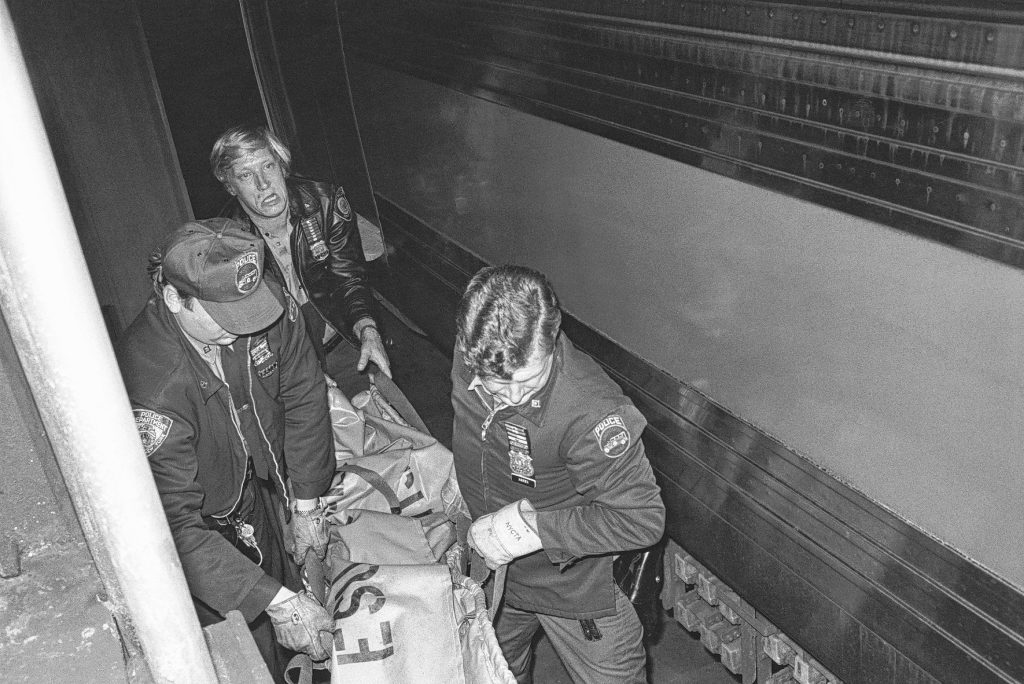

Her shots of cops and firefighters, dubbed “Powerscapes,” show them in many aspects of their work: making arrests and frisking people, clambering into burning buildings, carrying dead bodies. In one shot, two drained-looking firemen stand with unlit cigarettes dangling from their mouths. In another, two teenage girls stick their tongues out at a cop in a police van; you can’t quite tell from the angle of the photograph, but there’s a suggestion he’s amused.

“I hate the violence you see on TV and in the movies,” Freedman once wrote about her work photographing police. “I wanted to show it straight, violence without commercial interruption, sleazy and not so pretty without its make-up.

“I also wanted to show the tenderness and compassion of the good guys,” she wrote, “the ones who care and try to help. Moments of gentleness, good times as well as bad.”

“Theater of the Streets” runs through March 4.

Steve Pfarrer can be reached at spfarrer@gazettenet.com.