On October 17 and 18, 2014, the Northampton Academy of Music Theater will debut the new play, Nobody’s Girl, a screwball-style comedy based on a true story from the early 1940s. The events involve Mildred Walker, a cashier at the Academy (then a movie theater), who was promoted to Manager when the Academy’s longtime manager was suddenly called to military service. The men leasing the Academy attempted to oust her, Mildred and the Academy’s Board resisted, accusations flew – and the case ended up in court.

On October 17 and 18, 2014, the Northampton Academy of Music Theater will debut the new play, Nobody’s Girl, a screwball-style comedy based on a true story from the early 1940s. The events involve Mildred Walker, a cashier at the Academy (then a movie theater), who was promoted to Manager when the Academy’s longtime manager was suddenly called to military service. The men leasing the Academy attempted to oust her, Mildred and the Academy’s Board resisted, accusations flew – and the case ended up in court.

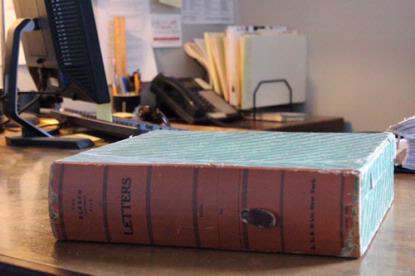

This long-forgotten incident came to light when staff at the Academy stumbled across an old box marked “Letters,” hidden beneath a desk and apparently unopened for many years. Inside was an extraordinary trove of memos, letters, affidavits, and telegrams that traced the outlines of the story, and inspired Debra J’Anthony, Director of the Academy of Music, to commission playwright and UMass Theater professor Harley Erdman to write a play on the topic.

Erdman recently answered a few questions about the project.

When were you approached to write Nobody’s Girl, and what excited you about doing so?

Debra approached me almost exactly two years ago. We had lunch together at a cafe in Amherst in which she explained the project, and at the end of the lunch she handed me a file of photocopied documents. I took them home and read them that same evening. Immediately I got excited about writing a play. There was conflict, colorful characters, great period-specific language, the clear arc of a story. But most of all, my curiosity was piqued because the documents in the file didn’t tell the whole story. There were huge gaps, much was left unsaid. I had a thousand questions, and as an artist I recognize that uncertainty as a good thing. Having questions is what inspires me to throw myself into a project, to research it obsessively, to engage my imagination. You need that intense curiosity, that desire to know, to stay in love with a project for a few years.

explained the project, and at the end of the lunch she handed me a file of photocopied documents. I took them home and read them that same evening. Immediately I got excited about writing a play. There was conflict, colorful characters, great period-specific language, the clear arc of a story. But most of all, my curiosity was piqued because the documents in the file didn’t tell the whole story. There were huge gaps, much was left unsaid. I had a thousand questions, and as an artist I recognize that uncertainty as a good thing. Having questions is what inspires me to throw myself into a project, to research it obsessively, to engage my imagination. You need that intense curiosity, that desire to know, to stay in love with a project for a few years.

What was the film company’s main complaint about Mildred? Did they try to oust her because she was a woman?

It’s hard to boil it down to one thing. Sexism was certainly front and center. They basically said they did not believe a woman could handle the job. But there also were issues of power — they wanted to appoint their person, not the Board’s. There were issues of class, given Mildred’s background. She was working class, had been a cashier her entire working life. There were issues of regional/national control versus local control: who was going to call the shots at this theater? Ultimately, these issues intertwined in complex ways, and my play attempts to acknowledge that complexity. There is moral complexity and ambiguity too. Mildred was accused of double-selling tickets — basically, fraudulent business practices. My play grapples with these accusations as well.

What were some of the most interesting things you discovered about Mildred in doing your research?

From people who had personal reminiscences of her, I discovered fascinating tidbits: that she drove a Cadillac (not very typical in unflashy Northampton in those days). That she wore high heeled shoes and so you could hear her coming from the next room. That as a girl growing up in Northampton, her family had a different address almost every year — a sign of the transient, difficult circumstances of her family. Her father was a menial laborer, frequently unemployed, and it seems she was her family’s main means of support. Also, that a bit later in her life, if not at the time of the play, she was having an affair with a married man, a photographer who had worked as a projectionist at the Academy. He divorced his wife a few days before he married Mildred!

The play is described as a “screwball comedy.” Did you start out making it a comedy?

I don’t try to write “laughs” per se, but the material lent itself very readily to screwball comedy, which is a film genre exactly of that period (early 1940s), and the Academy, after all, was exclusively a movie theater at the time. Screwball comedies usually feature gender inversion — a powerful, witty woman linked romantically with a “feminized” man. They feature a world in which all the characters, even minor ones, are off-kilter. They feature distinctly American rhythms, speech patterns. All these qualities were there in the files. Screwball comedy, which was actually Debra’s idea, just felt right. That said, it’s not a “pure” screwball comedy. It’s an original play with screwball comedy elements. Call it a play inspired by screwball comedy.

What makes the play relevant for audiences today?

The circumstances and characters are fascinating, outrageous, funny, and still deeply relevant to the world we live in today. It’s the story of a woman of “moxie” who hit up against the glass ceiling of her time. Nobody’s Girl is rooted in my belief that even forgotten people with ordinary lives are involved in “making history.” Mildred, little-known even in her time, in some way made a difference. In her own imperfect way she was a hero, I hope my play attests to the dignity and value of her struggle. That struggle is still with us.