So remember, when you're feeling very small and insecure,

how amazingly unlikely is your birth,

and pray that there's intelligent life somewhere up in space,

'cause there's bugger all down here on Earth.

(Monty Python, The Meaning of Life)

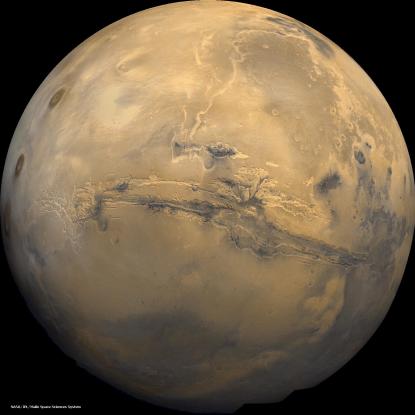

Methane on Mars points to a compelling case for life existing there now or in the past. Even the careful scientists of NASA, who are, as I type, fielding questions from the press, are saying it's time to look for the real deal. That discovery would be a beautiful thing. A little transcendence could help all us wandering apes down here.

Hot Icicles

I was going to limit my post to the circuit-frying defense of torture Joe Scarborough just offered. It encapsulates everything screwed up about apologists for morally reprehensible policies. His "arguing" is reductive and belligerent; he insults his opponent rather than engaging the actual counterargument; and he cannot (or more likely will not) wrap his bacony brain around nuance–as even the Army Field Manual maintains, torture doesn't yield reliable information:

"The use of force, mental torture, threats, insults, or exposure to unpleasant and inhumane treatment of any kind is prohibited by law and is neither authorized nor condoned by the US Government. Experience indicates that the use of force is not necessary to gain the cooperation of sources for interrogation. Therefore, the use of force is a poor technique, as it yields unreliable results, may damage subsequent collection efforts, and can induce the source to say whatever he thinks the interrogator wants to hear."

So why bother? And that's before you get to what it does to the torturer who gives up his soul in search of information that probably won't help anyway. Why would that be worth it when subtler methods have proven far more effective, as interrogators tell us?:

Writing under the pseudonym of Matthew Alexander, a former special intelligence operations officer, who in 1996 led an interrogations team in Iraq, has written a compelling book where he details his direct experience with torture practices. He conducted more than 300 interrogations and supervised more than a thousand and was awarded a Bronze Star for his achievements in Iraq. Alexander's nonviolent interrogation methods led Special Forces to Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi, the head of Al-Qaeda in Iraq. His new book is titled How to Break a Terrorist: The US Interrogators Who Used Brains, Not Brutality, to Take Down the Deadliest Man in Iraq.

"It's extremely ineffective, and it's counterproductive to what we're trying to accomplish," he told reporters. "When we torture somebody, it hardens their resolve," Alexander explained. "The information that you get is unreliable … And even if you do get reliable information, you're able to stop a terrorist attack, Al-Qaeda's then going to use the fact that we torture people to recruit new members."

But nevermind. Scarborough knows better than the people who actually do this stuff, so let's go with him instead.

Anyway. It gets too tiresome, because one might as well argue with the wind, and there is hope for some change at hand. So here's something far more interesting. And it's the product of embracing the complex nature of reality. This is a video from NASA of a cryogenic rocket engine that produces tremendous heat from tremendous cold. While the exhaust is hot, the end of the process yields strange icicles around the bottom of the supercooled rocket cone. And such is the reality of the actual world–full of counterintuitive nuance. It's strangely meditative to watch this process in action.