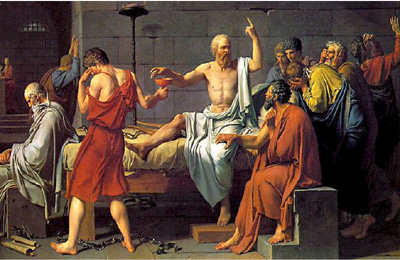

Here in America, we are, at least to all appearances, spoiled for choice in the wide, well-stocked aisles of our daily lives as consumers. Cars and computers, colleges and health clubs spread out across the open price range, each promising to be “worth it”. In our political lives as citizens, however, we have fewer choices. In fact, we may have only two at the end of the day, when the buzz and frenzy are exhausted and we are left alone with our thoughts. Such was the conviction of Socrates in his cell—his friends gathered round—awaiting execution for telling the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. Although he was the only one about to die, Socrates was fearless, while his friends, at no personal risk, were hopeless. Socrates had made one choice and they another.

Whether we find ourselves in a prison cell or a polling place, our choices do seem to come down to these two: fear or hope. Throughout the history of Western political philosophy—from Plato’s Republic to Machiavelli’s Prince to Hobbes’s Leviathon to the Bush Doctrine—we are presented with the same option: whether to live from fear or to live from hope. I have used “hope” here to stand in for classical “desire” or “love” (eros) which is unlikely to be understood by us as it was earlier meant; for its proper and ultimate object was for centuries understood as the best good, the summum bonum, on which our ultra-modern or, what’s worse, postmodern minds are all too likely to fall blank. Desire, for us, is mostly private and selfish, something we keep to and for ourselves.

The highest good was once understood as a common good, a telos or final aspiration that, unlike oil, is only enhanced, never diminished, as it is shared. That there is such a good, that its pursuit is our shared responsibility, and that its enjoyment is our ultimate purpose—these are elusive and hard sayings for us today. After all, we are all but convinced that there is no singular good, only goods, goods that divide us, pit us against one another, bring us to blows. These consumer goods are limited and we consumers are not, neither in number nor in hunger. A world in which countless, covetous individuals and individual states are all after the same few things as if their lives and happiness depended on them—that is indeed a dangerous world in which fear would appear the most reasonable and inevitable posture.

Socrates and Plato, speaking with one voice, noted that we have only two basic passions: fear and desire. Desire, as they understood it, lifts us up and brings us together, for its only true object is either infinitely shareable or nothing at all. In other words, desire is the longing affirmation of things imagined but as yet unseen. We call this hope. Fear, on the other hand, knows its object all too intimately—death. Death, of course, assumes many shapes and moves at many speeds; but it is always a matter of diminishment and denial, ending in nothingness. This is the summum malum, the worst evil—violent, unforeseen death at the hands of another, at least as Hobbes witnessed and described it. Summum bonum vs. summum malum, love and affirmation vs. fear and suspicion—these are our choices, outlined and espoused across the centuries and currently on the campaign trail. We can either live in accord with what is highest in us, or navigate by what is lowest in us. Naturally we want it both ways, the sweet frozen swirl. Like Machiavelli’s Prince, we want both to love and to fear, to be both loved and feared; but, wants aside, he was clear on this even if we are not: we have to choose, set our priorities, decide what is real and what only pretence. Machiavelli chose to ridicule the highest good, to scorn hope as sheer illusion, and to propose that we “adopt the beast” as our tutor. There are armed prophets and unarmed prophets, he pointed out; and the armed prophets always win, while the unarmed prophets always lose. Armed force decides everything. War is our natural state. We must either be at war or hard at practice in the ways of war at all times. The rest is folly and illusion. If we manage to be loved for a while, all the better; but what is essential is to be feared. Old words, old advice, recycled in the media as the latest common sense. Imagine a telephone ringing at 3am and you get the point.

Returning to the deathbed of Socrates, we find the hemlocked philosopher encircled by his closest friends who are all but collapsing in grief and fear. His advice is to consider for a moment how what is nearest at hand always appears greatest. Move your thumb closer and closer to your eye and it will soon seem larger than a mountain, the sky, or the entire world. Move it away and it gets smaller and eventually becomes a mere thumb again. Whatever is pressed against our mind’s eye seems the greatest, most urgent, most real matter there is, demanding our attention to the exclusion of all else. This is the way that fear and its politics captivate a nation and lead them to the low road and to ruin. Whether we dial 9-1-1 or 911 we connect to our worst fears. The alternative is to give our fears a rest and to aspire to be more than an object of fear to others. We might even listen in a spirit of hope to the words of Albert Camus and wonder what he meant when he wrote that the greatest gift to history and to the future is generosity to the present.

–Bob Meagher is Professor of Humanities at Hampshire College.