By DON STEWART

For the Advocate

COURTESY CLARK ART INSTITUTE

Gustave Le Gray’s 1856 image of a “Brig on the Water” wowed viewers at the time, given its uniqueness.

There are those who see winter not as a season but as a siege. They tire of shoveling white glittering fractals from their driveways and see snow as the unnecessary freezing of water.

If you’re among those who don’t consider the frozen monochrome of winter as character building, a welcome escape is yours at Williamstown’s Clark Art Institute. A celebratory exhibit of some 80 original images in paper and photographs displays color, intrigue and sights of many delicate works created more than five centuries ago.

During a press reception, Anne Leonard, curator of the Clark’s prints, drawings and photographs, explained that in the past half century some 4,000 images in paper have been acquired, triple the amount as when the institute began in 1955. “The collection continues to grow. It continues to develop,” she said. “The collection is a living, breathing thing, continuing to change.”

The exhibit ranges from a woodblock by Paul Gauguin and Albrecht Durer engravings to a pastel by Mary Cassatt. Among these treasures are the 19th century’s most well known photograph and a depiction of one of France’s most reviled injustices.

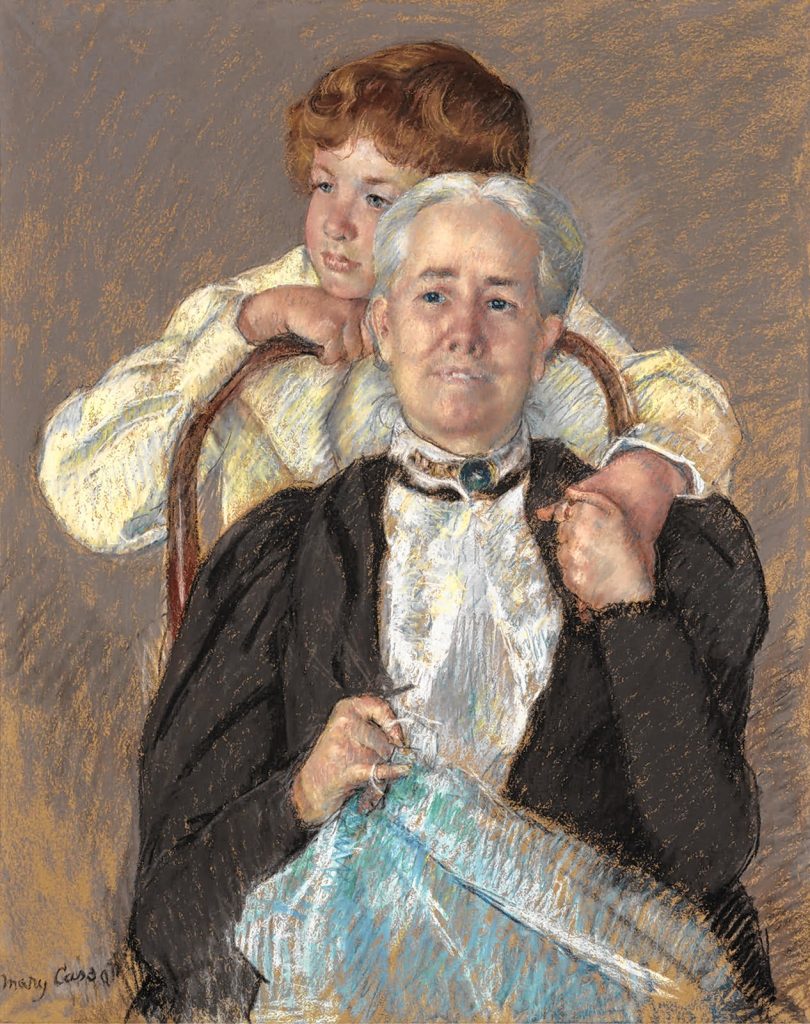

COURTESY CLARK ART INSTITUTE

Hilaire Ledru’s early 19th-century rendering of the final hours of Joseph Lesurques was created with white gouache, crayon and white chalk.

To combat fading, since paper will darken over time, in staging the show there was great care in determining how much candlepower or lumens would light each work. This required a calculation for each image. A lumen is equal to the light cast on one square foot, 12 inches away from a single candle. The illumination for the exhibit, however, is so subtle as not to be noticed.

“It’s incredibly precise,” Leonard said. “We don’t want it so dark here that it feels like a cave and that people are groping around, tripping over benches.” The curator added that “there’s an ironclad rule that (black and white) paper doesn’t get exhibited more than every five years.” Color works are only shown every decade.

Revelation and injustice

Upon entering the exhibit, the largest and one of the more striking images was created in the early 16th century. “The Baggage Train” by Albrecht Altdorfer measures five feet in length and is the seamless construction of several woodcuts.

The German is considered to be the first modern landscape painter, finding subject matter solely in the environment. One of his paintings, “The Battle of Alexander,” is considered to be the first to show the curvature of the earth.

“The Baggage Train” illustrates a parade of suppliers bringing equipment and food stores to the armies of Maximillian I. It’s a masterful rendering of a complex scene complete with camp followers, dogs, a musician and a caravan that stretches out to the horizon.

