This piece is a continuation, of sorts, of an earlier article describing the process of the 100 Faces of War Experience project.

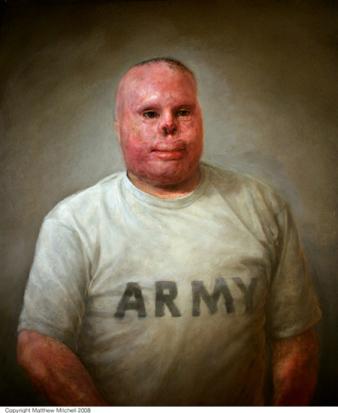

The particular thing I talk about here is the creation of the portrait of Rick Yarosh, an American soldier disfigured by burns, the acceptance of his portrait as part of the Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition and its display for one year the National Portrait Gallery, the media response to this event, Rick's response to this event, and the ongoing media attention.

It seems like the description of this process could be treated as an examination of how images become visible to wider audiences and how the cultural value of images is created.

First, a brief description of the project of which the portrait of Rick Yarosh is part. 100 Faces of War Experience is a series of 100 traditionally painted oil portraits of Americans who have gone to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. I meet each person who I represent in this project. When I do their portrait I ask them to provide some writing to accompany their portrait. Their statement can be anything they would like to say. The only criteria are that the statement be 250 words or less and that it be in some way different from all other statements in the project. Posthumous portraits are also included in the work, and for these portraits the families provide the statements for the person pictured. In this way I am seeking to create a broad and powerful understanding of the American experience of these wars. The project is a work in progress with 31 portraits and statements complete at this writing.

The story for the portrait of Rick Yarosh starts in May 2008. That is when I was given the chance to visit Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, TX .

On gaining permission to work at BAMC I immediately hopped on a plane and set out to do portraits of injured veterans. At that time I had only included one injured veteran and I knew it was necessary for the project to include more. Since 100 Faces is a visual project, or my part in it is visual, I knew I needed to find people whose injuries came across visually. Before my visit I had seen the photo of an injured Marine by Nina Berman, and another image of a man with facial burns photographed by Richard Avedon. These images are very powerful images and I thought I should seek someone who had suffered similar injuries. In my research I found that burns occur with some frequency in Iraq because they are an injury commonly associated with improvised explosive devises (IEDs).

My contact at BAMC was and is the Public Affairs Officer, Dewey Mitchell. Dewey has demonstrated to me time and again that he has very strong feelings about representing the injured veterans. Dewey quoted the English effort after the First World War to get their facially burned soldiers out into the public in order that they might better recover and that the public would get used to their disfigurement. Later I learned that the French adopted a similar policy called "Broken faces" where they featured facially injured veterans on stamps and widely in public places in order to try to normalize the experience of this kind of injury.

At BAMC I found that three people with burns were interested in having their portraits done. Representing three people injured by burns would not make much statistical sense (I aim to represent a broad range of wartime experience that has some basis in statistics), but I found it impossible to say no. I hope people will understand this. It seems to me it takes a rare kind of courage and trust for a burn survivor to have their portrait done. In San Antonio I also met three other wounded soldiers who volunteered to be part of the 100 Faces project.

I spent six days working with four people painting from life: two two-hour sessions with each of these four men. I interviewed the two others and I took photos from which to work later. It was an incredible six days, getting to know these remarkable people and painting their portraits.

BAMC is an unusual environment. Injury is normalized there. As I painted in the Fischer house for injured veterans and their families I listened to a group of young men in the living room talk about prosthetic legs: the different ways of putting them on, the different kinds that were becoming available. It seemed like a positive and exceptional community in which to live with injuries. It seemed to me that this is what a community looks like in which injury is normal and accepted.

I also found this social environment comfortable and accepting of my work as an artist. As an artist you have the opportunity to see beauty in all places. When each of the people with visible injuries first entered the room I was somewhat shocked. It is hard not to be shocked when you look into the faces of burn victims and see that they don't have many features.

However, when you start to paint, you see the beauty. It is possible to see beauty in all things. Each of these men, when considered openly, without preconceptions, has a remarkable appearance that has a great deal of inherent beauty. I find I grow a real respect and fascination with everyone's appearance whom I paint.

The experience in San Antonio was a week in my life that I will never forget.

When I returned home I experienced a kind of return to "reality" that surprised me. When my wife picked me at the airport, I told her about how incredible the trip had been and about these incredible people I had met.

In the living room at home I unpacked the boxes and stood the paintings up around the room. I invited my wife in, fairly proudly. She came in, looked at the paintings and said, "I think I have to sit down." I truly was not expecting this reaction. I had been in a different world. In the back of my mind I knew that these paintings would be shocking to some people, but I had started to believe there was some hope they would not be shocking. I had been granted the privilege of seeing through the injuries of the people I had worked with and I expected, or hoped, that other people would be able to do this too.

Since that time Rebecca and some other viewers of the paintings have told me the paintings have worked this way for them. Rick's portrait and the other injured veterans have become more full personalities rather than depictions of injuries. The injuries are there, and always will be, and there will always be hardship associated with these injuries, but there is something else that is strong in the images as well.

