By CAROLYN BROWN

Staff Writer

Peter Gizzi, professor of poetry at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, recently won the 2024 T.S. Eliot Prize for Poetry, one of the world’s most prestigious poetry awards.

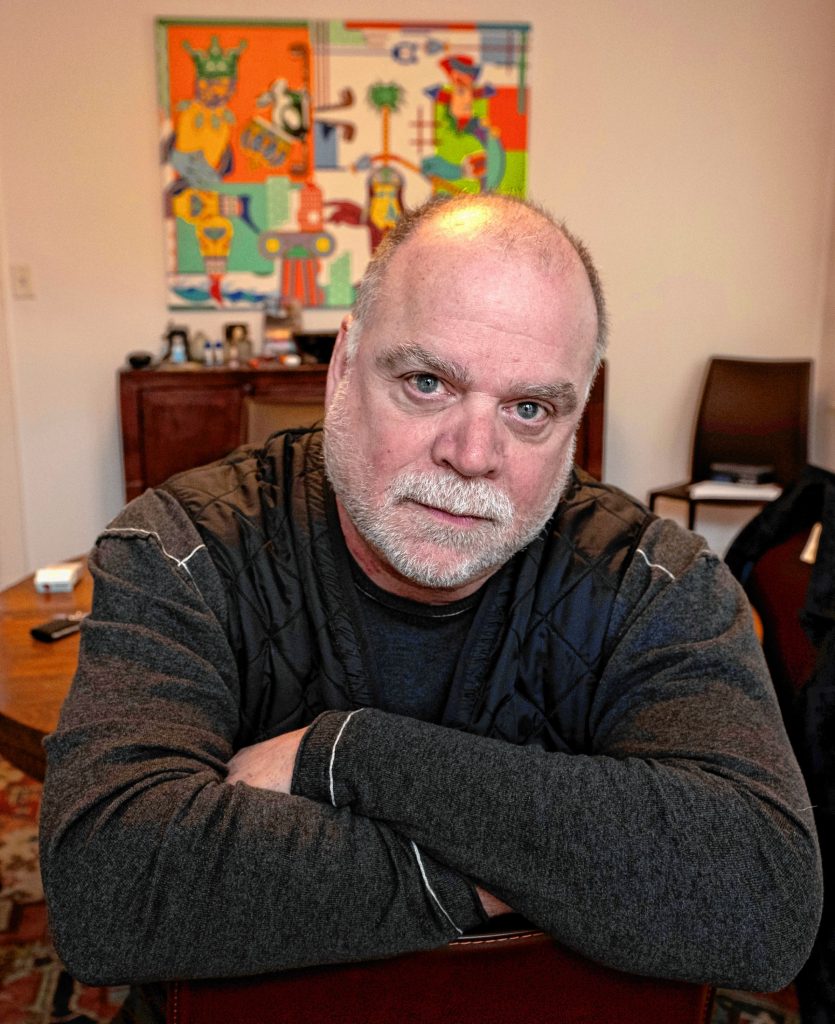

STAFF PHOTO/CAROL LOLLIS

UMass poetry professor Peter Gizzi won the 2024 T.S. Eliot prize for poetry. A self-described “New Englander through and through,” Gizzi currently lives in Holyoke but grew up in Pittsfield: “The Berkshires, to me, made me. If you want to locate a place inside me, it’s the Berkshires.”

