By STEVE PFARRER

Staff Writer

Time was when Rachel Portesi did much of her photography using Polaroid film. She loved the immediacy of the image, the way each photo was different and often didn’t quite match what her eye had seen, and what she calls “the feeling of Christmas when peeling back the paper to see what I did get.”

But Portesi eventually found her way to a far older style of photography — tintype — that also allowed her to develop images pretty quickly, with each photograph, like a Polaroid, revealing unique characteristics.

Now the Vermont photographer has combined a technique first developed in the 1860s with a subject all her own: “Hair Portraits,” a series of sepia-toned portraits of women in which she has sculpted her models’ hair into elaborate designs that seem to defy gravity, and which speak to a tangled history of how women have been portrayed, especially by men.

Portesi brings that work to the Valley beginning this weekend in a new exhibit, “Rachel Portesi: Looking Glass,” that opens Jan. 15 at the von Auersperg Gallery at Deerfield Academy.

The show, which runs through March 1, features a mix of larger tintype portraits, a selection of 8 by 10-inch Polaroids, 3D viewmaster images, and video installations that showcase elements of the process Portesi used to create her tintype portraits.

In a recent phone call from her studio in Saxtons River, a village about 20 miles north of Brattleboro, Portesi said she’s thrilled to bring her work to the von Auersperg Gallery — in recent years she’s exhibited works from “Hair Portraits” in Vermont, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts — because the Deerfield exhibit will provide the most wall space she’s had to work with.

“It’s a great opportunity to show the range of work in this project,” she said.

Her interest in tintype, in which an aluminum plate is treated with a liquid silver solution that reacts to the image framed by a camera’s lens, began in 2014. Portesi said she’d spent much of the previous seven years raising her young son and was, in a way, searching for a new identity and a new photographic direction.

“I’d been a photographer, then I’d pretty exclusively been a mother for several years,” said Portesi, 51. “In 2014 I got back to being myself, or having some time to myself, but I wasn’t really the same person … I had this sense of starting anew.”

That same year, she took a course in tintype photography. One of the big appeals was that it also quickly produced images, though the process also requires long exposures — about 30 seconds — during which the person being photographed cannot move.

Tintype photography was largely replaced by other methods by the early 20th century, Portesi notes, but it’s enjoyed renewed interest in more recent years, as have other older photographic techniques, as a response to the ubiquitousness today of digital photo images.

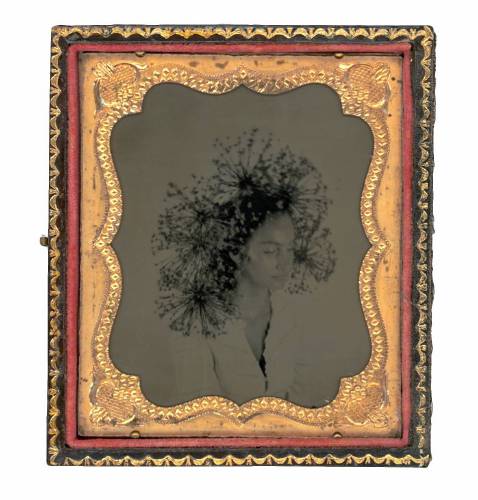

“Willa Star of Persia,” tintype photo in antique frame by Rachel Portesi Photo courtesy Rachel Portesi

It took her awhile to find the right equipment (and funding) to begin taking tintype photos, but Portesi now works with a huge box camera with accordion sides, mounted on a stand, as well as a big blanket that she throws over her head to take her pictures — like someone shooting family portraits at a 19th-century fairground.

Put up your hair

Her interest in photographing women’s hair in unusual ways grew out of a number of threads. Portesi says she was reflecting both on her own life and getting older, as well as on the idea of women’s hair — especially longer hair — as a symbol of fertility and sexuality.

Yet those images of fertility and sexuality have largely been presented through “the male gaze,” as Portesi puts it, at the same time that long hair on women has sometimes been portrayed as a sign of madness, such as for Ophelia, a key character from Shakespeare’s “Hamlet.”

“I was interested in the idea of women taking control of their hair, empowering themselves to present their hair in different ways,” she said.

Some portraits are also homages to some of her favorite artists, such as Frida Kahlo.

“Different” is certainly one way to describe Portesi’s work. Her photos are really visual records of sculptures, in which women who model for her have their hair twisted, furled, and stretched into myriad patterns, some of which are held aloft with pins or fishing line. Their hair is sometimes interwoven with flowers, leaves and branches to create fantastical settings.

In “Frida,” for instance, model Isabel Rodriguez, her head turned to the left with her eyes closed, is adorned with leaf-covered branches that extend to the left and right past her head and across part of her chest; her hair, pulled into a large bun, can only partly be seen.

In “Goddess,” Rodriguez is engulfed in a sort of cloak of enormous dark leafs and crowned with a smaller collection of light-colored flora; only the model’s face and neckline are visible.

Preparing these elaborate tableaus typically takes at least two hours, Portesi says, in which a model sits and the photographer arranges her hair, in some cases pinning it to scaffolding she’s erected on a wall, or connecting it to fishing line (Portesi is an angler) hung from her studio ceiling.

Photographer Rachel Portesi works in her studio with her tintype camera, a photo technique also known as wet plate collodion. Photo by Madelin Lyyli Aho

“It’s a pretty involved process,” she said. “Just preparing each (photographic) plate takes a half hour by itself. I usually get one good shot a day — I feel really fortunate if I can get two.”

But that whole process is made easier because Portesi works with a small number of young models, two in particular, who she’s known for years and considers family. Some are also students of hers and have an important role helping design the staging for the photos.

“I’m really close to them, and I think that creates a kind of intimacy that adds to the overall tone of the photos,” she said.

That sense of intimacy is enhanced in the Deerfield exhibit by the inclusion of numerous smaller photos and diptychs and triptychs, many of which are displayed in antique frames.

Another work, “Chandelier Hair Polaroid,” features 16 small shots of a model with twisting, Medusa-like columns of hair rising above her head; almost all the images are shot from behind, though in one the woman has turned partly to the camera, an enigmatic expression on her face.

Portesi says she’s not wedded to antique photography techniques — “I’m not a purist,” she said with a laugh — and she’s used digital photography, shot formal portraits for private clients, and in general is open to a range of approaches and subjects. Of late she’s been photographing various scenes from nature.

But “Hair Portraits” remains her key interest right now. “I see this as an ongoing exploration of womanhood and these different periods of our lives, including my own,” she said.

More information on Rachel Portesi is available at rachelportesiphotography.com.