By ROBIN GOLDSTEIN

For the Advocate

Since the birth of the progressive era, western Massachusetts has been a hotbed of progressive activism. But some of that activist history might surprise you.

Progressivism was a Protestant social reform movement that swept America starting in the late 1800s. From the start, a central element of the Progressive philosophy was the idea that government should pass and enforce all sorts of laws against immoral practices by individuals and companies. Initially, these immoral practices included child labor, discrimination against women, and many different forms of “deviant” private behavior.

The early Progressives’ definition of “deviance” was built around Protestant ideals of “Temperance.” One of their main policy goals, for instance, was the total illegalization and criminalization of alcoholic beverages, which was eventually achieved through Prohibition. Other progressive goals included the criminalization of tobacco, sex work, homosexuality, and oral sex (which was added to the definition of “sodomy” in the early 1900s). Progressives also supported eugenics and the compulsory sterilization of people who were “unfit” to reproduce.

And then there was cannabis. On April 29, 1911, Massachusetts, by this point a major Progressive hub, became the first in the nation to prohibit weed with its “Act relative to the issuance of search warrants for hypnotic drugs and the arrest of those present.” In the bill, state lawmakers, taking political advantage of public sentiment against Sikh and Punjabi immigrants — whose non-Christian habits white Progressives viewed as deviant — called the plant “Indian hemp.”

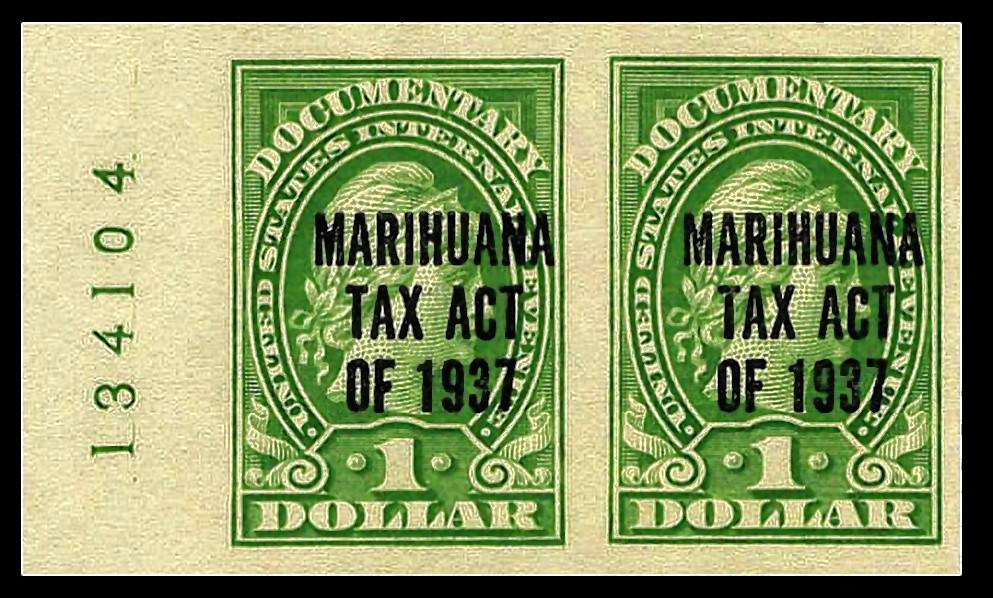

WIKIPEDIA

In 1911, Massachusetts, a major Progressive hub, became the first in the nation to prohibit weed. California and other Progressive-leaning states soon followed suit with weed prohibitions of their own. A couple decades later, so did the U.S. federal government, with the 1937 Marihuana Tax Act.

California and other progressive-leaning states soon followed suit with weed prohibitions of their own. A couple decades later, so did the U.S. federal government, with the 1937 Marihuana Tax Act. During the Mexican revolutionary wars of 1910 to 1920, immigration to the U.S. from Mexico spiked, and anti-immigrant sentiment shifted its focus from South Asians to Mexicans. So the FDR administration strategically chose the word “marijuana” in the language of its national prohibition.

Over the next three decades, progressive activism in America slowly drifted away from its Protestant roots. In the 1960s a new generation of hippies emerged as vocal activists for social change. Few hippies were Christian, and many rejected the social, moral and political principles of their parents’ generation. Although Progressivism was still associated with left-leaning social justice and government intervention to achieve social reforms, many activists no longer identified as “progressives,” and even fewer identified with the original moral principles of progressivism, especially when it came to sex and drugs.

My parents met in the mid-’60s, while they were both students at Northeastern. Like many of their hippie friends, they met and bonded over their opposition to the Vietnam War. When I asked my dad about his first encounters with weed, he immediately started talking about the anti-Vietnam-war movement. Anti-war activism and the ideals behind it were the foundations of their social life, and smoking weed — maybe in part because it was illegal — became a key symbol of rebellion against the government they so hated.

Neither of my parents had ever heard of weed in high school, but both of them were surrounded by it from their first days in college, especially at anti-war protests. Almost everyone in their group of anti-war friends was smoking weed and experimenting with psychedelics. Smoking weed and protesting Vietnam were inseparable.

