By BOB FLAHERTY

For the Advocate

If it was just that hippie rag, as detractors liked to rank it, well we hippie ragamuffins devoured it front to back. It spoke our language, the F-laden part included, and it was as underground as the music we toked to.

But we soon realized, as the paper’s circulation rapidly doubled and tripled, that there were more of us than we thought. The Valley Advocate, reflective of our attitudes on music, nukes, race, global warming and Nixon, Nixon, Nixon, had an audience. Our paper had arrived.

The Orifice

They were copy editors, Geoff Robinson and Ed Matys, both in their early 20s, putting out the Hartford Courant five nights a week, grousing over what a conventional daily paper covers and what it does not.

“Classic example,” said Linda Matys O’Connell, who was married to Ed Matys at the time. “Ed calls me. The paper sent a reporter to cover the anti-nuke protests at the Millstone plant. But the edited story ended up with no quotes from the protesters, only officials and a spokesman for an opposing group. That was it right there.”

“We had no idea that the Boston Phoenix or the Village Voice existed,” said Geoff Robinson. “Then my sister at Cal Berkeley sent me a copy of the San Francisco Bay Guardian — ‘Did you ever see anything like this?’ — I was blown away, so was Ed. Over that winter of ’72-’73 we just decided to give it a go and break out of the daily.” Robinson, and Ed and Linda Matys each kicked in $1,500. “The odds were that it’d go belly up and we’d figure what to do next.”

They found digs in Amherst. “320 North Pleasant, in the basement of good old Bob Brown’s insurance agency,” said Robinson. “By basement, we mean basement, no windows, no air, desks all squeezed together. And it’s not like we hopped onto the computer and started typing — we were still working with hot lead and setting lines of type.”

That late spring and summer found the pair scouring for equipment and advertisers while Linda held down a job at UMass to keep things afloat. “Soon as I got out of work I was down in the basement, the Orifice, as we called it, all the time writing stories,” said Matys O’Connell.

“I love it!” cried the late Steve Vogel, owner of Faces of the Earth, the iconic shop of quirkiness once tucked away in the center of Amherst, behind Ren’s Mobil. “I’m on board!”

“After that it just came flowing into us,” said Robinson. “We’re thinking, sell this many ads, we can hire, expand and pay the phone bill.”

Naming the thing took some time. “We came from traditional newspaper backgrounds,” said Robinson, “we knew all the daily names, the Journal, the Courier. We wanted it to have meaning — to go out there and state a case and try to advance a principle. We were fighting for gay rights and advocating for transparency.”

The “Valley” part, on the other hand, came as a sign. “No one we knew referred to this place as the Valley,” said Robinson. “Then we saw this road sign, Route 2, I think: Entering the Pioneer Valley. We had no idea. Nobody had heard of it. That’s going to tie the whole thing together with all three counties!”

The next brainstorm concerned arts and entertainment listings. “We saw it as a good way to anchor the paper,” said Robinson. “There was a vacancy, especially with live music. There was no such thing as a calendar — you had posters on light posts.”

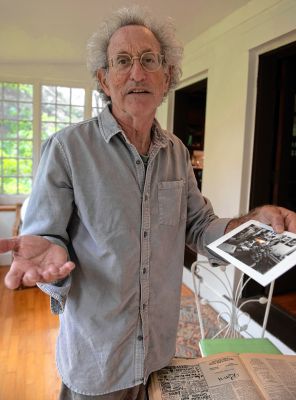

STAFF PHOTO/CAROL LOLLIS

Valley Advocate co-founder, Geoffrey Robinson, talks at his home in Montague about the early days of the paper. The first office was in Amherst: “320 North Pleasant, in the basement of good old Bob Brown’s insurance agency,” said Robinson. “By basement, we mean basement, no windows, no air, desks all squeezed together. And it’s not like we hopped onto the computer and started typing — we were still working with hot lead and setting lines of type.”

The paper would hit newsstands on Thursdays, giving readers ample time to choose a good night out. Open to the “Beer n’ Boogie” pages in ’73 and you’d be flipping heads or tails: NRBQ at the Rusty Nail, Ed Vadas at the Zodiac Lounge, Fat at the Hideway, Clean Living at the Crazy Horse Club, Randy Newnan, Chick Corea and Donovan, yes, Donovan at the Sanderson Theatre.

