Just under a couple years ago, Nayana LaFond, like so much of the world, was stuck at home, sheltering from COVID-19. The Athol artist, who until that point had mostly been a semi-abstract painter, was looking both to keep busy and maybe take on a new project.

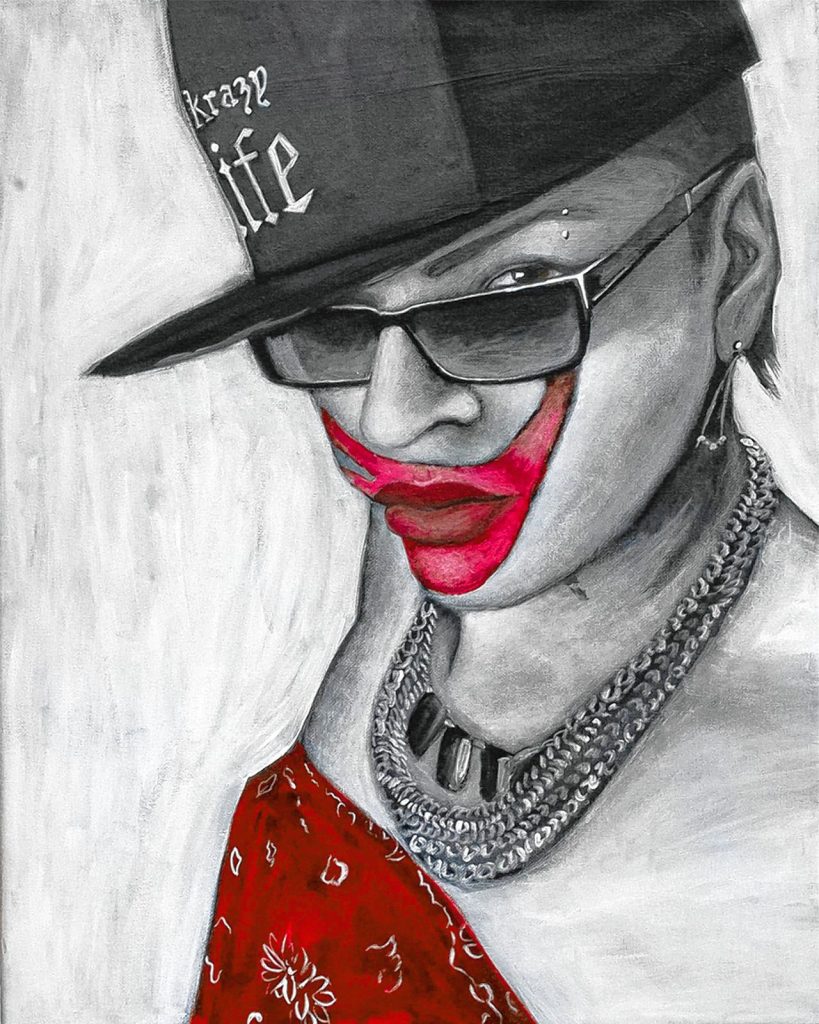

In early May 2020, LaFond checked a Facebook site she knew, called the Social Distance Powwow, created in the early days of the pandemic by a group of Native American and Indigenous peoples to keep the community connected. She saw a selfie of a Saskatchewan woman named Lauraina Bear, a photo in which Bear wore red makeup to, as she described in a post, honor other Indigenous women who had been murdered or gone missing.

LaFond, whose ancestry is part Anishinaabe, Abenaki and Mi’kmaq, knew of what’s called MMIW — Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women — a movement that works to raise awareness of violence against Native women and girls. But the photo of Lauraina Bear made the campaign very real to her.

“I messaged her and said ‘I really love your image. It’s so striking — can I paint it?’ ” LaFond, who’s in her early 40s, said during a recent interview in her home. “And she said yes, and so I painted her portrait.”

That mostly black and white work depicts Bear with a red hand across her mouth and cheeks, with other lines of red extending above her left eye. And the dramatic portrait, in a way LaFond never expected, unleashed a tidal wave of additional work for her that has since been shown in galleries in the Valley, across the state, and in New York, Connecticut and Montana.

As she explains, after she posted a picture of her Lauraina Bear portrait to the Social Distance Powwow, some 3,000 comments flooded in. She received requests to do additional portraits, so she did one of a mother and daughter — “Natahne & Yana in RED” — and after posting an image of that to the Facebook site, more requests followed.

“I was thinking, ‘OK, I’m stuck at home, like we all are, I want stuff to paint,’ ” said LaFond, a 1998 graduate of Amherst Regional High School. said. “So I posted on the site, ‘I’ll paint you or your loved one in honor of this movement if you’ll send [photos] to me.’

“I thought I’d get a few more,” she said. “I got 25, and they all came with stories — ‘This is my cousin, this is my mother, this is my sister, this is what happened, we’re mourning.’

“I couldn’t choose one over the other so I said, ‘I guess I’ll just paint them all,’ ” LaFond said. “And they just kept coming — dozens and dozens and dozens.”

A personal connection

As of late March, she had painted 77 portraits, all in black, white and red acrylic paint, with about another 30 in the queue. Many are profiles of murdered or missing women and girls, but there are also portraits of survivors of domestic violence, family members and friends seeking to remember their loved ones, and activists working to try and stop the assaults.