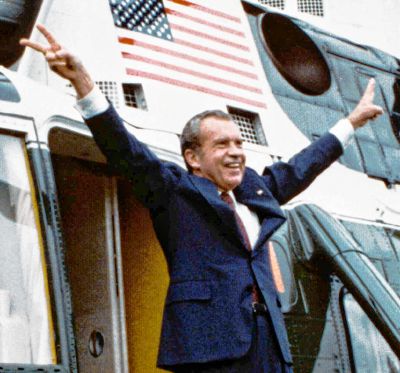

Enter Richard M. Nixon and his 1970 drug law, the Controlled Substances Act, which launched the modern War on Drugs.

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

We have President Richard Nixon, in office when the Valley Advocate began in 1973, to thank for the 1970 Controlled Substances Act, which launched the modern War on Drugs.

Tricky Dick’s main purpose was to imprison some of his most vocal political opponents: hippies and Black people. “We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or (B)lack,” Nixon’s chief of staff John Ehrlichmann later admitted, “but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and (B)lacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities.”

By the time the Valley Advocate was founded in 1973, the Vietnam War was two years away from finally ending. At the same time, a new one was ramping up fast: the War on Drugs. Before long, Nixon was using U.S. trade policy to bully other countries into criminalizing weed and psychedelics as severely as we had. And on this issue, the first-generation Progressives would have been on his side.

The next two decades would see millions of Americans taken away from their families, mostly poor, mostly minorities, generations of boys and girls raised without fathers, and a groundbreaking expansion of the American prison system, including a huge boom in for-profit prisons. Mandatory minimum sentences were introduced, even for nonviolent drug “offenders,” taking discretion away from judges even when they had the utmost empathy for their victims. Most of the “offenses” were just for weed. The War on Drugs, which rages on today, would eventually harm more Americans than any war on our soil since the Civil War.

It was not until the 1990s, after a brutal span of drug imprisonments in the 1980s, that a few individual states began dialing back on weed prohibition, starting with the legalization of medical weed in California in 1996.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Justice — even under President Clinton, who had admitted to smoking weed (or at least trying to) — continued to enforce the federal prohibition aggressively. Until around 2013, feds would even bust mom-and-pop medical caregivers that were 100% compliant with state laws, prosecute them like drug kingpins, and send them away to federal prison for life. It is only in the past couple of years that discussion of lifting the federal prohibition has been discussed seriously, and still nobody knows how long it will take.

It’s hard to say when the comeback of the word “progressive” really began, but it’s in full swing now. People started using it a lot more in the 1980s and 1990s, often interchangeably with “liberal” or “liberal Democrat.” By 2018, “progressive” was an even more fashionable term than “liberal.”

When I first started studying and learning about the history of progressivism, I was first deeply confused by its sex-negative, weed-negative roots. But the first Oxford English Dictionary definition of “progressive” is simply “happening or developing gradually or in stages; proceeding step by step.” Generational changes in religious beliefs and their accompanying moral structures are an old story in America. “Step by step” doesn’t necessarily mean maintaining a single straightforward direction. You can wander, moonwalk, do-si-do.

In the latest generation of progressives — today’s young people, four or five or six generations below the founders of the Progressive movement — the prevailing definitions of moral deviance have undergone yet another major shift. The 1960s and 1970s ideals of U.S. military non-intervention, for instance, appear to have faded, and many (though certainly not all) people who now identify as Progressives now support our involvement in foreign wars.

These days you’re less likely to hear progressives talking about the immorality of dropping bombs than about the immorality of hate speech, gas guzzling, gun ownership, non-vaccination, or — in perhaps the most radical departure from their forefathers — sexual intolerance.

One thing that hasn’t changed for a century, though, is the progressive view on tobacco use, which many present-day progressives still view as deeply immoral.

When it comes to weed, it’s a different story. In Massachusetts or California, you’ll get dirtier looks for smoking a cigarette on the street than for smoking a joint.

Progress?

I guess.

I find it particularly ironic that latter-day progressives in Massachusetts, California, and other blue states were among the first to push for legalization, given that their Progressive forefathers were also the first to criminalize weed.

A parallel irony is that the United States has now taken the lead in re-de-criminalizing weed, while most of the other countries that Nixon initially strong-armed into joining our War on Drugs still lag far behind in their own progress. Many more victims of Richard Nixon’s ghost now live outside our shores than between them. Malaysia still has the death penalty for the possession of an amount of weed that would be legal in Massachusetts.

Here’s hoping that 50 years hence, when the Advocate turns 100, our great-grandchildren will look back on the War on Drugs, everywhere in the world, as a distant memory. But let it not be a memory so distant that next century’s generations of progressives, whatever ideals they eventually adopt, will ever have to learn its gruesome lessons again.

Robin Goldstein is a research economist and director of the Cannabis Economics Group at the University of California, Davis. He is also a 1% shareholder of Cambium Analytica, a cannabis testing lab.