It’s become standard practice in the region’s theaters to offer a land acknowledgement before every performance. As Jacob’s Pillow’s artistic director Pamela Tatge says every night, “The land on which we dance is the ancestral homeland” of the Native peoples whose footsteps trod this ground for centuries past, and still do. “We pay honor and respect to their ancestors, past, present and future.”

I found that tribute particularly appropriate to both performances I attended at the Pillow last week. The mainstage show was performed by a New Zealand-based company, Black Grace, whose members dance on the ancestral lands of the Māori people, called Aotearoa in their language. And the early-evening show was danced more literally on the land, the festival’s outdoor platform stage against the backdrop of primeval forest and valley, .

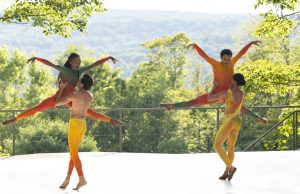

On that stage was Dichotomous Being, an evening of departure and expansion for Taylor Stanley, a principal dancer with the New York City Ballet. It began with a solo from George Balanchine’s 1957 Square Dance, establishing Stanley’s balletic chops before moving into a suite of new works and adaptations – opportunities, in the words of a program note, “to break away from the rigidity and performative prescriptions” of ballet – including world premieres by innovative choreographers Jodi Melnick and Shamel Pitts and featuring a supporting cast of graceful black, brown and white performers.

On that stage was Dichotomous Being, an evening of departure and expansion for Taylor Stanley, a principal dancer with the New York City Ballet. It began with a solo from George Balanchine’s 1957 Square Dance, establishing Stanley’s balletic chops before moving into a suite of new works and adaptations – opportunities, in the words of a program note, “to break away from the rigidity and performative prescriptions” of ballet – including world premieres by innovative choreographers Jodi Melnick and Shamel Pitts and featuring a supporting cast of graceful black, brown and white performers.

Mango, performed with three other dancers, was indeed “dichotomous,” a conscious mingling of the old and new. One dancer wore toe shoes, the others were barefoot, for instance, and Stanley’s own gender fluidity was reflected in the partnered moments, carrying the female dancer in balletic lifts, then being lifted by the men.

Two more solos, Mourner’s Bench and Pitt’s Redness, showed Stanley’s astonishing bodily control and expressiveness in undulating, almost slo-mo movements. Melnick’s These Five might well have been made for the surrounding woods. Two branching boughs carried onstage seemed redundant in this setting, where the stage was dappled by leafy shadows cast by the westering sun. James Io’s soundscape incorporated birdsong, thunder and rain before giving way to electronic pings, buzzes and radio static,. as the five dancers enacted a reverent relationship to the earth with languid reclining postures, rising into frenzied movement by the anguished sound.

Two more solos, Mourner’s Bench and Pitt’s Redness, showed Stanley’s astonishing bodily control and expressiveness in undulating, almost slo-mo movements. Melnick’s These Five might well have been made for the surrounding woods. Two branching boughs carried onstage seemed redundant in this setting, where the stage was dappled by leafy shadows cast by the westering sun. James Io’s soundscape incorporated birdsong, thunder and rain before giving way to electronic pings, buzzes and radio static,. as the five dancers enacted a reverent relationship to the earth with languid reclining postures, rising into frenzied movement by the anguished sound.

Neil Ieremia, the founder/director of Black Grace, was raised in a culturally mixed neighborhood in Porirua, a working-class suburb of Wellington. His parents were Pacific Islanders, his neighbors Māori and Pākehā (the Māori word for white people, literally “imaginary beings resembling men”). “One of the richest neighborhoods in New Zealand,” he told the audience, and his multiracial troupe reflected that milieu.

Founded in 1995, the company was originally all-male – as Ted Shawn’s was when he founded Jacob’s Pillow in 1931, which inspired Pamela Tatge’s request that Ieremia revive an early piece for this visit on the Pillow’s 90th anniversary. Minoi is not a dance per se. The six performers never moved out of their V formation, but stomped and slapped their bodies in contrapuntal rhythm to a traditional Samoan song – an antipodean cousin to stepping in Black American dance.

Founded in 1995, the company was originally all-male – as Ted Shawn’s was when he founded Jacob’s Pillow in 1931, which inspired Pamela Tatge’s request that Ieremia revive an early piece for this visit on the Pillow’s 90th anniversary. Minoi is not a dance per se. The six performers never moved out of their V formation, but stomped and slapped their bodies in contrapuntal rhythm to a traditional Samoan song – an antipodean cousin to stepping in Black American dance.

The eclectic program continued with the two-part Fatu, a new work inspired by the art of elder statesman Fatu Akelei Feu’u. Three dancers, garbed in gold, red and white, represented two generations of Māori chiefs and the coming of Christianity. The female dancer, in gold, began with a spiraling solo, to be joined by the men, Red and White, who tussled together, combative but somehow brotherly. They were accompanied by virtuoso percussionist Isitolo Alesana, who then provided the bass voice for a male quartet in a ravishing a cappella version of a song by the Polynesian fusion band Te Vaka.

