On the web, history, like everything else, is a participatory activity. It’s not about visiting an online exhibit, it’s about engaging in an ongoing conversation. What do you see? Who is in this picture? Where and when was it taken? What is the story here? And what does it really mean?

Many photographs come to libraries, museums and archives with limited information. Of course, these institutions could enhance their collections by hiring professionals to carefully research each image, but that’s an expensive solution, and some information can’t be found in traditional sources. The Library of Congress is experimenting with a different approach : crowdsourcing, or inviting participation from anyone interested. They have taken over three thousand photographs for which they had minimal information, and posted them on the popular photosharing site, Flickr, inviting members to comment freely, to help organize the collection by adding tags, and to freely use these public domain works. The results have been impressive. Many of the pictures have been viewed hundreds or even thousands of times, with lots of comments from the crowd, often adding significantly to the identification and understanding of the image.

For example, one photograph by Jack Delano was originally identified just as “Street in industrial town in Massachusetts.”

Flickr members quickly provided an exact location for the picture of Sylvia Sweet’s Tea Room, located at the corner of Main and School Streets in Brockton, and narrowed the date based on the movie poster in a window.

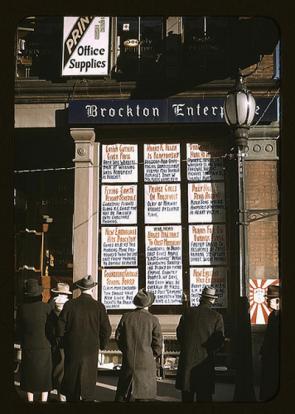

Another Brockton photograph shows the newspaper office, with headlines posted in the window.

Flickr members were able to decipher those news postings, do a little research, and determine that the picture had to have been taken on December 24, 1940. Some members add links to other sources of information, often to the PDF version of New York Times articles, available online free at the newspaper’s site from 1851 to 1922. For example, a photograph of a distinguished group of men was originally just identified as “German Doctors at Ellis Isl. [between 1910 and 1915].” Flickr member Brooke Stewart posted the information that the doctors were in New York to attend the 1912 Congress on Hygiene and Demography, and added a link to a New York Times account of their stay at the Plaza, with the headline “"German Doctors Try Turkey Trot; And One of the Distinguished Visitors Is Now Mourning a Vanished Tooth."

The Library of Congress isn’t the only library with historic photographs on Flickr. The Boston Public Library also has a Flickr account with over six thousand images, including over 1,800 beautiful Tichnor Brothers postcards of Massachusetts.

Flickr members also participate in history groups, sharing their own family photographs and other old photographs, as well as current pictures of historic locations, endangered buildings, artifacts of all kinds, and other sites and events that are or will be of historic interest.

In one group, The Great Postcard Hunt, Flickr members take current pictures to match historic postcards, and digitally splice the two images together. There are other groups devoted to every period and aspect of history, from the Ancient Near East to the Rock ‘n’ Roll Historic Sites. You can find many of Flickr’s history groups listed in the History Directory group.

Shorpy is another popular site for the those who love historic photographs. Calling itself “the 100-year-old photography blog that brings our ancestors back, at least to the desktop,” Shorpy posts a few selected images every day, often by noted documentary photographers Lewis Hine, Jack Delano, Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams and others. The blog format works well for this site, highlighting a steady stream of fascinating photographs to a devoted community of users who follow the site regularly and participate in discussion about the photographs. Some of the Shorpy photographs get hundreds or even thousands of views.

Shorpy was named after Shorpy Higginbotham, a child laboror in a mine in Alabama, photographed by Lewis Hine, whose work is well-represented on this site. A recently-posted Hine photograph is simply captioned, "Arthur Chalifoux, 3 Rand St. (4th boy from left). Works in Eclipse Mills, No. Adams. Location: North Adams, Massachusetts, 1911." Joe Manning posted more information on this photograph. As part of his Lewis Hine Project , Manning tracked down the grandson of Arthur Chalifoux, who lived to be 92 years old. The family was unaware that this photograph existed, and had never seen a boyhood photograph of Chalifoux. Manning has researched the stories of many of Lewis Hine’s subjects, and located the descendants of many of them.

There are also many people who are combining history with geography, and putting their historic images on interactive maps. For example, the Waymarking site has a group called Historic Markers of Massachusetts . Each marker is geocoded to put it on the map, photographed, transcribed and described, creating a unique and useful guide to historic sites in the state. LuciaM, Master Guide, created a Google Earth file called Phillis Wheatley: Slave, Poet, American which provides an interactive tour of places of significance in Wheatley’s life and work, combining geographical and biographical information and literary works into an engaging presentation.

Schools and other educational and cultural organizations are also producing and sharing all sorts of history material on the web. “Our Neighborhood: South Worcester” is a short film produced as a a collaboration of WCCA TV 13, the South Worcester Neighborhood Center, and the Worcester Public Schools, and follows the activities of a group of students from the Canterbury Street School as they explore the culture and history of their neighborhood. This film was contributed to the Open Source Movies collection of the Internet Archive for preservation and distribution.

We’re living through a period of great social, political and economic change. But as we move forward, many of us feel a deep need to look back at our personal and collective histories to see we’ve been, and understand where we’re going. Network technology provides individuals and groups ways to share and collaborate on a scale we could hardly have imagined twenty years ago, and will continue to change the way we study and explore history.