And for the whole family: “Room of Chains” and “Teenage Tramp” at the Red Rock Drive-In.

Robinson’s brother, a calligrapher, designed the logo, and out went the Valley Advocate, “The Alternative in the Pioneer Valley,” September 19, 1973 — to college campuses and selected retail outlets, not to mention a bundle of 50 for Faces of the Earth. People soon figured out where you could grab the Advocate.

Sam Lovejoy

To have the original 1973 issue in your hand is to be astounded by the size of it, like Moses with the Ten Commandments, coupled with the itty-bitty type required to fit a ton of fully reported long-form copy into its 24 pages. No wonder we all need glasses now.

Its cover story on Michael Metelica and the demise of the Brotherhood of the Spirit commune in Leyden has the legendary self-promoter decreeing that all commune members find employment. Half of them fled. When the Brotherhood and all its holdings were attempting to ease its way into Turners Falls, the resistance from town officials — who may or may not have read “Helter Skelter” — was rife with roadblocks.

But later, when Northeast Utilities targeted Montague as an ideal location for a nuclear power plant, most of the town’s then 900 residents, according to Dorothea Katzenstein’s article, thought it was great — the tax base alone! “There’s nothing to worry about,” said one elected official, quelling any concern over accidents and radiation releases. “They wouldn’t build ‘em if they weren’t safe.”

STAFF PHOTO/CAROL LOLLIS

The cover of the first issue of the Valley Advocate, “The Alternative in the Pioneer Valley,” September 19, 1973.

Then the power company erected a 550-foot weather tower to test wind direction if there were such a leak, which compelled Sam Lovejoy of the Montague Farm Commune to fell the thing with a crowbar and turn himself in to police.

The Advocate gave the trial full coverage: “Jury selection took a day and a half. At least a quarter of the people interviewed worked for the power company, had relatives who worked for it, or owned stock in it.”

Advocate reporters did not shy away from editorializing in news stories, a thing discouraged in conventional dailies. Wrote Don St. Pierre: “At one time (Montague) was a busting mill town complete with canals, child labor and a bar at every corner … what’s left is a group of people ready to take the first thing that’s offered.”

Other voices, like the Union of Concerned Scientists, sited waste disposal and expensive breakdowns associated with the plants, and people leaned in and paid attention (environmentalists were only just beginning to gain credibility in 1974).

From Harvey Wasserman’s coverage: “If Lovejoy is found innocent (he was) it must be interpreted as a loosening of the legal boundaries on civil disobedience in general and on nuclear power plants in particular.”

“We had a No Nukes movement before you knew it,” said Robinson, “emanating from here.”

Those in power began to take the Advocate seriously. One headline sticks in Robinson’s mind 40 years later: “‘45 Minutes to Kill.’ Springfield cops had a man in custody and took 45 minutes to get him to a hospital where he died. Talk about shock waves. I can’t say that’s when things changed in the Springfield PD, but it got traction on the issue.”

In the paper’s two-bit Ads department, meanwhile: “No Nukes bumper stickers — Box 30, Montague.”

The first year

‘These were not even issues on anyone’s horizon,” said Robinson, paging through a bound copy of year one. “Women’s rights are taken for granted now but we were putting that in front of people — rent discrimination, child care, shelters.”

In a ’73 story about a shakeup in area rental practices, especially the discrimination of single women, one landlord wondered: “Why aren’t they home with their parents?” Another, thinking of women as helpless, rented only to married couples for upkeep purposes — “Who’s gonna shovel and mow?”

Like many of the Advocate scribes initially hired, journalism was a learn-as-you-go proposition, peppered with a 1960s skepticism. “I didn’t even know what a byline was,” laughed Chip Ainsworth, who had a sports and general assignment beat for years. “The brainstorming sessions were amazing — we’re pitching stories no one would touch. There was this real sense of fun.”

