By Melissa Karen Sances

For the Valley Advocate

“And if you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.” — Friedrich Nietzsche

I have never liked ghost stories. But when I heard about Half-Hanged Mary of Hadley, I was spellbound. Not that long ago, and not that far from here, a woman, thought to be a witch, was brutalized and left for dead. But she survived.

For Margaret Atwood, this was a personal horror. Fueled by the possibility that Mary Reeve Webster was her ancestor — her lineage can be traced back to John Webster, the fifth governor of the Colony of Connecticut and Mary’s father-in-law — she began to write. We can thank Mary, maybe, for “The Handmaid’s Tale.” Ultimately, Atwood didn’t know enough about the 17th century to center the novel around Mary’s story. It was instead set in the not-too-distant future, in New England-turned-Gilead, where women are surrogates-at-gunpoint, sexual slaves seen as nothing more than fertile cattle. Unhuman.

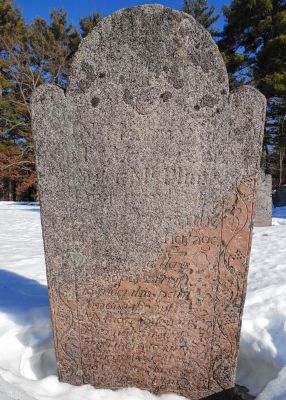

STAFF PHOTO/CAROL LOLLIS

Not that long ago, right here in our Valley, a woman, thought to be a witch, was brutalized and left for dead. But she survived. She is buried in the Old Hadley Cemetery.

In 1985, Atwood dedicated the book to her ancestor, and 10 years later, she wrote a poem from Mary’s point-of-view as she lives through her lynching:

“At the end of my rope / I testify to silence. / Don’t say I’m not grateful. / Most will have only one death. / I will have two.”

I found out about Mary through Jeff Belanger’s Emmy-nominated “New England Legends” podcast, which has chronicled hundreds of haunted happenings since 2017. (A show by the same name runs on PBS). The veteran storyteller, who grew up in Southbridge, is a familiar face and voice at spooky speaking engagements around the world, and his “Half-Hanged Mary of Hadley” episode is a tight-10-minute history lesson, with more than a hint of empathy.

I called the ghosthunter during his busiest month — October — but over two phone interviews, he helped me dig in to the details of Mary’s story, while discussing three other female spirits who linger here.

Belanger is a fast talker who is passionate about the past and what it can reflect back to us. To him, ghost stories aren’t just entertainment; they’re about being engaged with being human. One of most his appealing qualities is that he lays out the facts, and lets you define the truth.

“There’s a moral behind every story and legend that sticks around,” he said. “That’s what haunts us.”

Half-Hanged Mary

In 1659, John Webster, the fifth governor of the Colony of Connecticut, founded Hadley with 60 like-minded, similarly wealthy men, including his two sons, Thomas and William. But within two years, John died of a fever, leaving the brothers destitute, pushed to the edge of town next to the cemetery and the pound. William married Mary Reeve of Springfield in 1670, and soon they became wards of the town. (At this point, William disappears like a ghost from the story, although he died only 10 years before his wife.)

STAFF PHOTO/CAROL LOLLIS

Mary Reeve Webster was buried in an unmarked grave in the Old Hadley Cemetery.

By 1682, Mary, who is believed to have had no children, was in her mid-50s, with an unladylike temper. “She didn’t take any crap from anybody,” says Alan Weinberg, co-president of the Hadley Historical Society and Chair of the Cemetery Committee for the Town of Hadley. “Women were supposed to be meek. She was not a meek person.”

Her greatest sin? She wasn’t grateful to the men who provided for her.

Soon farmers on their cross-town journey were not able to pass her house. Their horses reared at her door, an obvious sign that she had hexed them.

Sylvester Judd, who wrote “History of Hadley” in 1905, described matter-of-factly how the men dealt with Mary’s impudence: “In such cases the teamsters used to go into the house and whip or threaten to whip her, and she would let the team pass.”

