Dying City is one of those plays in which secrets and mysteries get unraveled bit by bit in high-octane confrontations and confessions. But at the end of Christopher Shinn's highly lauded play (a Pulitzer finalist last year), when all the plot threads were spun out and the home truths laid bare, I was left with one overwhelming question: So what?

Wilson Chin's set for the Hartford Stage production reflects the play's layered reality. A huge multi-paned window, tilted toward the sky, dominates the sparsely furnished living area of a New York apartment. Sometimes it frames a geometric cityscape silhouetted against an angry red sky. Sometimes Traci Klainer's subtle lighting turns the window into a mirror reflecting the action below it. And ultimately the skyline is revealed to be constructed of piles of cardboard boxes.

Which is the play's opening image, too. A young woman, Kelly, is packing books into a corrugated box, which she hides when Peter shows up unannounced. Kelly is the widow of Peter's identical twin, Craig, killed a year before in Iraq. How it happened is the most transparent of the play's puzzles.

Craig was an unlikely soldier, a student of literature who used ROTC to put himself through Harvard, but was then caught up in active duty in Iraq. (Although the play's title is partly a reflection of post-9/11 New York, the phrase "dying city" comes in an email from Craig, referring to Baghdad.)

Unfolding in a single 80-minute act, the play skips back and forth in time. It opens on the first anniversary of Craig's funeral, then shifts to the last night before Craig shipped out to Iraq. In those flashbacks, we see a troubled tension between Craig and Kelly, which Peter's unwelcome presence only aggravates.

Peter is an actor on his way up, a cocky young man who signals his self-importance with phony disparagements of his latest film (a war movie). Right now he's in a Broadway play, and has just stalked out of the theater in the middle of a performance after a fellow actor mocked him with a homophobic remark.

I think the playwright made Peter gay partly to provide a contrast with his straight, married brother, and partly to remove any suggestion of sexual attraction between him and Kelly. Mind you, sexual habits and hang-ups play a role here, but the burning question isn't "Will these two get together?"

It's no coincidence, dramaturgically speaking, that the play Peter is appearing in is a revival of Long Day's Journey into Night. Both Eugene O'Neill's masterpiece and Dying City are family dramas fraught with smoldering resentments, lies, self-deceit and self-hate.

This play is as modern as today's headlines, but frustratingly old-fashioned in its passive sexism. While it revolves around Kelly's relationships with the two brothers, she's not really an actor in the drama, but a reactor to what the men say and do, and her profession—a psychotherapist—is little more than an excuse for a rather sick running gag.

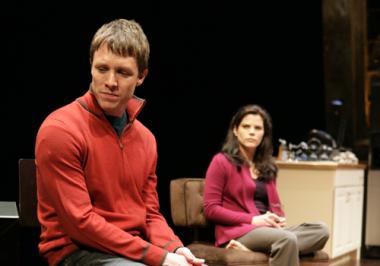

That said, Diane Davis gives Kelly plenty of juice. She's smart, passionate and fiery, and the way she interacts with the two brothers tells us more about them than Ryan King's performance does.

King plays both men, slipping offstage as one brother and reappearing almost immediately as the other one in sometimes seamless time-transitions. He has the challenge of differentiating two characters who, of course, look exactly alike. He's not helped by the script, which makes little effort to distinguish their dialogue, but he also doesn't do much to make them physically or vocally distinct.

Dying City is all about unwrapping the layers to uncover painful truths and solve the mystery—like the episodes of Law and Order Kelly is obsessed with. And like a pulp fiction police procedural, at the end, everything is known but the characters and their lives aren't significantly changed. The shattering revelations don't affect the trajectories Kelly and Peter were on at the beginning. Peter's career and complicated love life continue as before, the backstage crisis is resolved, and the play ends as it began, with Kelly sadly packing away her husband's books."

Dying City, by Christopher Shinn, directed by Maxwell Williams, through Feb. 8 at Hartford Stage, 30 Church St., Hartford (860) 527-5151, www.hartfordstage.org.

The Belle of Holyoke

"I choose to be the one," said Belle Skinner. And she was—the one who "adopted" and rebuilt a shattered French town after World War I; who established a cafe/refuge for women working in Holyoke's silk mills; who epitomized Gilded Age glamour but tempered it with a spirit of charity.

And that typically firm statement is the title Ann Maggs chose for her one-woman performance, based on Belle Skinner's letters and diaries and performed in the Skinner family's mansion, Wistariahurst. Built by Belle's father, William Skinner, whose silk mill was a fixture of 19th-century Holyoke, the building is now a city-owned museum.

Maggs' performance, a first-person visit with Belle Skinner, takes place in two of the house's formal spaces: the classical-columned Music Room, and the Great Hall, dominated by a grand curving staircase—designed, we may imagine, for Belle to make the impressive entrances she was fond of.

I Choose to Be the One, Jan. 23, Wistariahurst Museum, 238 Cabot St., Holyoke, (413) 322-5660.