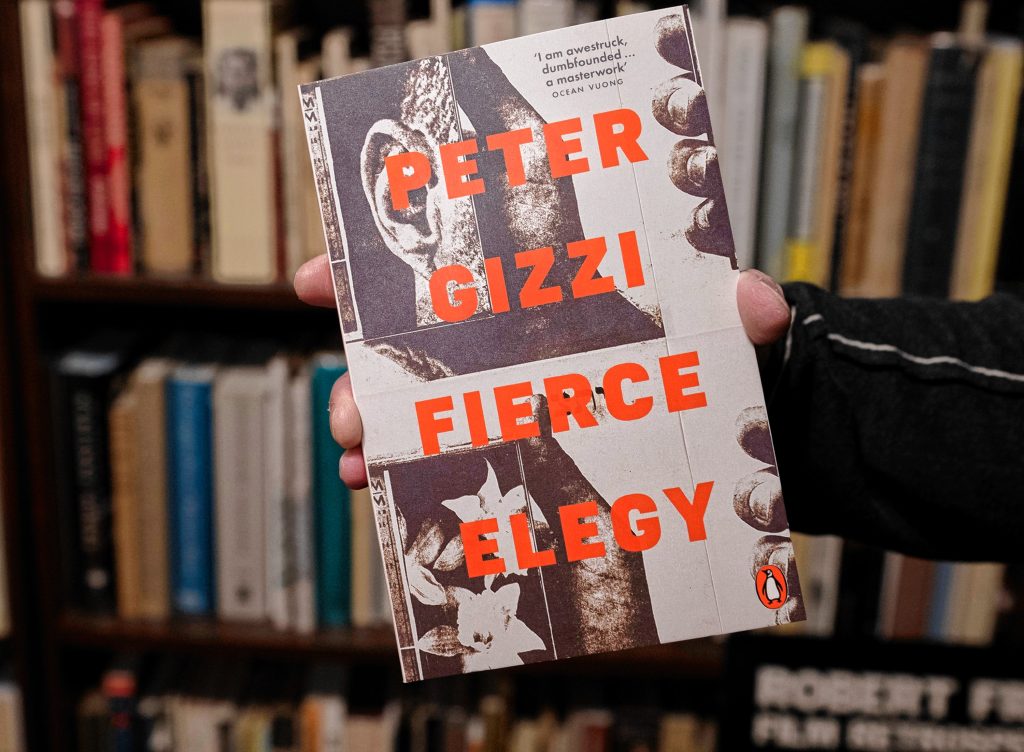

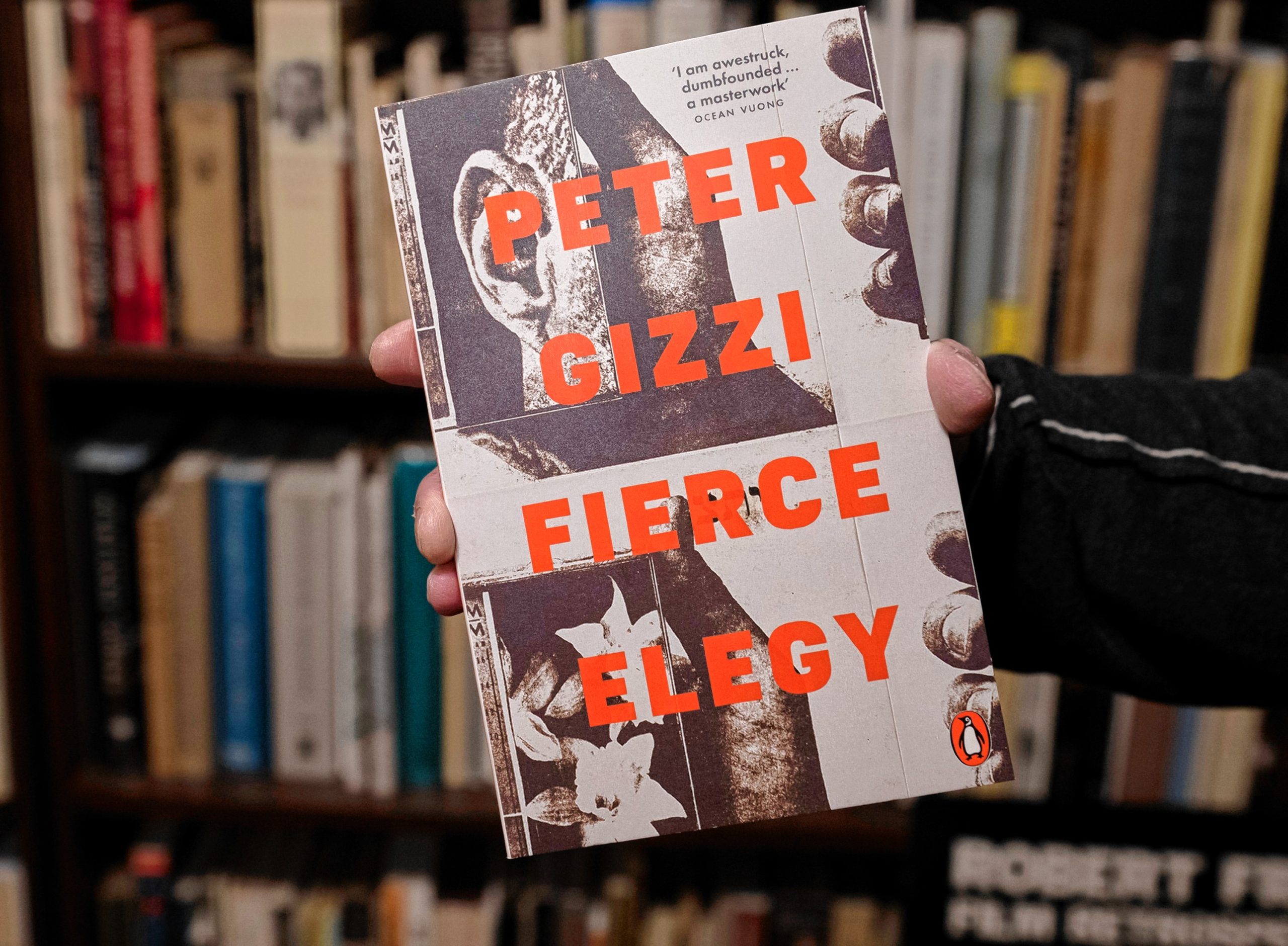

Gizzi’s book “Fierce Elegy” beat nearly 200 other competitors to take home the prize, which Gizzi accepted at an award ceremony at the Royal Festival Hall in London on Monday, Jan. 13. He is the second UMass Amherst faculty member to win the award: Ocean Vuong took home the prize in 2017 for his debut collection, “Night Sky with Exit Wounds.”

