Two-Headed

By Julie Jensen, directed by Marc Geller. Through August 18, Berkshire Theatre Festival, Stockbridge, (413) 298-5576.

In September 1857, a wagon train bound for California camped in southwestern Utah near a Mormon settlement. The fanatical and paranoid Mormon militia decided the travelers were connected to persecutions of the Latter Day Saints in the Midwest a dozen years earlier. In what came to be called the Mountain Meadows Massacre, more than 120 men, women and children were slaughtered. This event provides the starting point for Julie Jensen's engrossing two-character play, and it reverberates throughout her narrative.

We meet Lavinia and Hettie when they are 10 years old, and follow them, in five short scenes, through five decades of their lives in the Utah Territory. In the process, we witness not only the arc of a lifelong relationship, but also the workings of early Mormonism seen through these women's very different attitudes toward it.

Lavinia (Corinna May) is capricious and irreverent, a rule-breaker who mocks the pious hypocrisies of the Mormon church. Hettie (Diane Prusha), shy and stolid, obediently follows the faith and her closed society's expectations. Lavinia's impertinence offends Hettie, and Lavinia calls Hettie "stupid as a stump." Lavinia's father was involved in the massacre, and she's tortured by the knowledge, but Hettie defends it as an act of justified revenge. They don't approve of each other, but in a life dictated by men and circumscribed by a self-righteous cult, they're all they've got.

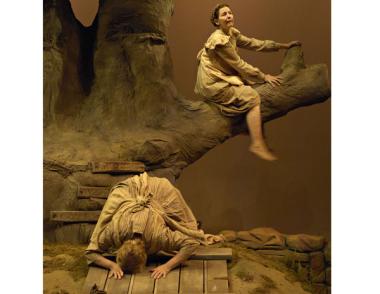

The performers, both veterans of Shakespeare & Company, perfectly embody their characters. May is wiry and abrupt, while Prusha uses her soft, comfortable body to give Hettie the slow-moving and slow-speaking manner that others take as slow-witted. Both women are utterly convincing, aging 40 years in the course of the 70-minute play. May, however, is positively mesmerizing. She's sharp, mercurial, steely-eyed and acid-tongued, then, as Lavinia is progressively hammered by events, we see the layers of insouciance rip away, and it's heartbreaking.

Julie Jensen is descended from participants in the Mountain Meadows Massacre, and she's fascinated by the guilt and denial that persist to this day. She also delves into the legacy of the Mormons' "divinely inspired institution of plural marriage"—i.e., polygamy.

"Plig," as Lavinia terms it, affects each woman's life course and, in the process, wrecks their friendship. First Hettie marries Lavinia's father—to "finally be the equal of you," she tells Lavinia. Then, 20 years later, Lavinia's husband takes Hettie's daughter as his second wife. These twisted relations serve not only as an indictment of perverted doctrine (and patriarchal privilege) but as a kind of metaphor for the sometimes painful convolutions of longtime relationships.

On Aaron P. Mastin's impressionistic set, a large tree, its ponderous branches worn smooth from years of children climbing it, stands above the door to a subterranean root cellar. The tree and the cellar door are also metaphorical, one a lookout onto the wider world, the other a place of dark secrets. Dennis Ballard dresses the women in dull-colored homespun skirts and smocks that blend with the dirt beneath them.

The play's title refers, initially, to a two-headed calf that 10-year-old Lavinia, tantalizing Hettie, says is tied up in the root cellar. It also refers to the two women themselves, so different in temperament and outlook, who are nevertheless bound together by circumstance and eventually by blood. In a sense they are two parts of the same person, divergent products of the same culture, torn between instinct and duty, each seeking to make sense of the horrible event that shaped their childhood and shadows their lives?