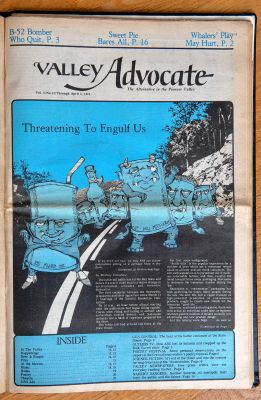

STAFF PHOTO/CAROL LOLLIS

A 1974 Valley Advocate cover. Reflecting on his 20 years at the paper, 18 as music editor and production supervisor, David Sokol said, “We were all the same age, the newsroom was funky but professional, lots of music, lots of marijuana smoking — people going out to the parking lot and I’ve got five papers to put out. But we were so tightknit, people pulled together, and there was always music.”

Though not to be confused with a get-rich-quick scheme.

“Pay not great, with no benefits,” said Ainsworth. “I overheard Ed Matys interviewing someone for a reporting job: ‘If you want to work for an alternative newspaper you have to be willing to accept alternative salary.’”

But as sportswriter, Ainsworth often got to cover his beloved Red Sox, sitting in the dugout of his dreams. It was in the visiting Yankees locker room, though, after a Sox win, where he got a quote from Sir Reginald Jackson as reporters gathered around his locker that Ainsworth was sure the paper wouldn’t print. “And they printed it! Even the headline was great — ‘The Boys of Zimmer’” (Don Zimmer was the Boston manager).

Ainsworth started out selling ads but had the wrong temperament. One prospective client opened up the first issue and perused it page to page. “He says, ‘I’m not impressed.’ And I’m nodding like I’m agreeing. We were told at every turn that the paper will never survive, that enthusiasm only got you so far. But Geoff and Mitch (Young) were pretty sharp cookies. Then Bob Diamond came along, another natural who’d talk the bark off a tree, and we continued to grow.”

Linda Matys O’Connell took over as editor pretty early on as Robinson and Ed Matys took on publisher roles. “We needed to expand and I was happy to do it,” she said. The Springfield Advocate came to be in the mid-70s and New Mass Media was born, Robinson’s then partner Christine Austin playing a major role. Advocates in Hartford, New Haven and Fairfield County soon followed, each with its own staff.

“We did get onto it,” said Robinson. “We tackled major issues, from Vermont Yankee and ground zero to police brutality in Springfield. At the New Haven Advocate it was gloves off with the police department and the FBI, hard-nosed journalism. Nobody else was doing it.”

“And what a magnet it was,” said Matys O’Connell. “We were surrounded by smart and persistent and creative folks. You’d learn about people in the job interview. What were their values? Why would you want to do this? We weren’t looking for Journalism 101; we wanted people who were not prepared to lie down to authority. And a sense of humor — the amount of laughter taking place down in the old Orifice was something else.”

The operation moved to Amity Street in Northampton soon after, and to the fresh air of Hatfield a few years later.

Half century

Compared to Northamptonites recently pondering the 100-year-old presidency of former mayor Calvin Coolidge and all the telegrams, silent films and segregated baseball teams that marked the era, 50 years seems like nothing.

Except there were phone booths, not smartphones, cigarettes in the workplace, and no one had yet heard of “politically correct.”

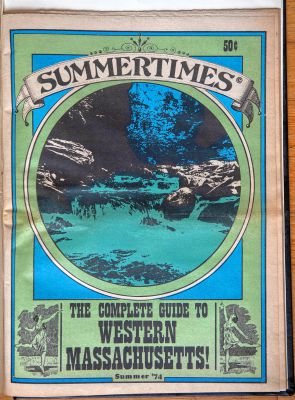

STAFF PHOTO/CAROL LOLLIS

A 1974 Valley Advocate cover. According to co-founder Geoff Robinson, naming the paper took some time. “We came from traditional newspaper backgrounds,” said Robinson, “we knew all the daily names, the Journal, the Courier. We wanted it to have meaning — to go out there and state a case and try to advance a principle. We were fighting for gay rights and advocating for transparency.”

With the success of the all-woman rock band Fanny, Eric Benjamin’s far-reaching interview with Bonnie Raitt, who’s only female role models growing up were folksingers, had the young singer’s prediction: “In the next five years they’re going to be a bunch of girls busting their asses in order to learn how to play a Strat like June Millington.”

