When my family left China in 1948, I missed the movie theaters in Shanghai. On the boat to Hong Kong, my brother and I, in our early teens, vowed that we would sacrifice much to see Howard Hawks’ long-anticipated Red River. One year later, we saw it at an end-run cinema in Paris, dubbed in French. It was all that I expected, but waited to see it again with better comprehension.

That opportunity did not come up for three years. By then, I was in London and fifteen. It was “Saturday Morning Cowboy” in a distant, poor district, at a run-down picture-house. The hall was filled with shouting, plane-flying kids–a leftover print offered as relief for harassed parents. Regardless, I picked a front-row-center seat in the balcony– a habitual spot from Shanghai’s movie-palace days–used my palms as blinkers, and got transported to a revelatory experience.

What at thirteen, was a great adventure, at fifteen, told a different story:

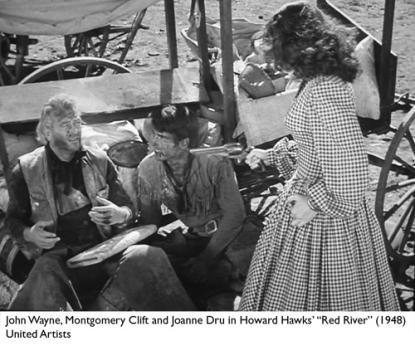

In the span of ten years, Tom Dunson (John Wayne) created a large cattle herd in Texas. In order to take it to market, he had to make an epic drive to Missouri. On the trail, out of fear and age, he became tyrannical. His son, Matthew (Montgomery Clift) interceded and took over to complete the drive. Dunson, feeling betrayed, swore to kill him. Meanwhile, Matthew met Tess (Joanne Dru), a woman in a wagon-train, and fell in love, but left to complete the mission. The expected shoot-out never happened. Tess, defusing the hurt and anger by invoking the love they had for each other, brought about a farcical end. At thirteen, I was disappointed, as were most critics of the period, castigating Hawks for introducing “sentiments” into a man’s movie. At fifteen, already skeptical of my earlier admiration for John Wayne’s swaggering ways, the alternative figures of Matthew, a man challenging authoritarian wrong-doings, and Tess, a woman instigating reconciliations, presented exemplary possibilities.

By 1952, after two years in Paris in a co-ed school by the Eiffel Tower, in a class of twelve with as many nationalities, I was at Shooter’s Hill Grammar School, at the outermost edge of London, with five-hundred-or-so school-uniformed boys. That same Shooter’s Hill was figured in the “best of times, worst of times” opening of Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities. My four years there, from fifteen to nineteen, were much of the Dickensian worst. I was the only foreigner among locals mostly geared to enter the labor-pool by mid-fifth-form (11th-grade). People were considerate. Early on, a Billy Graham devotee befriended me and offered salvation; I returned with the excitement of Gregory Peck’s forthcoming David and Bathsheba (a dud). Later, back from summer vacation in Paris, I tested rules by wearing rolled-up dungarees with the uniform blazer, but had to relent after three weeks, when I was called in to the Headmaster’s office with a cane conspicuously displayed behind him. I boarded with local families. I had no social life, and certainly no creditable adults around. My guide to life continued to be the movies. At fifteen, I no longer looked for heroic models, but ways to become a man, and with greater concern: what woman to love.

I played with puffed-chest and rolling-gait like Robert Mitchum, and practiced raising one eyebrow like Gregory Peck; but none of this was of much use: once the school-cap was on, it was still Tweedledum-Tweedledee. But looking inwards to my natural inclinations, I soon found easy affinity with the then-emerging marginal male characters. Finding a female image was more perplexing.

Hollywood in 1951 was hunkering down from Red-hunting blacklists; social questions were suppressed. New Hollywood’s representations of women seemed more-and-more limited to big-breasted blondes, scheming husband-hunters, or stand-by-your-man wives. All revolved around male exploits. For me, coming out of social circles fully expecting women to be society-changing activists, the offerings were stifling.

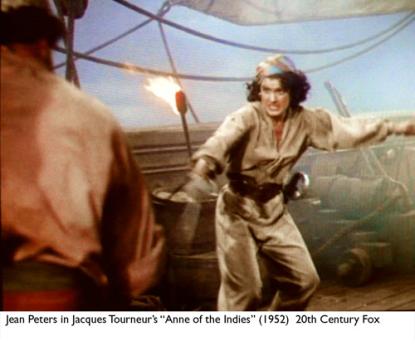

But, there were variations. One was Jean Peters in her early roles:

In Anne of the Indies (Jacques Tourneur, 1951), Capt. Providence (Jean Peters) an audacious buccaneer and skillful swordsman, captured a French privateer, LaRochelle (Louis Jourdan), and retained him as crew. He was, in fact, spying for the English to regain his captured ship and wife. Anne discovered love feelings despite herself. When his deceit was revealed, Anne, in pain, asserted her powers to have both LaRochelle and wife destroyed. But, relenting at the last moment (and conforming to Hollywood pattern) she provided them cover, and was herself killed. The character of Anne was very complex, reversing gender-roles multiple times, but she always retained control of the actions. By contrast, LaRochelle’s wife, though beautiful and well-gowned, was often cowering, tied up, and dispensed with. It touched deeply on the contradictions of the period.

Lure of the Wilderness (Jean Negulesco, 1952) also addressed the socialization of the woman. A young hunter, Ben (Jeffrey Hunter), chasing a dog, ran across an old man, falsely accused of murder, surviving with his daughter Laurie (Jean Peters) deep in the Okefenokee Swamp . The film offered two opposites: Laurie, a skilled hunter and knowledgeable in her environment, is forthright and intelligent; and Ben’s girlfriend in town is calculating and works her wiles deviously only to catch a man.

In the fall of 1955, Richard Burton and Claire Bloom, both coming out of successes in Hollywood, played Hamlet at the Old Vic, and a season of five Shakespeare plays in repertory. Hollywood had, by then, pretty much run dry for me: Rock Hudson/Doris Day war of the sexes had no appeal. My fealty was transferred to the theater. I started attending Old Vic almost every weekend. It got me through the last two years of Shooter’s Hill, and, then led to other things, and better times.

Early in1958, I sailed into New York Harbor on the HMS Queen Mary. The skyscraper skyline with steam and smoke resembled those in WWII newsreels, waterfront crime-dramas, and Cinemascope comedy/musicals, but, I was thinking mostly of Simone de Beauvoir’s descriptions of the same skyline in The Mandarins.

Soon, I would find another America: live jazz, the Beats, Joan Baez at Club 47, Franz Kline at MOMA… and, the marvels of going to the drive-ins, and, not-seeing the movie.