“It’s a magnificent example of an immensely detailed, realistic and yet beautifully posed design,” Leonard said.

COURTESY CLARK ART INSTITUTE

Mary Cassatt was strongly influenced by Edgar Degas and was the only American woman allowed to join and exhibit with the Impressionists. Here is her 1898 pastel, “Portrait of Mrs. Cyrus J. Lawrence.”

Nearby is another German rendering by Hermann Wohler, a college professor of art. His works were unknown until 1987, some 25 years after his passing, since he created his unique visions in seclusion. His black ink rendering of “The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse” is a nightmarish scene of raging horsemen under stormy skies with shining stars seen above. In the foreground, as a nod to Surrealism, John The Elder is describing the pandemonium for The Book of Revelation.

During the very real pandemonium of the French Revolution, of the 17,000 people estimated to have been executed during that decade, the notorious conviction of Joseph Lesurques had the most resonance. In 1796 he was found guilty of theft and murder. Despite 15 witnesses providing an alibi and scores more attesting to his noble character, he was brought to the guillotine.

“It was a case of a wrongful conviction,” Leonard said. “He only had the misfortune to bear a strong physical resemblance to the perpetrator.”

It’s suggested that the artist Hilaire Ledru was allowed to sketch the wrongfully accused on his last day, given the attention to detail.

Four years later the gang responsible for the crime was captured and executed, yet the French courts never admitted their error. Lesurques’ family was reduced to poverty and his wife went mad. This tragedy spurred the writer Victor Hugo to campaign against the death penalty and a theatrical play made the rounds. France outlawed the death penalty in 1981.

Subtle enough to be missed is a soft graphite rendering of a lion’s head by Rosa Bonheur, the most famous female French artist of the 19th century. Largely self-taught, from an early age she copied the classics at the Louvre and her oil paintings are virtually photographic in detail. She spent hours in abattoirs studying anatomy and for this reason she was among the few Parisian women legally allowed to wear pants. Bonheur wore men’s clothes, smoked tobacco and lived in a castle with a menagerie of animals. A 2022 film, “Rosa Bonheur dame nature,” dramatizes her remarkable life.

Early black and white

Leonard noted that in 1998 the Clark began to collect photographs from the 19th and early 20th centuries. “It was felt particularly with our role as teachers and educators … it was very important to have this in our collection.” The curator added that “it was an aggressive campaign with money put towards a very rapid acquisition of the early years of the medium.”

It’s been said that the most reproduced photograph of the 20th century was taken by Dennis Stock of 1950s actor James Dean walking in Times Square. Almost 100 years earlier, the 19th century image of a ship at sea, taken in 1856 by Gustave Le Gray, became the most popular photograph of its time.

“Brig on the Water” is deceptively simple yet it’s the first time that the details of both the ocean, or landscape, and a pattern of clouds overhead were in the same photograph. With the characteristics of film at the time, it was impossible to correctly expose for both earth and sky on the same glass plate. The Frenchman achieved this by combining two different negatives for the final result.

“It’s not just a mark of his immense skill in the medium, but also this esthetic power,” Leonard said. “It’s a magnificent image.”

COURTESY CLARK ART INSTITUTE

“The Baggage Train” is a masterful, seamless blending of several woodcuts made in 1518 by the artist and Renaissance figure Albrecht Altdorfer.

Gustave Le Gray was a painter, teacher and author, doing much to advance photography as an art while forecasting that “the entire future of photography is on paper.” He was a better lens man than a businessman and, at the age of 40, he ran away from creditors and family, spending his remaining years in Egypt.

The work of Lenox born photographer James Van Der Zee is also exhibited. He spent most of his career photographing the personalities of Harlem and gained international fame for his pictures. Twenty years before his passing in 1983, the Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibited his images. An accomplished musician, for several years he also played in Fletcher Henderson’s band.

Here a 1926 photo “Wedding Day Harlem” displays a handsome bride and groom in finery posed against a painted backdrop. At their feet Van Der Zee has deftly inserted the transparent image of a child holding a doll. The photographer was renowned in creating special effects, often enhancing a picture by drawing on the negative.

Among the photographs shown, from the institute’s collection of more than 1,000, are the works of Berenice Abbott. She was a proponent of “straight photography” with no tricks or gimmicks. Without her, the name of early lens man Eugene Atget, also on display, may not be so widely known. He is remembered for documenting late 19th century and early 20th century Paris, which he knew was quickly vanishing to modern architecture. Abbott successfully campaigned for his work to become more widely appreciated.

She had begun her career working in the studio of the Surrealist Man Ray and went on to create may of the definitive photographs of such luminaries as the poet and filmmaker Jean Cocteau and the author James Joyce.

For those not choosing to travel, the majority of the institute’s collections may be viewed at their website clarkart.edu. Works on paper, print and photography may also be viewed by appointment.

The institute contains one of the most remarkable collections of French Impressionism, English landscape paintings and the 19th century $1.2 million Lawrence Alma-Tadema piano. When acquired, it was the highest price paid for a music box until George Michael purchased musician John Lennon’s Steinway for $2.1 million.

“50 Years and Forward” continues through March 10. Admission is free through March. The Clark is open Tuesday through Sunday, from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. More information is available by visiting clarkart.edu/.