If you were a child living in Coleraine, Massachusetts, from 1840 to 1890, you would have been a witness to and a participant in America’s industrial revolution. Though the production of apples, honey, and maple syrup would continue to dominate the local farm economy, in 1828 Joseph Griswold, a native of Buckland, impressed by the industries he observed in the West, determined to create an industrial future for his family and community. Located on the North River in Coleraine, Griswold’s first business was the manufacture of sashes and blinds for windows.

In 1832, after observing the success of the Adams cotton manufacturers where he sold his second line products, gimlets and augers, he built his first cotton mill purchasing a “Lowell loom” using its castings as patterns for other looms, manufactured at Daniel Willis’s Foundry Village in Coleraine. By 1865, this part of the town had became known as ”Griswoldville” boasting more than 100 looms, and Joseph Griswold had built another mill at Willis Place.

Together the two mills would employ over 200 workers, including native farmers, neighboring townspeople, and French Canadian immigrants who Griswold sought out in 1870 and hired as part of a “family system” where the whole family was not only employed as workers, but lived in company housing and purchased their coal and staple goods at the company store. If you were a child in Colerain and were from a farming family, you were likely to attend one of nineteen schools in the town and you might work in the mills. If you were a child from a French or other immigrant family, you would work in the mills, and might also attend school.

Although we are apt to look critically at child labor today, we need to remember that farm children have always worked on their family farms. In the nineteenth century, although they had breaks from their tasks, boys worked with their fathers and learned planting, harvesting and construction, especially carpentry. Later in the century, if his family were prosperous, he might learn machine operation, maintenance, and repair as well. On a daily schedule, boys would rise early to help with the feeding of animals, chopping wood, and drawing and hauling water before breakfast. The girls worked beside their mother where daily tasks included cooking three meals, washing dishes and pots, and tending to small children and the kitchen garden. Depending on the day and season, girls would assist their mothers with laundry and ironing, sewing and mending, baking, making candles and soap, and in late summer and fall, harvesting fruits and vegetables and canning them.

In comparison, in the factories where even the youngest workers put in twelve to fourteen hour days, mill work offered everyone and especially children a sharp contrast in daily routine from life on the farm. As a factory worker, the factory bell or whistle, not the sun, called you to work. Unlike farming, the steps in cotton production were set for you and you had to follow the directions of your supervisor. Your tasks were geared to the rhythm of the machine, not the rhythm of nature. You spent your whole day inside. You were expected to be punctual, self-disciplined, efficient and industrious.

One can see in the 1870 Massachusetts Census Report that girls were employed in the mills as weavers, frame tenders and frame spinners and both boys and girls were employed as spinners, warpers, and spoolers. The oldest children, sixteen year-old girls, worked as spinners and weavers; the youngest children aged ten and eleven, worked only as spinners. For instance, Elvira (eleven) and Frank (thirteen) Bates were both spinners, but Frank went to school. The French Canadian Bobier sisters, Delamor (ten, frame spinner), Adelaine (fourteen, frame spinner), and Liese (fifteen, weaver) did not attend school.

If you went to school in Coleraine, most likely you attended either a winter or a summer ten-week session with other students aged five to fifteen from your school district in a one room schoolhouse where a young, unmarried female teacher would teach you to read and write, and instruct you in arithmetic, geography, grammar, and U.S. history. Many of your lessons would emphasize good manners and the cultivation of personal virtues — honesty, industry, and patriotism. School was a social place where you met and played with friends, yet your family hoped school would provide you with the basic skills you would need for the new “modern” society and would encourage the values that would make you a responsible citizen.

This Saturday, June 7, come see Colraine’s third graders engage with this very history in their performance, with the Piti Theatre Company, of “Mill, Mountain, River: A Child’s View of Olde Coleraine” for Riverfest at the Senior Center ,7 Main Street, in Shelburne Falls, at 1:15pm.

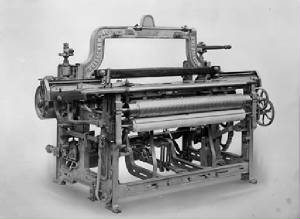

Photos, top to bottom:

Remnants of an old mill in Plainfield, MA; photo by Pleun Bouricius

Sample of an early 19th Century power loom; image courtesy of the Daily Dalton web site