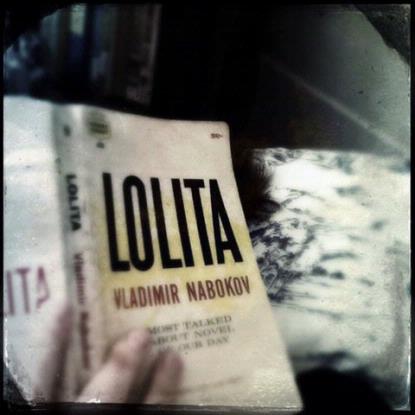

My husband is teaching a class called “Forbidden Fictions” this summer, to a self-selected group of high school almost-seniors. One of his first thoughts: “This might be the only opportunity I ever get to teach Lolita to high school students.”

He reread the book with far more discomfort this time around, for now he is the father of two 13-year-old girls. I noticed odd behavior when he took it out in public. He practically had to slip it inside a magazine or brown paper cover to read it in the waiting room of a doctor’s office. And the girls’ gymnastics gym, full of pre- and barely adolescent girls? No way. He sat in the car reading that night.

“Well, then,” I said, goading him as is my duty, “if it makes you this uncomfortable, why are you going to subject these poor young minds to it, traumatizing them forever?”

My sister supplied one answer as we stood around discussing the book over coffee on a sunny weekend morning. Wuthering Heights and Lolita were the first books she read, she said, that changed her “understanding of what literature is for or what is possible.” They expanded her ideas about “what might motivate me to read to something that goes beyond escape pleasure.”

(My other sister, telling me about a book she just read, said, “I haven’t loved a book so much since I read…Lolita!”)

My husband sent an email to a group of teacher and reader friends, asking for ideas about supplemental texts for the class, and one woman suggested he look at the 50 Shades of Grey phenomenon, how the book began online in an arena in which people often don’t censor themselves at all. The point is a good one—what does censorship, what does “forbidden” mean in a world in which we have direct access to the sordid contents of each other’s minds from the comfort of our homes? “But,” I howled in dismay, “you can’t teach 50 Shades—it’s not literature!” Maybe the subject matter is risqué—so what? If you enjoy redundant writing, and get a thrill following the jolly antics of a woman who screams “Holy cow!” whenever what’s-his-name tightens the handcuffs, then you go, girl, or boy, but I’m pretty sure this is reading for “escape pleasure.”

Does this sound snobbish? I don’t think so. Genre fiction can get us through hard times, and so can pop music, but we’re talking a literature class here, a bunch of bright kids preparing themselves for the rigors of college reading, not the reading they’ll do on the weekends to put all thoughts of their gimlet-eyed English teacher out of their minds. If they can crack Lolita, if they can extract even a portion of its juice, if they can broaden their understanding of what literature is for, they’ll be closer to ready—not just for college lit classes, but, as my sister says, “for the actual shades of grey that a full rich life must be lived in.”

Lolita starts with language so poetic, so unusual, that even once you know of what, and of whom, our unreliable narrator Humbert Humbert speaks, the words still dance around in your head like a refrain, still beg to be spoken, to spill from your tongue as the syllables of his beloved’s nickname slip from Humbert’s: “Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta.” Nabokov, in the voice of Humbert, seduces us with that language, draws us in, and in so doing makes us wonder if we are complicit in Humbert’s deeds. Our percolating discomfort lets us know his actions are wrong, wrong, wrong, but it’s hard not to feel sympathy for the devil. He’s pulled us inside his head. We feel his pain. Should we believe him? And the language is so gorgeous. We’re squirming not just in distaste, in revulsion at Humbert’s actions, but in delight, in awe at what that clever bastard Nabokov can do with language, at his power over words and through them his power over us. If we feel that thrill, that pressing desire to read on, then are we partly to blame for what happens?

If you want to be made even more uncomfortable, listen to Jeremy Irons read Lolita aloud, or read it when you have adolescent daughters—or, perhaps, read it in Tehran. But read it. Read it to understand how writing can be so powerful that people fear it, governments fear it, religions fear it. Read it to understand the possibilities inherent in literature, and to be grateful that, for the most part, we are free to read what we wish, from oft-banned books to forbidden fictions.