On her opening for Jackson Browne, Taj Mahal, James Taylor and others, Raitt said, “It’s kind of nice to have a girl open — it’s so different.” (OK, now it seems like a century ago.) Raitt, now 73, with a net worth of $12 million, expressed the hope in ’73 that with all her gigging she’d soon be able to add another guitarist to the act.

Note: A Zero Mostel double-bill at Amherst College: “The Producers” and “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum.”At Bartlett Auditorium: “A Moon for the Misbegotten.” Heads, tails.

The more things change …

Ainsworth’s 1973 story on stores cracking down on shoplifting quotes one merchant: “Twenty years ago it was just petty stuff; now you’ll catch kids trying to walk out with five pairs of ski gloves or their pockets loaded with socks.” One young woman, confronted upon emerging empty-handed from a dressing room with clothing bulging under her sweater said: “Those are my tits.”

Fast forward to 2023 and organized goon-squads who storm into stores with hammers and run out with half the stock. Kids these days.

J.M Bartman’s “Bargains in the Bin” told how the creative record-buyer could flip through the cut-out bins and find discontinued albums for $1.98, to counteract the outrageous prices shelled out for new releases like $5.98. This is decades before mp3s and royalty free downloads and the myriad ways we savvy consumers of today get to rip off recording artists altogether.

In “Quick Tales,” in ’73, Oregon becomes the first state to decriminalize possession of weed, sort of. They still didn’t allow you to grow it or sell it. You could buy it, as long as you didn’t buy it from someone selling it. Catch 22 was a popular game to play whilst smoking bones in Eugene, obviously.

STAFF PHOTO/CAROL LOLLIS

A Valley Advocate cover from 1973, the first year of publication. The paper was founded by Geoffrey Robinson and Edward Matys. Robinson’s brother, a calligrapher, designed the logo.

And of course, Richard Nixon, of whom Howard Ziff wrote in November of ’73: “Suddenly, unexpectedly, for those who hate him, Richard Milhouse [sic] Nixon has become a bore. Like Cagney in the final reel of a 1930s gangster movie attempting a last stand as the ring of lawmen grows tighter, tighter.” (The late Ziff used to host “Hollywood Classics” on Saturday nights at WGBY.)

Equally boring in 2023 is Donald Trump, yes, but can anyone imagine Trump resigning the presidency as Nixon did in ’74 to: “Put the interests of America first?”

In “Conversations with a Bookie,” Advocate readers were given a rare look into the underworld of gambling and how easily one could get fleeced. In 2023, shill play-by-play announcers offer in-game betting opportunities at the touch of a button: “Will Devers hit a homer his next time up?”

In October of ’73 Carolyn Coman wrote about tennis hustler Bobby Riggs, who claimed that women tennis players were “lousy” and then got his ass kicked in straight sets by the immortal Billie Jean King, who was hailed this summer by 19-year-old Coco Gauff upon winning the U.S. Open. It was King who led the fight for equal prize money for women in tennis, and it was the Riggs shellacking that put it over.

If you were a reader, like many, who’d go straight to the funny pages before even glancing at the front page, the Advocate did not disappoint. You had the droll “Sylvia” by Nicole Hollander, the satiric panel “Life in Hell” by Simpsons creator Matt Groening, and the most authentic comic strip since Walt Kelly’s “Pogo,” Alison Bechdel’s “Dykes to Watch Out For.”

The Advocate also was not above hyperbole. A review of a James Montgomery concert likened the mismanaged sound system to “a baby’s cry when burned with napalm.”

A life-affirming force

In ’73, David Sokol had just finished up his senior year at the Daily Collegian, the Advocate was just starting up, and his band, his only source of income, went kablooey. “I needed a real job for sure,” he said. “I reviewed a Paul Simon album for 60 cents a line. I made $3.50, went to Friendly’s and got a big boy cheeseburger.”

Sokol spent 20 years at the Advocate, 18 as music editor and production supervisor. “It was 80% production and 20% music, but that was my passion. We had five papers. Deadlines were grueling and difficult but fascinating — so much talent, the photography of Donn Young alone.”

