As we enter the dimly lit room, adorned with family portraits and photographs, Orthodox icons glowing on walls, a frisson of mixed excitement and sadness engulfs me. Here, at hand, are fragments from a historical saga which has haunted my imagination since childhood. We have been wandering in an artistic wonderland at the Peabody Essex Museum’s “Fabergé Revealed” exhibit for nearly an hour when one work of art arrests the gaze and calls the heart with particular poignancy.

A historian cannot help but gaze with mixed emotions at the exquisite blue egg fashioned in shimmering gold and lapis lazuli. My eyes explore the tiny portrait of a seven-year-old boy, in a blue-and-white sailor suit. It is delicately painted on both sides of a piece of flat ivory, so that one will see the “complete” child, front and back, as one revolves around the case. He is nestled within the protective wings of a crowned, double-headed eagle, rising magnificently from the open, ancient symbol of rebirth.

* * * * *

A wooden hunting villa, Spala, Poland, 1912.

The child, delirious, had been screaming, moaning–and bleeding–for eleven days. A bumpy carriage ride in the forest had reopened wounds from an earlier injury. Blood seeped through torn vessels, filling his leg, groin, and abdomen with an enormous hematoma, causing his leg to draw up to his chest. All night, every day, his anguished parents heard his pleas and groans for God to have mercy on him; his exhausted and terrified mother, never undressing, scarcely left his side, not even to sleep.

Finally, it seemed clear that agony would end in death. Official announcements had to be drawn up, nationwide church services called for, prayers to begin the mourning process. All this was necessary, for the little hemophiliac sufferer was His Imperial Highness the Tsarevich Alexis, fifth child and only son of Nicholas II, Tsar of Russia, and his Empress, Alexandra Fedorovna. The dying child was heir to the throne of the 300-year Romanov dynasty, a dynastic line now drowning in blood.

Alexis, in extremis, received the last sacrament. The bulletin announcing the death of the Tsarevich was readied to be sent, news that would shock a grieving nation, which had not known of the child’s mysterious genetic illness.

In the depths of terror and despair, the Empress telegraphed a man in Siberia, a man who she believed talked with God. Her desperate plea for intercessory prayer was answered by telegram: “God has seen your tears and heard your prayers…. The Little One will not die. Do not allow the doctors to bother him too much.”

The next morning, the Empress was calm. She was sure “her” Father Gregory had spoken from a place of holy knowledge and vision.

A day later, the bleeding stopped.

The child would be crippled for most of the next year, but he lived. The following year the Romanovs would celebrate 300 years of rule. Alexis would be there through all the pageantry . . . sheltered from the lengthening shadows of the coming years.

Alexandra (“Sunny”) treasured the gorgeous blue-and-gold Faberge egg given to her later by her beloved Nicky. The jeweled Easter egg celebrated Alexis’ narrow escape from the grave. Its magnificence undoubtedly reflected for the devout parents, in some small measure, the magnificence of God’s mercy and the glory of prayers answered.

For such immortal work, only the creative vision of the jeweler Peter Karl Fabergé (1846-1920), and the supreme craftsmanship of his House of Faberge, would be worthy of commission.

Fabergé’s prominent position as jeweler to the Tsars began in 1882. Having won a gold medal at the Moscow Pan-Russian Industrial Exhibition, he attracted the attention of Nicholas’ father, Alexander III, Tsar of Russia (1881-1894).

Eventually, Fabergé was appointed Imperial Court Jeweler, an honor which assured and solidified his success for the duration of the dynasty. A devoted husband to his own Empress, Marie Fedorovna, in 1885 Alexander commissioned a white enamel egg to be given to his wife as an Easter gift. Fabergé designed an ingenious Imperial Hen Egg, which opened to show successive delightful surprises culminating in a hen wearing a diamond replica of the Imperial Crown.

Eventually, Fabergé was appointed Imperial Court Jeweler, an honor which assured and solidified his success for the duration of the dynasty. A devoted husband to his own Empress, Marie Fedorovna, in 1885 Alexander commissioned a white enamel egg to be given to his wife as an Easter gift. Fabergé designed an ingenious Imperial Hen Egg, which opened to show successive delightful surprises culminating in a hen wearing a diamond replica of the Imperial Crown.

Thereafter, Fabergé would be entrusted to deliver an Easter egg to the royal family, each year challenged to–and succeeding in–producing ever more intricate or inventive surprise creations. After Alexander died in 1894, his son gave an egg not only to his mother, but to his wife. Thereafter, the House of Fabergé produced many personalized eggs and other beautiful artistic creations for the family and for numerous formalized expressions of the Tsar’s favor.

The House of Fabergé would thrive and expand…until the shadows of war and revolution deepened into darkness, overtaking the Romanov dynasty, the Imperial Jeweler, and Russia herself.

See over 230 treasures of the House of Fabergé at The Peabody Essex Museum, in Salem, Massachusetts: “Fabergé Revealed” From the Collection of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Exhibit opened June 22, 2013 and will continue to Sept. 29, 2013.

Photos/Illustrations:

1) Imperial Tsesarevich Easter Egg (detail), 1912. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. Bequest of Lillian Thomas Pratt. Photo by Katherine Wetzel. © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

2) Imperial Column Portrait Frame, 1908. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. Bequest of Lillian Thomas Pratt. Photo by Katherine Wetzel. © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

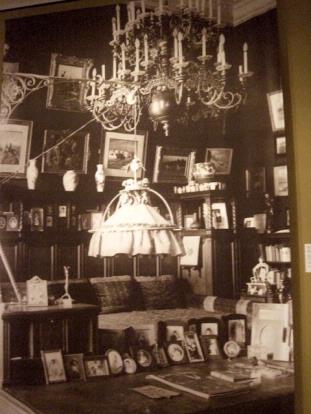

3) Nicholas and Alexandra, like most of their contemporaries, loved keepsakes and family portraits. The family was often photographed throughout their lives … even to the end days of captivity. Photo: Maggi Smith-Dalton; detail of a panel in the Peabody Essex Museum’s Faberge exhibit hall