Judge Hannah Sullivan, delivering a speech on behalf of judge chair Mimi Khalvati, said that “Fierce Elegy” is “a breathtaking book-length sequence in which each line or sentence, often paratactic, non-hierarchical, could be a poem in its own right. As if wordings had been gifted to him out of the ether, one-liners, two-liners coalesce into love lyrics, or a thought enters his head which, step by step, he unravels until a nucleus is reached and pierced.”

“I had zero expectation of getting this thing,” said Gizzi. “I was just happy to be a finalist. All I really wanted to do was put my work over and give a really good reading.”

Still, not everyone in the poetry world appreciated the win: The Telegraph bluntly declared that the award went to “the wrong man,” and The Times called out the judges for going “back to male, pale, and stale” with a “tedious” and “flatulent” book “unworthy of the accolade.”

The criticism didn’t bother Gizzi, though.

“I could give a [expletive],” he said. “I think it’s really funny.”

STAFF PHOTO/CAROL LOLLIS

Peter Gizzi holds his book, “Fierce Elegy,” for which he won the 2024 T.S. Eliot Prize for Poetry. The book took so much of its inspiration from Gizzi’s own losses.

As someone who didn’t grow up in an erudite, poetry-heavy background — as he puts it, “I come from the wrong pedigree” — Gizzi wasn’t surprised that some British critics were derisive about the award going to an “unwashed American.” Even his personal favorites are “outsider,” to some degree: “The poetry that I’m interested in, I would call a counter-tradition. It’s definitely not the big award-winning poets. Mostly, the poets that have informed my entire life, they’re not under-the-radar, but they’re not Louise Glück, if you know what I mean.”

A self-described “New Englander through and through,” Gizzi currently lives in Holyoke but grew up in Pittsfield: “The Berkshires, to me, made me. If you want to locate a place inside me, it’s the Berkshires.” He considers it “a great honor” to be back in his home state educating Massachusetts students, “reaching down and pulling them up and giving them permission … That’s amazing. That’s the prize.”

That rewarding life has not come easily.

Grief has played an outsized role in Gizzi’s life. At the age of 12, he lost his father in a plane crash, which he and his mother watched on television. He’s since, as he put it, “helped my entire family of origin cross over. I’ve lost a lot of people.”

“I grew up with a native understanding of irrevocability,” he said, “and what does that do? It gave me eyes to see. It let me see in a much larger way and a deeper way. It also allowed me to not ever judge anyone’s suffering, but only to witness it and embrace it. But it also allowed me to see the small joys that compose a life, and how those small joys actually are massive.”

Grief also plays an outsized role in Gizzi’s poetry. An elegy is, after all, a lamentation, and “Fierce Elegy” took so much of its inspiration from Gizzi’s own losses. In the poem “But the Heart in a Sense Is Far from Me Floating Out There,” Gizzi writes: “Hold on to the afterlife of the beloved, it’s the / only thing that’s yours.”

“Joy and sorrow, they share a very complex ecosystem. They’re actually one thing. As the world becomes constantly renewed, it’s also constantly dying, and I’m interested in having both,” he said. “What I’ve discovered is there’s a majesty to grief. What I mean by that is, it allows me or us to finally understand the mystery of being. And that’s a joyful thing, right?”

“As long as there’s been soldiers, there’s been poets,” he added. “We’ve been here forever, and the lament or the elegy is the primary modality of understanding reality — that nothing is here forever. I just feel like poets have been writing through one rotten kingdom after another from the beginning. Look where we are today — hello?”

In Gizzi’s early career, during the Bush administration, he spent a lot of time writing poems in response to news stories, as “the volume of the world” kept getting louder. After a time, though, he decided he no longer wanted to write about world events, but, instead, to make his work more personal — to “bring the lens closer to me.”

“I believe there’s this deep well, and when I write, I connect to this thing. It’s bigger than me, it’s older than me. It doesn’t live in me, I live in it. It rents me, and I’m good with that,” he said.

After all, why make poems about news if poetry itself could serve as a chronicle in its own right?

“Poetry is the human record,” Gizzi said, “because what we write about and what we witness is intimacy. We have found a proper way to say goodbye. We have found a remarkable way to pronounce love.”

Now that he’s won this big award, there’s prize money to spend — about $31,000 of it (£25,000), to be specific — and Gizzi plans to use it to fix his roof. After that, though, what’s next — another book? Another poem?

Not yet: Gizzi says he hasn’t written in over a year, but he’d need inspiration first if he did.

“I’m waiting for the next phrase,” Gizzi said. “This is how I write a book: I have to catch one phrase, and that phrase has to be big enough to create an environment and a horizon of meaning that I can occupy.”

Even though Gizzi just received one of the highest accolades in his field, he still approaches the win with a sense of humility. Winning a prize like this, he said, while an incredible honor, won’t change much in his day-to-day life: “You read to 2,500 people, and then you’re back home alone in your bathrobe.”

“It’s in times like this that I am keenly aware that this is merely God’s way of embarrassing me. We both know that I could be better, and that I’ve spent my life serving this magnificent form of human utterance,” he said. “I really believe that poetry — man, it’s everything. It’s total for me.”

Carolyn Brown can be reached at cbrown@gazettenet.com.