“What a time. We were all the same age, the newsroom was funky but professional, lots of music, lots of marijuana smoking — people going out to the parking lot and I’ve got five papers to put out. But we were so tightknit, people pulled together, and there was always music.”

Yes, and canines. It was Bring Your Dog to Work Day every day. “There’d be dogfights, y’know, the kind that look real until you see they’re just playing, lots of barking, just footloose and fancy free,” Sokol laughed. “Pam Bricker comes by. The Pam Bricker Band was gonna break and go national. I’m so thrilled to be doing an interview. The whole band is with her, gathered around my desk.”

And then all necks turn to regard a monstrous pile of steaming dog doo, and all Sokol can do is shake his head.

Sokol stands by 99% of the 600-or-so record reviews he wrote for the Advocate. His one regret, the panning of Jackson Browne’s “Late for the Sky.”

“‘Sokol’s a stupid shit!’ was a general reaction,” said Sokol. “They were right.”

But the concert that moves him to this day is the one he would rather have skipped, his assignment to cover Bruce Springsteen in Hartford four nights after John Lennon was assassinated. “I was in shock, we all were. Not excited for the show at all, on this of all weeks.”

Except that Springsteen, then as now (up until his recent illness) transcends.

“Bruce and the E Street Band tear through 33 songs in three and a half hours as if their very lives depend upon it,” wrote Sokol. “The energy, the joy.”

The anthemic cry: “It ain’t no sin to be glad you’re alive” hit like a transfusion. “I left elated. On the fourth night after the killing of John Lennon, an affirmation of life.”

The 80s

Then comes the touchy subject of marijuana in an era when cops would bust you and your head. Editor Kitty Axelson-Berry invited Advocate readers to weigh in (anonymously) on whether 1970s pot smoking would carry over to the 1980s and the grown-up responsibilities inherent.

Wrote one: “I do expose my children to second-hand smoke and I would not believe research that said it was harmful.”

Another: “No pot smoker I ever knew was obsessed; many non-smokers appear quite obsessed.”

And: “As a man, I feel pot opens me up to more positive female traits of compassion, sensitivity and selflessness. Damn, I love my mom more when I’m stoned.”

This was in the midst of D.A.R.E and Just Say No and all the urine tests and clamping down. Flash forward to 2023, where we’re Cheech to each other’s Chong.

Axelson-Berry was another who did not have a rich journalistic background. “But I do have a back-to-the-land degree,” she said, having lived for years in a tent with her husband and daughter in Leverett, then in a geodesic dome, with no electricity or running water. She is lauded for keeping investigative journalism the main meat of the paper. “They were doing wonderful things before my time; we were just riding that wave, doing high quality critical reporting.” As she told one young hire: “No such thing as objective reporting — you gotta have some kind of opinion.”

This is the era of the late Al Giordano, as dogged a reporter as there ever was, an anti-nuke activist in his teens who ran with Abbie Hoffman. His relentless coverage of corruption in Springfield got Giordano tabbed in Rolling Stone as Muckraker of the Year. “Al just had it, you could tell,” said Sokol.

A tragedy that haunts the old guard still is the murder of writer Judith Hart Fournier, stabbed in broad daylight by ex-boyfriend Bob Sawyer, also an Advocate writer, not long after she came out to friends as lesbian. She died that night at the hospital, “the knife still in her,” wrote Giordano. “The legal system proved as impotent as the thin envelope in Sawyer’s passenger seat in containing the knife that ended her life.”

“Judith was a wonderful person,” said Axelson-Berry. “I worked closely with her. Deeply upsetting time for anyone involved. It added to my understanding of trauma, and that good people — that is, people who I knew, or liked, or who were in my group — could do the unthinkable.”

Listings in 1985 had Grandmaster Flash and the Fat Boys in Springfield and New Haven, Lone Justice and the dBs at UMass.

These days Axelson-Berry is an editor at Amherst Indy, the all-volunteer community journalism project that’s ruffled the feathers of a few people involved in the investigation into the mistreatment of transgender students at the Middle School. “The Indy took it upon itself to publish the article that appeared in The Graphic, the student newspaper, and the story really took off,” said Axelson-Berry.

“They say we cause divisiveness in this town, that we’re rabble rousers. Three resign from the school committee and blame Indy and parents for bullying them.”