But there were other things amiss, and the townspeople collected these stories as evidence of witchery. “She entered a house, and had such influence upon an infant on the bed or in the cradle, that it was raised to the chamber floor and fell back again, three times, and no visible hand touched it,” writes Judd. She also had strange bruises on her body that the town’s women — the wives of the men who beat her — felt entitled to seek out with their hands.

After being charged with witchcraft in Northampton on March 27, 1683, she was sent to Boston to await trial. Despite passionate testimony that she worked in concert with the devil, on Sept. 4, she was acquitted by a jury and sent back to Hadley. Without the means to relocate, she was forced to live among her detractors, including Philip Smith, a revered lieutenant and one of her accusers on the county court.

When Smith fell ill during the winter of 1684, he knew that Mary had cast a spell on him. “Be sure to take care of me for you shall see strange things,” he told his brother in an account by Cotton Mather, who wrote “!https://faculty.uml.edu/bmarshall/Mary%20Webster.htm#_ftnref5!Magnalia Christi Americana” in 1702. “There shall be a wonder in Hadley! I shall not be dead when it is thought I am!”

As Mather describes in painstaking detail, Smith was overcome with a monstrous illness. Friends and family who surrounded his bed in solidarity bore witness to what Mather called the “evil” among them. Smith insisted that Mary’s specter hovered over him, stabbing him with pins. His medication vanished from the fire. Flames erupted on the bed, but as soon as they were remarked upon, they disappeared. The headboard rattled, no matter how many men leaned against it. There was a constant scratching sound by his feet. Something as large as a cat skittered under the blanket. Smith was delirious throughout.

According to Mather, Smith could only sleep through the night when some of the men “give disturbance” to Mary, like they had in the past. But as he lay on his deathbed, beating her would not suffice. A mob of men rushed to her house to mete out her final punishment.

In 1764, Thomas Hutchinson, in “History of the Massachusetts Bay Colony,” described what happened next: “Having dragged her out of her house, they hung her up until she was near dead, let her down, rolled her some time in the snow, and at last buried her in it and there left her, but it happened that she survived and the melancholy man died.”

In Atwood’s poem, “Half-Hanged” Mary, who lives for another 11 years, is defiant: “surprise, surprise: / I was still alive. / Before, I was not a witch. / But now I am one.”

For a profile in the “New Yorker,” Atwood showed the reporter a box of newspaper clippings from the 1980s – her research for “The Handmaid’s Tale”: “There were stories of abortion and contraception being outlawed in Romania, and reports from Canada lamenting its falling birth rate, and articles from the U.S. about Republican attempts to withhold federal funding from clinics that provided abortion services,” says the article, written in 2017. “In writing [the novel] Atwood was scrupulous about including nothing that did not have a historical antecedent or a modern point of comparison.”

Atwood drew from the past — all the way back to Mary — but Belanger says that we tell ghost stories in service of the future: “As we know, history repeats itself, and we might be better equipped to deal with it next time.”

It’s scary, really, that the same things Atwood was worried about in the 1980s are top of mind for voters heading into this election. Roe v. Wade has been overturned. Project 2025, a 922-page “Mandate for Leadership for the next conservative President” says that “reproductive rights” should be struck from the cultural conversation, or taken “out of every federal rule, agency regulation, contract, grant, regulation, and piece of legislation that exists.” Over and over, the agenda stresses that under new leadership, a woman’s God-given duty is to be “pro-family.” This turn of phrase, which vice-presidential candidate J.D. Vance has employed liberally when asked about abortion, ups the ante of an already fraught conversation, demonizing choosers as indifferent to life and disrespectful of an institution.

“Families are the basic unit of and foundation for a thriving society,” write the authors, the majority of which are men. “Without women, there are no children.”

Maybe Mary chose to be a childless cat lady. She was certainly, unabashedly herself. Unfortunately, she was buried in an unmarked grave in Old Hadley Cemetery, but Weinberg insists that her lack of headstone has nothing to do with her charges — Mary didn’t have money, and in the more than 300 years since her death, there have been many floods in the region. He believes the townspeople saw in Mary a threat to their security, not so much their safety, but the status quo.

