Britt Ruhe may not be an artist, but she has certainly splashed paint across the canvas of the Pioneer Valley.

For more than three decades, the Granby woman has used her skillset of community organizing, project management and fiscal knowledge to lead nonprofit organizations. But after traveling to Spain six years ago and wandering around the streets of Barcelona looking at public art, she realized those same skills could be used to launch her own nonprofit.

“If I hadn’t been on a solo trip, I would not have come back completely obsessed with street art like I did, because I went on this tour the first day and it was like this whole world opened up to me,” she said.

A native of Amherst, Ruhe was not exposed to street art and murals. When she returned home from Europe, she sought out mural festivals, the first of which was in Worcester.

With a chance Sunday morning free to herself, she decided to drive to the city early only to find that there was next to no one out painting yet. Several of the mural artists had been out painting late the night before and had decided to sleep in.

Strolling around, she finally stumbled on a pair of artists who were working quickly on a mural on the side of a subsidized housing apartment complex. The duo happened to be from Valencia, Spain, and is collectively known as PichiAvo. As Ruhe watched with fascination, she found them to be working as one creative mind and two bodies painting. Little did she know that that chance encounter would lead to her traveling to Worcester two more times to watch the pair work, chat and have coffee together.

“It was amazing to see this complex, beautifully executed piece of art being created before my eyes. And to see how it transformed the space,” she said. “I watched how the neighborhood interacted with it and how excited they were about it and it just shifted everything. And it suddenly occurred to me, I could learn how to do this (facilitate the creation of murals). I have my MBA, and I’ve always worked in nonprofits. I’m good at organizing things. I’m good at fundraising. I can budget. I’m a great project planner. I’m just gonna learn how to do this.”

And she did.

In 2019, she established Common Wealth Murals, a nonprofit dedicated to making the world more beautiful, visually diverse, equitable and inclusive through the creation of public art that is by, for and of the communities who will be most impacted by the art.

That same year, she also launched her very own mural festival, Fresh Paint Springfield. There, thousands of people worked alongside professional muralists from all over the country to help paint 10 large-scale murals in the downtown dining and entertaining district.

The now annual festival takes a series of events, including community painting parties – which brings members of the community together to join in the creation of the large-scale mural – gallery exhibitions, mural tours and a block party.

In total, Ruhe’s nonprofit has facilitated the creation of 45 murals in Springfield with at least 15 more slated for 2023. Of those murals, 25 were created through a community-engaged process. The nonprofit also facilitates private commissions.

“When you put up one mural, they make a difference. But when you put up several murals, in a group … it’s kind of like by a power of 10 effect or a cumulative effect,” she said. “So you get more bang for your buck in terms of the shift in the look and feel of a neighborhood. You can attract more people into the neighborhood to see them. … And there’s economic benefits to that.”

Community Mural Institute

During the first Fresh Paint Springfield, Ruhe experienced another “Barcelona moment” when she met Greta McLain, owner and artistic director of GoodSpace Murals. McLain was one of the artists Ruhe had invited to participate in the festival after seeing her work on Instagram.

Ruhe discovered that McLain utilized an indirect mural-making technique that she’d never seen before.

“She really meaningfully involves the community in both conceptualizing the design and content of the mural,” said Ruhe. “People saw the transformation in the neighborhood and they liked seeing themselves reflected in the work.”