When I continued to work on the portraits from photos in the studio Rick Yarosh's portrait and Nick McCoy's portrait came together easily. I was able also to work on Dale Morgan's portrait and finish it.

Suddenly, with the end of July, came the deadline for submissions to the Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition.

At that time I had 26 portraits complete in the 100 Faces project. The Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition held the opportunity to bring the 100 Faces project to national attention. Additionally, the first prize in the competition was $25,000. I had been working on the 100 Faces project for three years at that point, going into personal debt, and I had reached the end of my credit capacity. The prize for the national recognition could be an important part of being able to continue the work. Thirty-three hundred portraits would be submitted to this competition, less than fifty would be selected as finalists.

I could only choose one portrait to submit. I chose the portrait of Rick Yarosh. The decision was based on several things. The most important thing was that Rick loved the portrait and was very vocal about his appreciation of it. I also thought/hoped that people really could look at this work and see through the injuries. The work also has an iconic look. Rick had chosen to wear a shirt that said “Army.” This shirt combined with his facial burns, his look of pride, and his words that accompanied the portrait conveyed a complex and provocative narrative.

I could only choose one portrait to submit. I chose the portrait of Rick Yarosh. The decision was based on several things. The most important thing was that Rick loved the portrait and was very vocal about his appreciation of it. I also thought/hoped that people really could look at this work and see through the injuries. The work also has an iconic look. Rick had chosen to wear a shirt that said “Army.” This shirt combined with his facial burns, his look of pride, and his words that accompanied the portrait conveyed a complex and provocative narrative.

It made me uneasy to separate one portrait from the group. The whole point of the 100 Faces project is to show multiple perspectives. I did what I could to address this issue by requesting that a plaque accompany the painting explaining that Rick's portrait and statement were part of a larger work.

Ten months later, in June 2009, I received word that the portrait of Rick Yarosh had indeed been selected as a finalist in the OBPC and would be exhibited in the National Portrait Gallery as part of that competition from October 2009 to August 2010. Also with this news came the announcement that I had not been put on the short list and would not be receiving any of the cash prizes. I invited Rick to the opening reception, to be held in October, 2009.

In September, I talked with Dewey Mitchell at BAMC. Since visiting BAMC, I had been trying to get the 100 Faces exhibition to be exhibited in San Antonio. I had made no progress, it takes some doing to ship the art across the country and no one had decided they could foot the bill. Dewey seemed disappointed. He had expressed several times a desire to see the 100 Faces project exhibited in his area so the injured veterans could see the final paintings in person and get the full feeling of the exhibition. He expressed several times his belief that the injured veterans benefit from being part of projects like this.

Around this time an Associated Press reporter contacted me. Michelle Roberts had heard Dewey mention the 100 Faces project and had started asking questions about it. Michelle Roberts wrote an article on the 100 Faces project and it started circulation on the AP wire shortly before the opening reception for the portrait competition.

At about this time I sent an inquiry to CBS about the project and they had started filming a news segment about the work.

By the time of the opening at the National Portrait Gallery the press was thoroughly interested. Rick and I each spent the majority of the time at the opening being interviewed and filmed. CBS, AOL/Time (their coverage is here), the Washington Post (see their article here), and Agence France Press all interviewed us. Rick aptly handled all the probing questions, and I think it is pretty safe to say most of the media there were more interested in talking with Rick than in talking with me. The interesting part of the portrait for them and perhaps for the jury that judged the Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition, is the way that Rick participated in the process by offering his story to go with the portrait.

I suspect this aspect was important to the jury of the competition because, the day after the opening, I received an email from a fellow artist named Doug Auld. He asked if I was aware of his work painting portraits of burn survivors. Over the course of our correspondence he revealed he had had one of his burn survivor portraits included in the last Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition in 2006. He also revealed that he entered the competition again this time and that his entry was a portrait of J.R. Martinez, an Iraq veteran disfigured by burns. The entry was not accepted.

One way of looking at these events is that the appearance of a person like Rick has an incredible value. When he allowed me to do his portrait, when he provided his words to go with that portrait, and in all his enthusiasm since then, he has made a major endorsement of the 100 Faces project. With his endorsement he has also had to endure a lot of probing questions by the media. The questions are not always the kind of questions you would ask a friend. Some seem intended to evoke a reaction of pain.

However, Rick has embraced the role of working publicly. He has worked in the past as an inspirational speaker and intends to continue to do this work, he seems pretty comfortable with this public role. My respect for him has grown considerably and I am happy that we are bound to keep in touch because of the way the painting has become a bond between us. His belief in the work has done more to bring the work to the public than anything else.

With the media there have also been, predictably, a lot of misunderstandings of the nature of the project. It seems no one can actually believe that the people in the project are allowed to say whatever they want to say. It is hard to drive home the point that we are striving for multiple perspectives. So, with the media, there is a good amount of time spent answering emails which misunderstand the nature of the work.

Once again the point is brought home how the paintings I do are just part of the puzzle. The portraits become a kind of currency within a much larger social exchange of ideas.