“That said, I’d love to see more civility in town, more respect for one another, at least try to be nice,” said Axelson-Berry.

The scribe with the longest tenure at the Advocate was Stephanie Kraft, who started in ’74 and retired in 2014.

“She was fantastic!” said Axelson-Berry of her longtime friend. “So smart, so nice, so inquisitive, with great ideas, a terrific researcher, did I mention she was nice?”

“We had adventurous reporters who took chances,” said Stephanie Kraft in a History Bites podcast, “but we had a wonderful audience here, wonderful readers pitching in with interest. Our audience had a lot to do with the Advocate’s survival. In many parts of the country, people were reading less, but in the Valley they did, and still do.”

Boar again? We had that last night

Robinson bought out Ed Matys’ end of the business in 1981 and operated the papers with Christine Austin.

Then came the 90s.

“A lot of people thought they’d seen the heyday of the alternative newspaper,” said Robinson. “We couldn’t sell classifieds like we used to.”

STAFF PHOTO/CAROL LOLLIS

Geoffrey Robinson, Valley Advocate co-founder, says one headline sticks in his mind decades later: “‘45 Minutes to Kill.’ Springfield cops had a man in custody and took 45 minutes to get him to a hospital where he died. Talk about shock waves. I can’t say that’s when things changed in the Springfield PD, but it got traction on the issue.”

There became easier ways for horny humans to hook up. And the internet took care of all that beer and boogie stuff. All those Advocates gradually folded, along with the Phoenix, the Bay Guardian and the Village Voice. Newspapers of New England (Gazette, Recorder) bought the flagship Advocate in 2007.

After selling the papers in 1999 to the Hartford Courant, Geoff Robinson rekindled a romance with a woman he’d known since university days, then an exchange student from New Zealand. “My wife Reihana is 100% Kiwi,” he said. “After the sale it was ‘OK, where are we gonna live?’ Staying in the Valley was attractive because we both love it here, but we decided to take a stab at organic farming in New Zealand.”

They live in the out-outback, a true wilderness, with the nearest neighbors kilometers away. It’s beeswax candles and propane for heat. Robinson has also mastered a way to snare wild boars, tusks and all, and store the meat in the freezer. “It’s traditional … going back to Captain Cook when he left wild pigs here as a planned food source. I wouldn’t call it humane, the snaring, but for those of us who include animal protein in our diet, you have to take responsibility for ending its life. It’s the healthiest food.”

As for journalism, Robinson wrote opinion columns for a daily in Hamilton and the couple has worked together on environmental advocacy stories.

“Our grandkids are there,” said Robinson. “When we come back to the Valley, it’s for all the reasons you know. This area is incredible. There are more Farmers Markets in Franklin County than in all of New Zealand.”

Power and truth

‘I never felt disempowered by my gender,” said Linda Matys O’Connell, the first woman editor of an alternative newspaper. “I learned that I had the capacity to persevere.”

The Matys marriage didn’t work out, but she found her soulmate in Geoff O’Connell, who was hired as editor when she became executive editor. “We kept it professional until it was inevitable,” she said.

The couple left and co-founded the San Antonio Courant, eventually returning to Springfield. They’ve been married 38 years.

Ed Matys is retired and living in Woburn.

The work of photographer Donn Young, now living in North Carolina, comes up a lot when you talk to those who were there. In 1975 police killed an unarmed teen, Rafael Lecodet, in Springfield’s North End, sparking three days of rioting. “I sent Eric Benjamin and Donn Young,” said Matys O’Connell. “The city didn’t want us there, the chief (Paul Fenton) made that clear. Then I got chewed out by a TV news director for quoting witnesses — ‘They have no credibility!’ That made us even more determined.”

“I look through those old papers and I swear we must have been nuts,” said Eric Benjamin. “We all could’ve been killed by Fenton’s goons.”

“Donn Young and the classic art of coverage,” marveled Matys O’Connell. “The power, what he could see. On my wall at home I have a framed picture, the shot Donn took of a bay window, three young boys, maybe five, four and two, the youngest naked, watching the riots in solidarity. The power in telling the truth.”