Most of the portraits depict women with hands, usually red, painted across their mouths or faces (sometimes parts of their clothing or different parts of the body are in red). LaFond says the hand represents the voices of women being silenced — an image that came out of the MMIW movement. But she notes that in many Indigenous cultures, it’s also believed spirits can only see the color red, so a red hand becomes a means for spirits to identify the lost women and bring them home.

For LaFond, much of the outpouring of emotion for her project has struck a personal chord. She’s a survivor herself, having been stricken with leukemia in 2014 that forced her to have a bone marrow transplant. She went through a difficult marriage and is the mother of a daughter, Adelaide, who’s just turning 12. She’s had a long career in the arts that has been creatively satisfying but never financially easy, she says.

In fact, she has painted her MMIW portraits mostly for free — she gives prints to the people she’s profiled and has sold a few others to help pay for art supplies — because, she says, she believes in MMIW’s mission and doesn’t want to profit from other people’s loss. And, she adds, doing the work brings her a sense of peace and healing.

“I’m very lucky to be here,” she said. “I’m grateful, and I’m trying to channel all of that energy into positivity…. I like to think that all the crap I went through prepared me to do this kind of work, gave me the empathy to understand what these [portrait subjects] have gone through.

“For me it’s healing to do each one because I can put a little bit of the pain that’s in me into the painting,” LaFond said. “And I want to make sure my Indigenous community knows I’m doing this for the right reasons.”

A varied career

LaFond, who grew up mostly in the Valley and attended public schools in Amherst, Northampton, and Hadley, had a varied art career before getting involved in her MMIW portraits, which have taken up a good deal of her time the last two years.

She studied painting and photography in college before dropping her studies to work as a curator, including eight years at the Whitney Center of the Arts in Pittsfield. She also once ran an independent record label as well as a cafe, the latter in Turners Falls, where she was the “chef, bookkeeper, chief bottle washer and a few other things,” she said with a laugh.

She previously painted in color but switched to black and white, both because it was less expensive and because it better matched her general, more abstract subject matter, which in more recent years has touched on issues such as her own health struggles and social justice causes. She has also produced a series of COVID-themed paintings in the last two years.

“I kind of feel my whole life was set up to do this [MMIW] project, because I was already painting in black and white, although I wasn’t doing portraits,” she said.

LaFond says her income comes from a number of sources, including sales of non-MMIW artwork, speaking engagements, and disability payments. The notice she’s gotten from her MMIW portraits has also led to new commissions, such as an installation (she’s also a sculptor) she’s designing for the Fenway neighborhood in Boston. That MMIW-themed work is slated to be in place in May.

While she’s pleased with the attention she’s received for her MMIW work, LaFond is also a little concerned about being pigeonholed for it. “I appreciate being identified as a Native artist, but I would rather be identified as an artist,” she said. “I had a strong and varied career in art before I became involved” with MMIW.

Yet she also sees the importance in helping advance that cause. According to the MMIW movement, Indigenous women in Canada and the U.S. experience higher rates of domestic violence, including sexual assaults, than any other demographic, and in the U.S. two-thirds of those assaults are committed by non-Native people.

Advocates for Indigenous women point to a number of problems, including what they say is a lax attitude among law enforcement and government officials in certain places.

“It’s a belief system in some communities that Native people are disposable,” said LaFond, who says one Canadian woman told her she was afraid to go to her rural mailbox because several other Indigenous women had disappeared from the same community.

She also says there’s “a long history of Native people being conditioned to accept lesser conditions” in their lives. Her grandmother on the Native side of her family was given away at birth to a white family, she says, after her mother, originally from Canada, was jailed in eastern Massachusetts because she’d had an affair with a married man.

“Think of what that would do to a family and how that would trickle down through generations,” said LaFond, whose mother married the grandson of a onetime mayor of Northampton, Jesse Andre, who led the city in the late 1920s; the grandson “legally adopted me and raised me,” LaFond noted.

Given all that, LaFond says she’s excited that a gallery in Bozeman, Montana that featured her work in a group exhibit of Indigenous artists is now putting together a touring exhibit based on the show; it’s slated to travel across the U.S. and possibly up to Canada over the next few years. Her work will also be displayed in April in Five Points Arts Center, a gallery in Torrington, Connecticut.

She’s recently been asked about doing a comparable project for aboriginal people in Australia; she was preparing to talk to some of the project sponsors via Zoom to find out more.

It might mean adding more work to an already busy schedule, but she says she’s OK with that.

“I want to do as much as I can right now,” LaFond said. “The average life expectancy after a bone marrow transplant is 10 years. I’m feeling great and I think I’ll definitely surpass that, but the reality is none of us know. I want to make the biggest impact I can, so that when I’m gone … there’s something left behind.”

The Augusta Savage Gallery at the University of Massachusetts Amherst will exhibit some of LaFond’s MMIW portraits from Jan. 30 through April 28, 2023, and the gallery is currently collecting painting supply donations for the artist through May 5. Visit fac.umass.edu/Online and follow the link to Augusta Savage Gallery for more information.

Steve Pfarrer can be reached at spfarrer@gazettenet.com.