Whither Digital Natives?

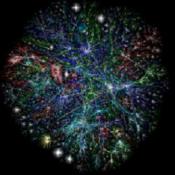

Rumor has it that the nature of human thinking is changing. As Nicholas Carr puts it in Is Google Making Us Stupid? What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains, "Over the past few years I’ve had an uncomfortable sense that someone, or something, has been tinkering with my brain, remapping the neural circuitry, reprogramming the memory." An unsettling idea, and yet, it does make sense. The human brain is fairly plastic, after all, reacting constantly to its environment, creating neural pathways as necessary to process stimuli. The brain has apparently been tweaking itself throughout human history; the hoe, the wheel, the clock, the book, the assembly line, television have all (in conjunction with the physical activity they require and the social adaptations they generate) changed the ways we interact with our environment, probably rewiring our brains in the process. Marc Prensky is convinced that young people are beginning to think differently, and anecdotal evidence suggests that all of us are adjusting in ways large, small, exhilarating and daunting, to changes wrought by the Internet and related tools. The question on my mind is whether young people have any need during this sea change for the guidance of their elders.

Rumor has it that the nature of human thinking is changing. As Nicholas Carr puts it in Is Google Making Us Stupid? What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains, "Over the past few years I’ve had an uncomfortable sense that someone, or something, has been tinkering with my brain, remapping the neural circuitry, reprogramming the memory." An unsettling idea, and yet, it does make sense. The human brain is fairly plastic, after all, reacting constantly to its environment, creating neural pathways as necessary to process stimuli. The brain has apparently been tweaking itself throughout human history; the hoe, the wheel, the clock, the book, the assembly line, television have all (in conjunction with the physical activity they require and the social adaptations they generate) changed the ways we interact with our environment, probably rewiring our brains in the process. Marc Prensky is convinced that young people are beginning to think differently, and anecdotal evidence suggests that all of us are adjusting in ways large, small, exhilarating and daunting, to changes wrought by the Internet and related tools. The question on my mind is whether young people have any need during this sea change for the guidance of their elders.

Let’s assume for the purposes of this post that current technology is indeed changing our ways of accessing and processing information. Let’s also accept Prensky’s broad division of people into "digital immigrants" who were born before the advent of the Internet, and "digital natives" who know only a wired, always-connected world. We have probably all observed that digital immigrants can be quick to throw up their hands and abandon the field to the native young, who are considered uniquely qualified to cope with the new technologies and the social changes they spawn. They–and by that I mean "we"– may bewail the new order, but we accept as given that "our" world is passing away and "their" world is taking over. This is not so different from the situation of real world immigrants and their native-born children. The adult generation often responds to language and competency challenges by withdrawing from the fray, leaving the young folks on their own to navigate the new world.

But what might happen if we immigrants refuse to recede into the background, and instead summon the courage to stay engaged, to discern which values from the old world need to be integrated into the new world, and resist being intimidated by the new culture, even though we have funny accents, feel awkward, and stumble around a lot? The more I observe this remarkable period of change we’re living through, the more I believe that younger people badly need the older generation’s help in making sense of the mind-boggling technical tools and possibilities that are their unavoidable future.

summon the courage to stay engaged, to discern which values from the old world need to be integrated into the new world, and resist being intimidated by the new culture, even though we have funny accents, feel awkward, and stumble around a lot? The more I observe this remarkable period of change we’re living through, the more I believe that younger people badly need the older generation’s help in making sense of the mind-boggling technical tools and possibilities that are their unavoidable future.

Digital natives know how to push buttons; they are fearless in the face of new gadgets, and they can type very fast with their thumbs. But recent reports indicate that their information literacy has not improved with greater access to technology, and that young people have "unsophisticated mental maps of what the internet is, often failing to appreciate that it is a collection of networked resources from different providers." (p 12) They generally do not know how to access the "deep web" beyond Google, are unaware that peer-reviewed literature offers a way out of the morass of opinion masquerading as fact on the Web, and they are frighteningly unskilled in knowing how to evaluate the validity of an information source.

A 4th grade teacher I know says despairingly that the majority of her students believe that the Apollo moon landing was faked because they "read it on the Internet," yet the curriculum she is tied to allows scant time for teaching them how to distinguish fact from loony, but footnoted, fiction. Schools are making sure that students can fill in the bubbles on standardized tests, hoping they will get more answers "right" than "wrong." If they were not withdrawn from reality, schools would be ensuring, instead, that students knew how to collaborate in international project teams, could convey a clear message in 140 characters or less, were able to assess a Wikipedia article and edit it online if it failed to meet academic standards, could effectively skim text for content, and could efficiently use handheld devices for mapping, communications and multimedia projects rather than having their cell phones banned in the classroom.

Digital immigrants have a wide range of vital skills to convey to their younger colleagues and offspring, from the tenets of civil discourse and the fundamentals of critical thinking, to the ability to assess the relevance, accuracy and authority of source data. If young people are going to thrive in a world that is still quite unimaginable to all of us, then they will need to be highly creative, able to rapidly master new tools while dealing effectively with a limitless flow of information through skilled collaboration with others across space and time. As things stand, they are pretty much educating themselves in these areas, with predictably limited results. Despite their energy and creative potential and willingness to forge ahead into the future, young people are not prepared for the new world. They need the rest of us to jump in, remain engaged, learn what we can, teach what we know, and contribute as much as possible of our world’s wisdom and its "best practices" to their efforts.