“I would not characterize Mary as a witch,” says Weinberg. “I would characterize her as an early feminist.”

Edith Wharton

‘I do not believe in ghosts, but I am afraid of them,” wrote Edith Wharton, the New York-born, Pulitzer Prize-winning author who wrote prolifically at The Mount in Lenox. Raised in the late 19th century and thrust into high society, Wharton was forbidden by her mother to read novels and expected to marry well. In 1885 she married Edward, known as Teddy, who suffered from bipolar disorder. The tightrope she walked threatened to snap.

CONTRIBUTED

In 1901, Edith Wharton designed the sprawling mansion called The Mount and moved there with her husband, Teddy, for the next decade. His illness inspired fits of violence and was deemed incurable. Edith divorced Teddy in 1913 and was the first woman to win the Pulitzer for Fiction in 1921. But it is believed that she frequents The Mount. An article in the Paris Review posits that perhaps she lingers in solidarity with other women — fictional and real — who have had to live with domestic violence.

“She understood the formalized world,” writes Roxana Robinson at the Center for Fiction. “But she also felt the presence of another, unacknowledged one. This one held emotions and ideas, and it seethed around her like an invisible mist.”

In 1901 Wharton designed the sprawling mansion called The Mount and moved there with Teddy for the next decade. His illness inspired fits of violence and was deemed incurable. In her husband, says Belanger, “she would have seen a Jekyll and Hyde, someone seemingly calm at one moment, and completely different in another. You can have the opinion of a medical professional, but you’re not there in the middle of the night when it happens. It seems unnatural.”

Edith divorced Teddy in 1913 and was the first woman to win the Pulitzer for Fiction in 1921. But it is believed that she frequents The Mount. An article in the Paris Review posits that perhaps she lingers in solidarity with other women — fictional and real — who have had to live with domestic violence. “I knew that I had seen a ghost,” writes the author, “but it was none of the apparitions named on the tour. I had felt the real fear of a woman whose only chance to escape an unstable marriage was through the unlikely success of her writing.”

Martha Dwight

In 1788 in Belchertown, Martha Dwight had been buried for six years when she was accused of being a vampire.

Reverend Justus Forward, a Yale-educated doctor, had lost three relatives to tuberculosis, and two more had fallen ill. The minister wrote desperately to a friend, describing how he “had consulted many about opening the graves of some of the deceased, to see if there were any signs of the dead preying on the living.” Vampire scholar Michael Bell explains that this “was not an arcane or arbitrary ritual dreamed up by some sort of weird wizard” — it was an ancient folk remedy thought to be absolutely necessary to the living’s health and safety.

Forward opened up the grave of his mother-in-law, who had been buried for three years, where he found her unremarkable skeleton. Disappointed by her deadness, he pressed on and dug up Martha. Her lungs were full of blood, and the liver was similarly intact. The evil organs were placed in a box and buried in the same grave, about a foot above the coffin.

Dwight, buried at South Cemetery in Belchertown, has never been cleared of murder.

Eunice Williams

In February of 1704, Eunice Williams had just given birth to her seventh child. Her husband John, Deerfield’s minister, had a vision that the town would be destroyed, and on Feb. 29, 300 French and Indigenous warriors began a massacre at the Williams’ house, killing their 6-week-old daughter and 6-year-old son. By morning, 112 Deerfield residents were taken captive, including Eunice, who was in no state, physically or emotionally, to make the trek north.

Photo by Frank Grace

The Eunice Williams Covered Bridge, also known as The Screaming Bridge, in Greenfield.

On March 1, as the group waded through the ice-cold river in Greenfield, Eunice collapsed from exhaustion and was executed in front of her remaining five children.

In 1870, a bridge was built in her honor, a sort of memorial over the river. “Now it’s called the Screaming Bridge,” says Belanger, “because it ties into her final death scream.”