By STEVE PFARRER

Staff Writer

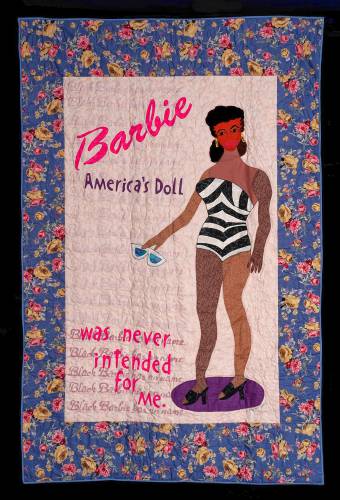

Paintings that date to the early 1800s. Native American crafts and textiles from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Depression-era photographs and ones taken just a few years ago. A quilt that offers interesting commentary on a pop culture topic that was all the rage this past summer.

What do they have in common? All these artworks are part of a new exhibit at Springfield Museums, “As They Saw It: Women Artists Then & Now,” that offers a broad look at how female American artists have approached their subjects and worked to overcome numerous barriers — social, economic, cultural — to shape their stories.

With over 60 works on view, drawn from artists from a broad mix of racial, ethnic and economic backgrounds, “As They Saw It” is a collaboration between curators from the Springfield Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA Boston), and the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, New York.

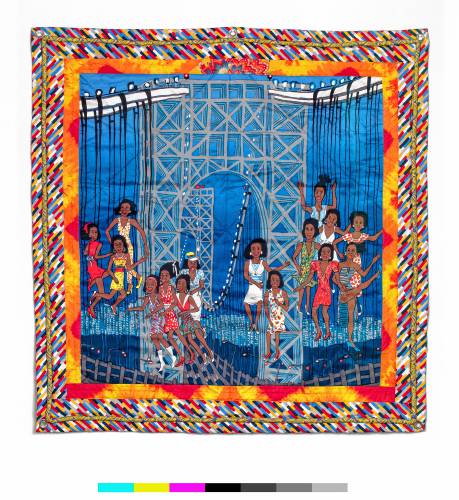

“Dancing on the George Washington Bridge II,” a 2020 quilt by Faith Ringgold, is part of the varied work in “As They Saw It.” Image courtesy Springfield Museums

And the exhibit, whose work is drawn from all three museums, is part of a multi-year initiative at MFA Boston with four regional museums, including the Springfield complex.

The new show might be the only one at which you’ll see an 1815 watercolor by a folk artist, Mary Ann Wilson, who lived openly in upstate New York with another woman, alongside photos by Dorothea Lange — or a quilt by Kyra Hicks, a contemporary African American fabric artist whose 1996 work “Black Barbie” is emblazoned with the words “America’s Doll was never intended for me.”

Or how about a varied display of late 19th/early 20th century baskets by Native Americans from Oregon and northern California, juxtaposed with work by mid/late 20th century abstract painters Alice Trumbull Mason and Emily Mason?

“We didn’t want to limit ourselves to one time period or one kind of genre,” said Maggie North, a co-curator of the exhibit and until recently the lead curator at the Springfield Museums (she’s currently in a doctoral program in art history at Bryn Mawr College in Philadelphia).

“The idea was to have these pieces be in conversation with each other,” North said during a recent phone call from Philadelphia. “I think that encourages us to look at art, to look at the world, in different ways.”

A Diné (Navajo) dress from the late 19th century, cinched with a sash belt made by D.Y. Begay, a contemporary Diné artist. Image courtesy Springfield Museums

A collaborative show — this is the second full one Springfield Museums has done with MFA Boston — is also a good way for museums to “maximize the strength of our collections,” she said.

And, North noted, an important goal of what’s known as the Art Bridges initiative at MFA Boston — a goal shared by Springfield Museums, she added — is to build new exhibits along more inclusive lines, showing work from artists who haven’t received enough past recognition.

“One study we looked at from a few years ago showed that just 14 percent of exhibitions at 25 major American museums were of work by women,” she said. “So this exhibit is one way to address that.”

The show, in the D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts, is divided into three sections. One includes self-portraits and other explorations of identity; a second features work examining themes of “sisterhood” and community among women, such as “Dancing on the George Washington Bridge II.”

This colorful 2020 quilt, by Faith Ringgold, shows over a dozen African American women floating along and just above the framework of the New York City bridge.

A third section looks at multi-generational relationships among women artists, and perhaps the best example is a red Diné (Navajo) dress, dating from approximately 1890, to which a contemporary Diné artist, D.Y. Begay, has added a sash belt.

“That’s the way the dress would have been worn,” said North.

Bucking convention

Though most of the artworks date from the 20th and 21st centuries, some older works stand out for the way they bucked social conventions of 19th century women.

Consider “Self-Portrait,” an 1885 oil painting by Ellen Day Hale, an impressionist painter from Massachusetts who lived and studied in Paris, London and Boston. In the work, Hale looks boldly at the viewer in a way considered unusual and perhaps rather daring for women of that era.

As exhibit notes put it, Hale’s “unabashed gaze” led one critic to declare that the artist displayed “a man’s strength,” which “he meant as a compliment.”

“Maremaid,” a 1815 watercolor by Mary Ann Wilson, a folk artist from New York state. Her piece made the case for female empowerment well before the term was coined. Image couresy Springfield Museums

And Mary Ann Wilson, the New York state folk artist, in 1815 crafted “Maremaid,” a watercolor painting that depicted a mermaid-like figure clutching a weapon in each hand rather than a mirror and a comb. The painting stands out as a “visionary representation of female empowerment,” exhibit notes state.

North says she and her co-curators — all women, by coincidence — from the two other museums were also committed to showing work not just by women but by women of color and Native American women.

“Those artists have historically been even more under-represented,” she noted.

She added that the curating team had been mulling the inclusion of Kyra Hicks’ “Black Barbie” quilt when the much ballyhooed film “Barbie” opened this summer. The resulting media crush about the film, North said with a laugh, “meant that we all said ‘yes’ to including it.”

And in one of the “conversations” North refers to in the exhibit, as well another pop culture reference, next to Hicks’ “Barbie” quilt is a photograph by Cara Romero, titled “Arla Lucia,” which depicts a Native American woman as Wonder Woman.

A member of the Chemehuevi Nation of southern California who also grew up partly around Houston, Texas, Romero did not see herself or her community reflected in popular culture or academia, exhibit notes state — so she opted to fill that void with her own photographs.

“As They Saw It” includes a number of other striking photos. A 1973 image by Nan Goldin, “Ivy in the Boston Garden,” captures a female-presenting person at ease at a time when LGBTQ people had far less visibility or acceptance.

“As They Saw It” at the Springfield Museums features work by American women artists dating back to the early 19th century. Staff photo/Steve Pfarrer

And “Untitled No. 10,” a 1999 portrait by Eve Fowler, shows a determined looking teenage girl wearing wrestling gear, poised to strike — part of a series that Fowler, who’s also a filmmaker and multimedia artist, did on teenage girls playing boys sports.

North says she hopes the exhibit, which runs through Jan. 14 and moves in April to the Fenimore Art Museum, will appeal not just to women but to all manner of visitors — anyone interested in seeing a wide range of art arranged in an unusual context.

“I’d love to see mothers and daughters visit together,” she said. “But really it’s a great opportunity for anyone to consider how art is presented, and how museums can be more responsive to the community and be more equitable.”

Steve Pfarrer can be reached at spfarrer@gazettenet.com.