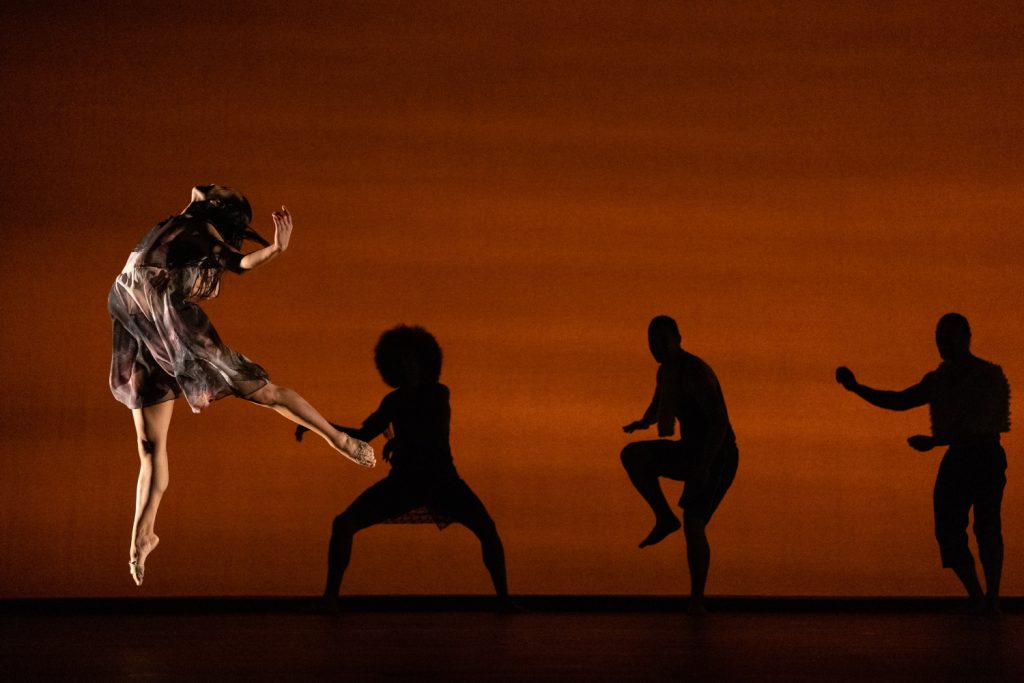

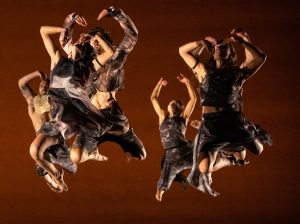

O Le Olaga, or “Life,” was performed to the Gloria in D Major of “the Samoan composer Antonio Vivaldi,” as Ieremia announced with a wink. In a kaleidoscopic whirlwind of kinetic energy, all 14 dancers – including two buoyant elders – found physical polyrhythms within Vivaldi’s polyphony. Shouts of joy punctuated Polynesian chants & floor figures, including an echo of the haka, the greeting ritual posing as a war dance, which New Zealand’s national rugby team, the All Blacks, perform before their international matches.

O Le Olaga, or “Life,” was performed to the Gloria in D Major of “the Samoan composer Antonio Vivaldi,” as Ieremia announced with a wink. In a kaleidoscopic whirlwind of kinetic energy, all 14 dancers – including two buoyant elders – found physical polyrhythms within Vivaldi’s polyphony. Shouts of joy punctuated Polynesian chants & floor figures, including an echo of the haka, the greeting ritual posing as a war dance, which New Zealand’s national rugby team, the All Blacks, perform before their international matches.

That connection is one of the derivations of Black in the troupe’s name, which in NZ is a term of approval for bold, daring action – an apt description of the most exhilarating performance I’ve seen at the Pillow this year.

The last month of the season promises the Pillow’s trademark variety of dance from all corners of the country. These four weeks on the mainstage open and close with ballet – Alonzo King LINES contemporary troupe from San Francisco and the Balanchine-descended Miami City Ballet – sandwiching perennial favorites Hubbard Street Dance Chicago and the Denver-based Cleo Parker Robinson Dance Ensemble, rooted in African-American and worldwide dance forms.

There’s a week-long residency by the adventurous Dance Heginbotham on the outdoor stage, and Liz Lerman and her audacious company perform Wicked Bodies, a dance-theater piece about power and evil designed for the Pillow’s grounds.

Visit jacobspillow.org for full listings and details.

Jacob’s Pillow photos by Danica Paulos & Jamie Kraus

Wicked Bodies photo courtesy of Liz Lerman

In the Valley Advocate’s present bi-monthly publication schedule, Stagestruck will continue to be a regular feature, with additional posts online. Write me at Stagestruck@crocker.com if you’d like to receive notices when new pieces appear.

Note: The weekly Pioneer Valley Theatre News has comprehensive listings of what’s on and coming up in the Valley and beyond. You can check it out and subscribe (free) here.

The Stagestruck archive is at valleyadvocate.com/author/chris-rohmann

If you’d like to be notified of future, email Stagestruck@crocker.com