By DON STEWART

For the Valley Advocate

A century ago, when women could be arrested for smoking in public and the manufacturing and distribution of alcohol was illegal, there was an artistic and social revolution in this country. You can view a wealth of Jazz Age posters, paintings, illustrations and accouterments at Stockbridge’s Norman Rockwell Museum through April 6.

Historians mark the era as beginning in 1919 and it’s lost to the fogs of time as to when it ended.

“It depends on who you ask,” Heather Coyle said during a press reception. “F. Scott Fitzgerald said that once the money stops, 1929 is the end of the Jazz Age, but I find that there’s a continuation of a lot of the themes into the 1930s.”

The stock market crash in October of 1929 brought many things to an end including a shaky economy and the eventual collapse of some 9,000 banks.

Coyle is the curator of American Art at the Delaware Art Museum where this exhibit premiered last year. She also edited and contributed to the show’s companion catalogue “Jazz Age Illustration” (Yale University Press; 176 pgs; $50.)

The curator cast a wide net in assembling these works, many from private collections, ranging from Erte and Rockwell Kent to the illustrations of J.C. Leyendecker and celebrity artist John Held Jr. Amidst these images there’s also a video displaying the dance moves of Josephine Baker, the Nicholson Brothers and the musician Cab Calloway.

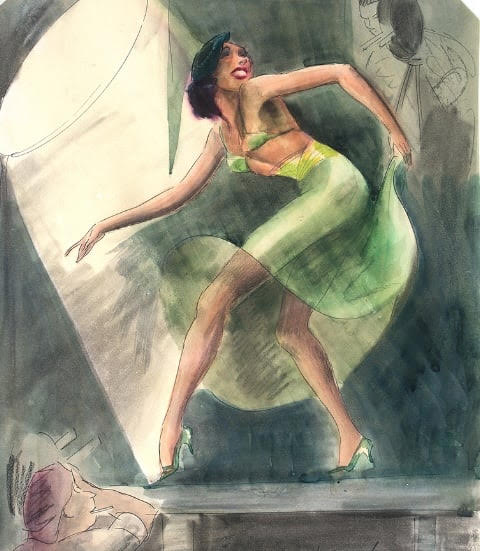

Before entering the museum you’ll see a life-size 1940 watercolor of Etta Barnett, an African American whose contralto voice brought her fame. When George Gershwin scored the original “Porgy and Bess,” he wrote the female role specifically for her. Barnett’s vocal range was so broad that in films she often dubbed the songs of White actresses.

Etta Barnett was a university instructor, then a film actress and singer. In retirement she became a civil rights activist and lived to age 102. “Etta Moten Barnett Dancing” by Jay Jackson. DELAWARE ART MUSEUM / Courtesy

“We wanted to tell a big story about American illustration at a time when it was such a big deal, “ Coyle said. “(It was) an important force in reaching America and telling a story that really shaped and reflected the culture.”

A renaissance

Etymologists note that the word “jazz” is found around 1912 in baseball slang to mean pep or energy. A short time later, newspapers are informing readers as to a new form of music with its origins among Black musicians in the South. Its epicenter was New Orleans. An original and revolutionary music form which defined freedom in every note, it became a gift to the world.

In 1922, Fitzgerald wrote a collection of best-selling short stories titled “Tales of the Jazz Age” and, as Coyle said, in giving the era a name “that cemented it.”

For the East Coast, the cynosure of this new age was in New York, where, in a three-square mile neighborhood of 175,000 African Americans, what would become known as The Harlem Renaissance was blossoming. Hundreds of thousands had left the South for the northern cities and in many communities, like Harlem, they had their own publishing presses.

“Suddenly there’s a place for Black stories to be told,” Coyle said, “and to be illustrated by Black artists.”

There are examples of those magazines in one gallery, ranging from the militant “Fire” to “Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life,” the periodical of the National Urban League.

Among the pioneers of the Renaissance was the artist Lois Jones. Later a Howard University instructor, she was among the first to create children’s books featuring Black youth at play. There are several highly detailed, joyful renderings of her work here.

“Harlem becomes this huge entertainment district,” the curator said. “Many of the clubs there are patronized by Whites, but the entertainment is by Black artists.”

