Last year, I asked my then 11 year-old pal Emily where she wanted to go to college and she answered, “Smith, because I know my way around the campus already.” She made a good point; the campus is in our neighborhood.

This week, I asked Saskia what she wants to be when she grows up. I like to keep up on these things, you know, being her mum and all. She answered, “Firefighter.”

Her aspiring chef now-teenage brother wanted to be a firefighter at four, too. What will she want to do at 13? What will they both want at 23? Or 33? Stay tuned.

**

All this to say, I want to give nods to feminist young-kid related writing I came across this past week:

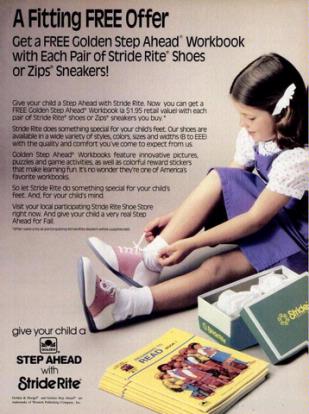

- On her blog, Peggy Orenstein wrote a fantastic post about sparkly, glittery shoes and the way advertising to young girls about their footwear has more to do with how you look in the shoes than playing these days, a change from days when the idea that young girls (and boys) got play shoes—aka sneakers—in order to play.

- Orenstein ties this sneaker musing with smart observations made by K.J. Dell’Antonia on Motherlode, where she links young kids and obesity to young girls and lack of outdoor play (not rocket science, but then add in the diet industry, something highly profitable and equally ineffective). Thankful today for articulate feminist mama writers who tease out glaring truths.

- There’s more common sense with Jessica Valenti’s take this week on why she wants to like President Barbie, but can’t. She notes careers are, optimally, based upon interest rather than wardrobe—at least she’d like this to be the message she shares with her daughter. Additionally, I must note her warranted skepticism about this being the very first Barbie with the ability to stand on her own feet. It’s 2012, people.

Maybe Addy’s not dressed for playing in the dirt.

Wardrobe change. Shoes off, save for Saskia’s glittery ones.

**

In real life, I’ve had one of those consuming stretches as a parent—a mother, a feminist mother—that reminded me again what I do as a parent—a mother, a feminist mother—is devote more energies to these relationships with my brood than I’d imagined I would. It’s emotion consuming and time consuming and the freight of a choice to invest like that in others, including the truth, that at times you probably must question your choices since that allotment of time and energy presumably has affected others you might have made. To be completely honest, sometimes that truth can be crushing.

Intellectually and politically we know that motherhood can be a gateway to financial insecurity and/or poverty. It is, at least at times, many times, exhausting. As Andie Fox of Blue Milk pointed out in a post of hers that links to another, sometimes the truth about motherhood is five minutes’ peace is elusive: “What this means is that when you’re caring for an infant, you can get completely lost in caring for an infant, but you can’t get lost in any other type of work or leisure or relationship or anything else at all. You can try, but you’ll probably be interrupted 30 seconds, or a minute, or five minutes, or sweet glory! an hour! into it.”

The mother to a feminist preschooler wants only for wonderful daughter to be sparkly and strong, stylish if she wants to be, but ready for the substance of career and parenthood as she chooses. The point of a feminist childhood for the daughter and the sons is to give them the ability to dream and to dare. I won’t warn against firefighters, even if I’d be a wreck every single time I heard a siren.