Code-switching is a term in linguistics that describes how people raised in two different cultures “switch” their use of language, and by extension behaviors, according to which milieu they’re in. These days, it applies particularly to people of color in a white-predominant society.

Dreams is a poem by Langston Hughes: “Hold fast to dreams/ For if dreams die/ Life is a broken-winged bird / That cannot fly.”

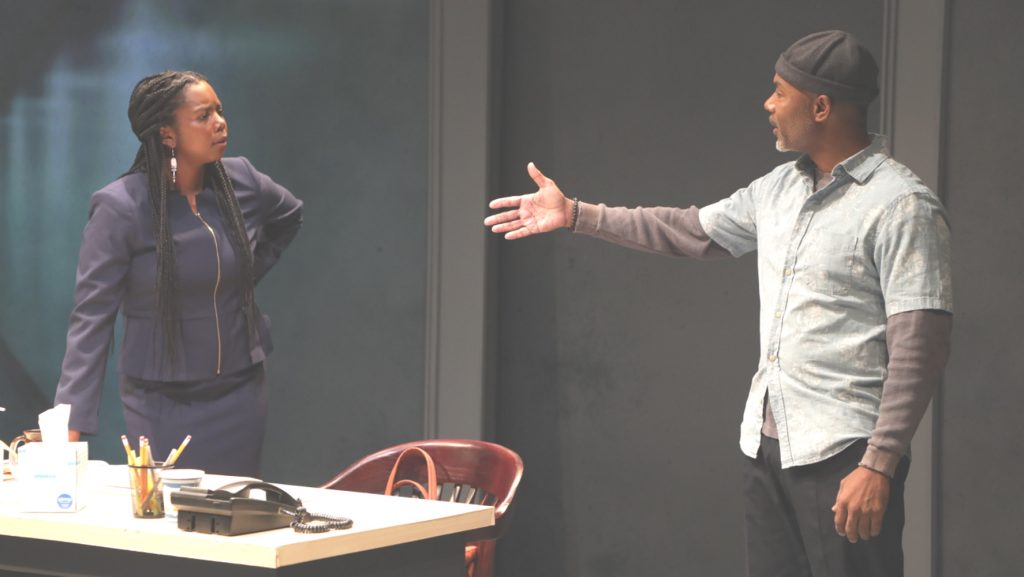

B.R.O.K.E.N code B.I.R.D switching is a play by Tara L. Wilson Noth that combines the two themes interleaved in her title. Its world premiere is playing in the Berkshire Theatre Group’s Unicorn Theatre in Stockbridge through this weekend.

The code-switching thread is embodied by Olivia, a Black lawyer married to a white lawyer. He’s a corporate attorney in a high-rise midtown firm, she works at Legal Aid in a rundown building, handling “petty drug crimes, domestic violence, maybe a robbery of a corner store… Not felony murder.”

There are two broken birds here. One is Deshawn, a young Black man Olivia is rather reluctantly representing, charged with a murder he swears he didn’t commit but won’t say who did. The other is Olivia herself, who was thrown into a pit of despair by the crib death of her baby and has wrapped her mourning in a self-protective cocoon.

There are two broken birds here. One is Deshawn, a young Black man Olivia is rather reluctantly representing, charged with a murder he swears he didn’t commit but won’t say who did. The other is Olivia herself, who was thrown into a pit of despair by the crib death of her baby and has wrapped her mourning in a self-protective cocoon.

These two refrains converge in the notion of being seen, as represented by Porter, an itinerant photographer who drifts into their lives with a self-appointed mission to help folks who he thinks need to be seen, and see themselves, for who they truly are.

Taken together, Wilson Noth says in a program note, these are “issues I thought needed to be spoken about” – that is, the cost of code-switching and “society’s preconceived ideas and beliefs about justice and our system’s failures.” They certainly do, and her title palpably signals that intention. But I’m not sure that’s what she actually accomplishes.

The playwright examines the code-switching theme at one remove. Olivia has apparently immersed herself so thoroughly in the white world that she’s lost the ability to toggle. There’s no perceptible shift between her relations with her white husband and her interactions with Black people – in fact she is more formal in speech and bearing with them than she is at home. In the process of assimilating, and swallowing the agony of losing her child, she has lost herself.