There were a half dozen clubs catering exclusively to the “class White trade.” There were hundreds of other venues as well. You could find Calloway at the Whites-only Cotton Club and nearby, Duke Ellington’s band and tap dancer extraordinaire, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. A blowup of E. Simms Campbell’s 1932 guide to Harlem after dark suggests that at one watering hole “nothing happens before 2 a.m.”

Visiting these nightspots you’d never guess that alcohol was illegal. Feeling adventurous? If you had a seaworthy craft there were hundreds of boats up and down the coast, outside the three-mile limit, where booze also flowed.

New printing technology raised commercial artwork to a new standard in the 1920s. A 1922 cover of a Marshall Fields fashion catalogue. “Springtime” by Joseph Bolegard. DELAWARE ART MUSEUM / Courtesy

A sea change

The revolution was both in technology and sexual mores. The first national radio broadcast was in 1920, when some two million households owned radios. By the end of the decade that number quintupled and in 1930 cars now featured radios. Jazz had become transportable.

Another remarkable breakthrough was in the creation of full-color printing, freeing illustrators from a relatively crude three-color process.

Print media now sparkled with a full palette and for advertisers selling anything from soap to silverware the painted images approached middle, if not high art. National magazines, such as “The Saturday Evening Post” and “Vanity Fair” allowed advertisers to reach all 48 States. Advertising became big business and by 1925 $1.2 billion was spent domestically on the art of selling.

As Coyle explained, many ads were now running with the idea of subtle lifestyle aspiration. A delicate pastel by Neysa McMein, considered to be a self-portrait, is of a chic woman in a black, open backed, slinky dress clutching her necklace. The ad is for Wallace Silver, yet not even a spoon is to be found.

“She looks like she doesn’t give a damn about silverware,” the curator said. “But she’s going to throw a great party.”

As you look at these illustrations you find that the sharp-angled line work of Art Deco, a new art discipline transported from Europe, frequently appears. With the discovery of King Tut’s tomb in 1922, Egyptian motifs also became a craze among the era’s illustrators.

Coyle spoke about another seismic change. Women had joined the work force in great numbers during a labor shortage during WWI and remained. In 1920, after decades of struggle, they could now vote, opening new freedoms.

For young women in their teens or early 20s, there was the stereotypical “Flapper” image. With hemlines traveling further north than ever before in slinky dresses, rolled stockings and dangling necklaces, it was enough to give their parents the vapors. The shock of shocks was that they often bobbed their hair, cutting it quite short.

“It’s hard to imagine what a big thing that was,” the curator said. She explained that in researching newspaper morgues for the exhibit she found a startling headline.

“Woman Cuts Hair – Fiancé Throws Himself Off Bridge!”

“Literally,” Coyle said. “It was that big of a sea change.”

The curator pointed out her favorite painting wherein the artist, William Raine, depicts three people on a snowy mountain road. The 1925 oil, created for a story in “Woman’s Home Companion” told of a flapper and her boyfriend, their car stuck in the snow. Their clothes are inappropriate for the weather and they are to be rescued by, as the curator said “a steady, sturdy man,” a former flame. Coyle said this was a typical story arc at the time. The sophisticated, citified woman finds, like Dorothy in Oz, that there’s no place like home.

It was the multifaceted artist John Held Jr. who best satirized the wild parties and carefree sexuality of the time with his cartoonish renderings. His subjects had heads reminiscent of Ping Pong balls and easily contorted elastic bodies. You’ll find his work in the galleries including a poster outlining where to find fun in the Berkshires.

For many, however, there was no elation, but grave concern. Coyle said that, for an older generation, “there was a sense of moral collapse and jazz with its new rhythms, new improvisations and syncopations made people nervous.” The curator found that as early as 1919 a minister in Philadelphia spoke about “the dangers of this moment and how jazz is just emblematic of this moral looseness.”

Somehow America survived. However, as Fitzgerald noted, the money stopped. Wall Street lost $14 billion in value in a single day in 1929 and soon after, one out of four American workers was unemployed. The Jazz Age slowly evaporated like flat Champagne.

“Jazz Age Illustration” continues at the Rockwell through April 6. In a lower gallery the works of the late Berkshire artist Deb Koffman continue through June 8. The museum is closed Nov. 27, Dec. 25 and Jan. 1 and closed on Wednesdays during the winter months. The museum is open Monday-Friday, 10 a.m.-4 p.m., and Saturday and Sunday, 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Admission $25; Ages 18 and under, free.