“What do women want?” Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, asked almost a century ago. On March 6, 1971, a group of women, many affiliated with the women’s liberation group Bread and Roses in Boston, Massachusetts, provided one answer. Celebrating International Women’s Day on the Boston Common, they issued their Declaration of Rights, “WE HOLD THESE TRUTHS TO BE SELF-EVIDENT: that all women and men are created equal and made unequal only by socialization….

On the Economy: We do not want merely to upgrade women into the alienated jobs that men now hold. We refuse to do the low grade, low paid and service work any more. Such jobs must be shared by men and women as must housework be shared.” The Declaration also demanded “control of our bodies,” free access to abortion, birth control and reproductive tests, and an end to drug testing on third world women, free community controlled twenty-four hour childcare, affordable housing, eliminating state interference in personal relationships, and “an end to advertising which exploits women’s bodies to sell products.”

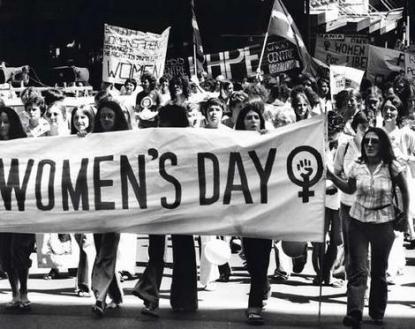

To dramatize their demands, the women marched past sites of women’s oppression in Boston, including the Playboy Club and the Charles Street Jail, then across the bridge into Cambridge. The surprise ending of the march was a building at 888 Memorial Drive, Cambridge, used by Harvard University for Design School classes and projects. The building takeover and occupation, its context and aftermath, is the subject of the documentary film “Left on Pearl: Women Take Over 888 Memorial Drive, Cambridge,” whose production has been funded in part by grants from Mass Humanities.

At a time when the media often pronounces “feminism” dead and valorizes “the new domesticity,” it is especially necessary to explore the issues that first ignited the women’s movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s, and to examine the impact of the movement known as Second Wave Feminism. Of the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s, the women’s movement is the least represented on film. Recent documentaries about the period, while highlighting the rich culture of protest that is part of the history of the U.S., are noteworthy for omitting mention of the women’s movement as part of the political milieu. Most young women today are unaware of the legal, educational and cultural barriers that restricted the lives of previous generations of women. In 1971, for example, classified employment ads were still listed according to gender; shelters for female victims of domestic violence did not exist, and abortion was illegal.

A chief purpose of women’s history remains making visible what is invisible or obscured in the shadows. Massachusetts, especially the Boston and Cambridge area, was one of the germinal centers of early Second Wave Feminism. In “Left on Pearl,” we focus on a unique action, one that involved feminists, community activists, and Harvard University, and received significant media attention at the time.

The 888 Women’s History Project was formed in 2002 in order to document the takeover. When we started, videos were recorded on tapes, and camcorders and playback equipment were bulky and expensive. We had little technical knowledge and soon realized that we needed someone with filmmaking expertise and experience to realize our vision. Susan Rivo, a local videographer, agreed to make the film, and has been working with us ever since, directing our project.

We have been fortunate not only to have found a talented filmmaker, but also in having excellent visual materials. These include a seventeen minute 8mm film of the demonstration, march, and takeover, and several hours of news footage from a Boston television station. In addition, we have interviewed many eyewitnesses and participants, who have provided us with varying perspectives on the takeover and its context.

The small group of women that secretly plotted the takeover chose a building located on a parcel of land which was already a flashpoint between the university and local residents. The working class, largely African American community in the immediate vicinity had been demanding that Harvard build low income housing on this very site to replace some of the vast housing stock that had been removed in the course of the university’s expansion.

Despite initial mutual suspicion, the women’s liberationists who were in the building and the Riverside neighborhood activists joined in supporting each other’s chief demands. The feminist occupation highlighted the need for a community women’s center and for affordable housing in Riverside. These issues are still relevant today, for many women and for the surrounding community.

In the ensuing days the occupied space itself became a sort of alternative liberated universe, full of excitement and experimentation, but in constant fear of police action and debate over strategy. Lesbians, still mostly closeted within both the women’s movement and the larger society, played a significant and visible leadership role in the building.

Want to learn the outcome of the takeover and its ongoing significance in Boston and beyond? Come to the fine cut screening of “Left on Pearl” on Sunday, March 6, 2011, the exact fortieth anniversary of the event, at 2PM, at the Brattle Theater, 40 Brattle Street, Cambridge.