Porter sees this, telling her, “I see someone who wants to be told who they are, so they don’t got to ask it of themselves… You’re so darn scared of feeling pain, you just don’t feel nothing at all.”

Porter sees this, telling her, “I see someone who wants to be told who they are, so they don’t got to ask it of themselves… You’re so darn scared of feeling pain, you just don’t feel nothing at all.”

He is, in effect, her savior, her rescuer, the miraculous figure who appears from nowhere to break down the wall she’s built around herself, to lead her into self-discovery and acceptance. If Olivia were white, Porter would be her Magical Negro.

Interestingly, this character who is essentially a metaphor is the one who talks most like a person and not like a script. Wilson Noth writes fluently, but her plotting is mechanical and there’s little subtlety or subtext in the dialogue – characters give each other information, factual or emotional, or purposely withhold it.

That’s Deshawn’s tactic. We believe he didn’t do the murder, and it’s obvious he’s protecting someone. His story is more about perceptions of manhood and obligation than it is about systemic failures that send Black boys and men into the maw of the (in)justice system.

Justin Sturges is compelling as Deshawn, truculent and scared, trying to hide his tender side: he’s an artist and a poet, quoting the Langston Hughes poem almost despite himself. (Olivia’s marveling assessment of him – “This boy is different, he’s talented and soulful” – is an example of the script’s clichés.)

Jahi Kearse is Porter, the photographer/liberator, a rolling stone whose ironic, mischievous demeanor grabs our attention. He’s the most interesting character precisely because he’s enigmatic, and Kearse’s performance is the production’s most convincing.

Olivia’s husband Mark, well-played by Torsten Johnson, is affable, steady, and so devoted to his wife that it’s not only a shock but pretty unbelievable when he defends the tone-deafness of a complacent white friend of the couple who claims she “doesn’t see color,” and soon after easily succumbs to the siren charms of a sexy colleague.

Olivia’s husband Mark, well-played by Torsten Johnson, is affable, steady, and so devoted to his wife that it’s not only a shock but pretty unbelievable when he defends the tone-deafness of a complacent white friend of the couple who claims she “doesn’t see color,” and soon after easily succumbs to the siren charms of a sexy colleague.

The play’s two other characters, in brief appearances, are entirely functional. Deshawn’s mother (Almeria Campbell) provides the back story of his predicament and then disappears from the action. Mark’s beautiful colleague (Rebecca L. Hargrove) exists only to tempt him into an infidelity that’s needed for another turn of the plot.

Olivia is the mainspring of the play, and DeAnna Supplee’s performance is the most disappointing. Where Kearse rejoices in Porter’s playful vernacular, Sturges rides Deshawn’s lines on rage and sorrow, and Johnson is able to make Mark’s sound natural, Supplee struggles to animate her stilted dialogue. (“I want to walk into that courtroom tomorrow, certain that I have acquired all the information I possibly could to do the very best job I can.”) The wrenching monologue in which she finally connects with her grief and breaks through that wall, however, is truly moving.

Kimille Howard’s production is crisply staged, its drama well paced, and her cast show a strong commitment to the material. I was puzzled by her choice to set it, apparently, in the pre-digital years of the 20th century – a 35mm reflex camera in Porter’s hands, LPs in Olivia’s and Mark’s apartment – despite the script’s specifying “Present Day” and the playwright’s clarity that its issues are very much of the present.

The settings are nicely suggested by David Murakami’s projections on the bare walls of the stage: the skyline view from Olivia and Mark’s penthouse apartment; the grungy hallway outside the Legal Aid office; the impassive faces of the jury at Deshawn’s trial.

Wilson Noth notes that most of the show’s creative team, not just the cast, are people of color – a powerful gesture and a significant practical step in an industry that is still overwhelmingly white. The same goes for BTG’s decision to develop and stage this play. I just wish it lived up to its ambitions.

Photos by Jacey Rae Russell

In the Valley Advocate’s present bi-monthly publication schedule, Stagestruck will continue to be a regular feature, with additional posts online. Write me at Stagestruck@crocker.com if you’d like to receive notices when new pieces appear.

Note: The weekly Pioneer Valley Theatre News has comprehensive listings of what’s on and coming up in the Valley and beyond. You can check it out and subscribe (free) here: http://www.pioneervalleytheatre.com/

The Stagestruck archive is at valleyadvocate.com/author/chris-rohmann

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email Stagestruck@crocker.com