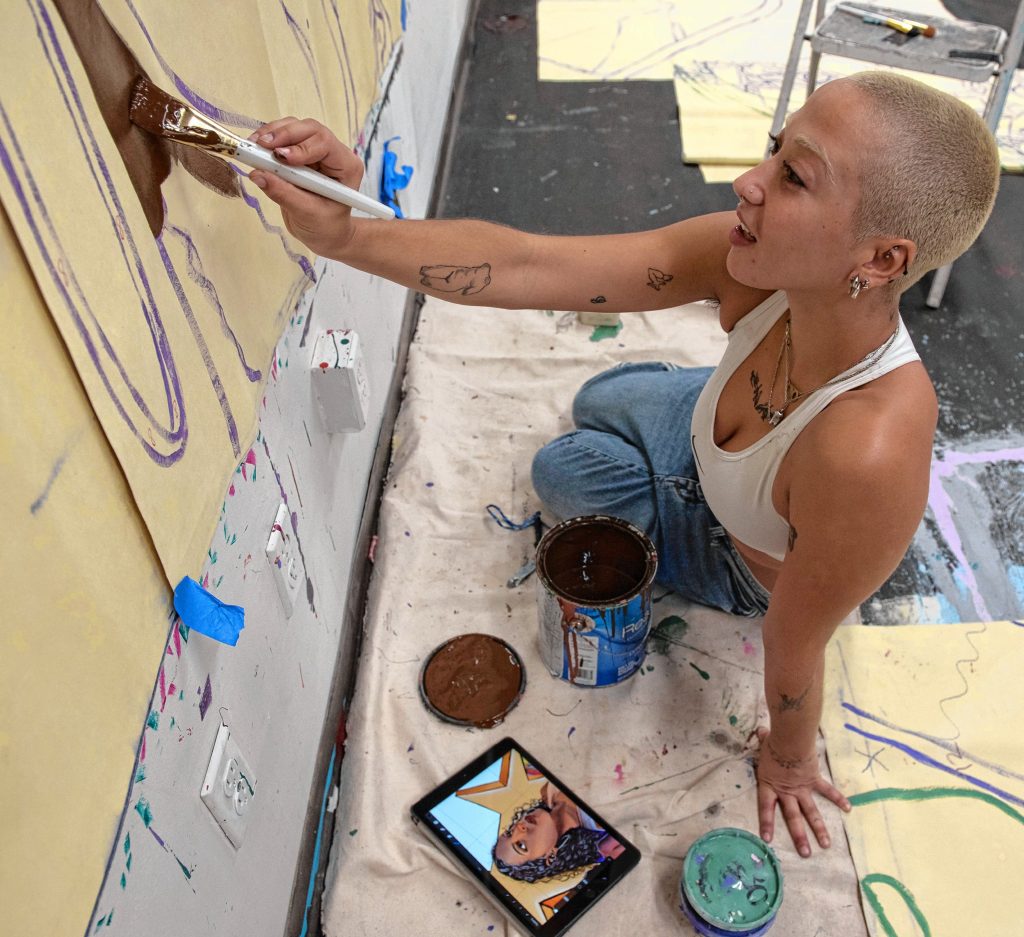

With the innovative technique, called “parachute cloth method,” murals are not painted on the wall, but rather on a non-woven fabric called polytab, also known as parachute cloth. Once a mural is completed, it can be applied to building walls like wallpaper and last longer than murals painted directly on the wall.

The method was pioneered by the city of Philadelphia’s Mural Arts Program, according to McLain, who studied with Joshua Sarantitis, one of the first artists to use this technique.

McLain’s “canvas” was the blank slate of a parking garage wall near Chestnut Towers in Springfield. More than 600 people, including residents of Chestnut Towers and throughout Springfield, helped create the mural.

“Because our commitment is to engage with the community, we actually created the image and then made it a big paint-by-number,” she said. “That engagement made the whole thing magical because it made it that everybody who had participated in one of those paint parties kind of claims their part in the festival – like ‘this festival couldn’t happen without me.’ The magic is how many hands you can get involved.”

To McLain, murals aren’t just a decorative piece, they’re a way to placemake and reclaim space.

In seeing the impact that McLain’s technique produced, Ruhe decided this method was something she wanted Common Wealth Murals to champion and began reaching out to other artists who utilize it.

What she learned, however, was there really isn’t a large pool of people who practice the technique. So together, Ruhe and McLain founded the Community Mural Institute, which combines classroom and online instruction, experiential learning and professional mentorship over the course of nine months.

Through this curriculum, artists and instructors will create and install large outdoor murals that are designed and painted in collaboration with community members. The process begins with facilitated community meetings to help identify themes, images and ideas that mean something to the group. The institute’s lead muralists create designs with support from instructors that will be approved by project organizers, representatives of the community and building owners.

Once the design is approved, mural teams made up of a lead artist and three mural assistants will be trained in the preparation of the parachute cloth method. During that time, each mural design is projected onto the cloth and is traced to create a giant paint-by-number.

From there, the sheets will be brought out into the community for paint parties run by the institute’s team. The team members will then tackle the detail work and overpainting, smoothing out any areas that need it. Mural teams are then trained in the installation of the murals to the buildings.

Since 2019, the institute has taught this method to at least 40 local artists, 60% of whom women and 60% of whom are Black, Indigenous and People of Color. The nonprofit has paid nearly $400,00 directly to artists in this time.

“With this experience, we’re providing people with a road to becoming muralists that they didn’t have before,” said Ruhe.

The impact

In September, Common Wealth Murals worked with Springfield-based queer youth organization Out Now to install a mural on the corner of Gridiron and Main streets on the Stonewall Tavern.

The mural project came to life out of a partnership with Harvard Law School called Students Speak. Through their website, students-speak.org, the entity began asking students around Massachusetts what they need in order to do well in school. As part of that initiative, students are paired up with mentors on how to come up with a one-page testimony to answer that question, according to Holly Richardson, c0-director of Out Now. At the end of that initiative, they asked students what they wanted to do as a form of advocacy.

“Instead of going to the state legislature, we decided to do a mural expressing in a mural story, the answer to that question,” said Richardson.

Out Now ended up working with artist Mimi Ditkoff, a graduate of the Community Mural Institute and a resident of Brooklyn, New York.

As part of the process, Ditkoff created a workshop directed toward the specific kids in Out Now that included activities and games to get to know them, their experiences being queer, and their experiences being queer in school. Through those workshops, she was able to hear the local youths’ perspectives on what makes them confident, safe, heard and seen in the school system, and what makes them feel unsafe, unheard and misrepresented.

The end result was a story of a comparison between the experiences that queer youth have in school now and a radical imagining of what school would look like if it was conducted in a way that was supportive of queer youth, said Ditkoff.

As a queer person herself, Ditkoff felt a deep connection in depicting an image that represented her community. She described the experience as a “transformative” one.

“It helped me feel empowered in my own identity. And it helped me feel seen. And mostly like, it was just so beautiful to see the reaction of the young queer kids I was working with,” she said. “And it was just so incredible to see like, the spaces and hear the comments from the kids that actually live in the city who are queer, who might not feel empowered every day, who might not think they have community to be able to walk down the streets and see themselves represented so largely on the wall. Just to have that and know that brings these kids, some type of representation, some type of empowerment in themselves was just so incredibly beautiful to experience.”

“It speaks volumes. It showed the hard work and dedication that the group put in and it brought the community together,” said Ali S. Haqq, community organizer with Out Now. “The people that participated in the making of that mural are part of history. They now have a place where they can show their families their hard work – it’s creating history. It’s our legacy.”

The reveal of the mural was overwhelming for Tianna Thomas, a community organizer with Out Now. At first, they said they held it all in, but when they got home, they cried. In addition to the story told in the mural, Ditkoff had incorporated a way to remember a member that had passed away in the mural through a butterfly.

They also noted that the outcome of the mural meant a representation that they felt many may not be aware of in the city.

“I think that it shows that we’re heavy in community here and that these murals help create a space for us to be a little bit loud and proud,” said Thomas.

With more and more area artists being trained through the Community Mural Institute and learning how to create murals through the parachute cloth method, Common Wealth Murals will continue to provide more inclusive participation through community-engaged mural design. Ruhe and McLain are hopeful that this approach to brightening of communities will expand throughout the Valley, the state and the country.

“I’ve always believed that art is one of the most powerful tools we have to make the world a better place. It just allows us to engage in other parts of our brain and other parts of our being,” said Ruhe. “When you engage with art, it bypasses all of these barriers that we put up to that allow us to just kind of move through the world without paying attention. And because of that, it can be really powerful to build communities to remember and protect our history, and to seed hopes and dreams for the future. And when we’re doing them in such a quick, large-scale scale and engaging way, it has such a huge impact.”