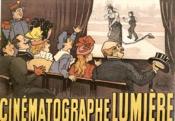

The history of moving images is remarkably short compared to that of writing, painting and music making. The first public screening of moving images took place in Paris on December 28, 1895, not much more than a hundred years ago. The show consisted of a series of silent, fifty second scenes of, among other things, a train arriving at a station, a wave breaking, children engaged in a snowball fight, and workers exiting the Lumiere family camera manufacturing facility. The images were recorded by a remarkable device invented by two brothers, August and Louis Lumiere, whose father owned a factory that manufactured still cameras. The same box-like instrument exposed images on film, then served as chemical developing tank and projector as well.

The history of moving images is remarkably short compared to that of writing, painting and music making. The first public screening of moving images took place in Paris on December 28, 1895, not much more than a hundred years ago. The show consisted of a series of silent, fifty second scenes of, among other things, a train arriving at a station, a wave breaking, children engaged in a snowball fight, and workers exiting the Lumiere family camera manufacturing facility. The images were recorded by a remarkable device invented by two brothers, August and Louis Lumiere, whose father owned a factory that manufactured still cameras. The same box-like instrument exposed images on film, then served as chemical developing tank and projector as well.

The show was a great success, and ran for more than a year to packed houses. It was glowingly reviewed in Paris newspapers the day following the premiere, and one reviewer in particular made a remarkable statement: “From now on,” he wrote, “there is no death.” Since photography in one form or another had been around for some sixty years previously, it was evidently not the image itself, but the movement that was transformational.

There was, of course, no movement. What flabbergasted early viewers (Maxim Gorky, reviewing a Lumiere road show in Moscow the following year noted that some patrons in the front row had risen from their seats and fled when the wave broke) actually saw was a series of still photographs passing in front of a light in quick succession interrupted at numerous times per second by darkness caused by a three-bladed rotating shutter.

There was, of course, no movement. What flabbergasted early viewers (Maxim Gorky, reviewing a Lumiere road show in Moscow the following year noted that some patrons in the front row had risen from their seats and fled when the wave broke) actually saw was a series of still photographs passing in front of a light in quick succession interrupted at numerous times per second by darkness caused by a three-bladed rotating shutter.

The phenomenon which made this illusion possible, more remarkably still, was an error in human perception: the inability of the brain, in conjunction with the eye, to rid itself of one image before it is replaced by one slightly different. This error is known as the persistence of vision and is the basis for the persuasiveness of all moving image technologies.

But this ‘movement’ was indeed transformational. Seeing an image of someone appearing to breathe and move is entirely different from seeing a still image, typically representing a frozen fiftieth of a second, something utterly unrealistic by comparison.

Coupled with the development of shooting and editing techniques, the new technology was poised to succeed brilliantly. Still, if almost everyone was dazzled by the fact of movies, not all of them were persuaded by the value of the new technology. It is a melancholy fact that education by definition involves studying – the past. So it was that the most educated audiences for the new technology were steeped in the conventions of its predecessor — the theatre. To many of them, the conventions of film as they developed were disturbing. When you went to the theatre, you “saw” the stage from a fixed point of view – your seat. A film, however, might feature a close-up of a face that took up the entire height of an eight foot high screen, followed by a wide shot in which that same face might be only inches high, a monstrous juxtaposition to someone accustomed to the theatre.

And so the audiences that most enthusiastically responded to the “movies” tended to be less educated: people with less to unlearn, as it were. But even among them, the power of film was often misattributed. This was brilliantly shown in a series of exercises developed by one of the most brilliant of early film teachers, the Russian Lev Kuleshov in 1917.

Kuleshov took one of the leading men of the nascent Russian cinema, a handsome young Armenian named Musjakian, and shot a close-up of him looking neutrally at the camera for a couple of minutes. He then inter-cut this shot with a close-up of a bowl of steaming hot soup, then with a close-up of a dead child, and finally with a shot of a woman exiting a train, then running toward the camera with an ecstatic expression on her face. When he and his students showed the sequence to workers at a Leningrad factory after a shift change, most members of the audience were amazed by the power of — Musjakian’s acting! How in the first scene, he was striving to look indifferent but was plainly starving to death; in the second, he was trying in suppress his emotion but was plainly devastated by the death of – his son. And in the third, though again striving to be restrained and manly, he was clearly overjoyed at the sight of — his mistress.

Kuleshov followed that up by another exercise, in which he filmed a young woman getting dressed entirely in close-up – her hands pulling on stockings, her arms pulling a shift over her head, etc. At the end of the class in which he showed the sequence, one of his students begged him for the address of the young woman, by whom he was clearly smitten. Kuleshov gravely refused, despite the student’s assurances of his good intentions. Finally, after being further pressed, Kuleshov confessed that the young woman with whom the student was infatuated consisted in fact of four different women, and one man.

So you see, Kuleshov concluded, I have created an entirely fictional creature that is nonetheless capable of inspiring passion. The central creative heart of filmmaking, he concluded, was editing which, along with the multiple points of view enabled by camera position, enabled film to far surpass theatre in expressive range and power.

How true this was is attested to by the fact that, as early as 1920, both Pope Benedict XV and Vladimir Illyich Lenin, who agreed on little else, both pronounced film to be the most influential art form in the history of the world.

But in a further paradox, the foremost innovator in the history of American cinema was a man of the theatre – D.W. Griffith. And he used the new technology – which like all technologies is amoral — to promote a virulently racist ideology. His most powerful film, the founding ‘masterpiece’ of American cinema, Birth of a Nation, is one of the most morally disgusting films ever made, the widespread exhibition of which is arguably responsible for the murder of hundreds of African American citizens at the hands of a rejuvenated Klu Klux Klan, which brings us back to our starting point: Ms. Simmons charge of racism in American filmmaking.

That film is a medium of phenomenal power is undeniable. That there is racism in American filmmaking is also, I think, undeniable. I would assert as well, without offering evidence, that it is less virulent now than it was at the beginning. But whether it is a cause or merely a symptom is very much subject to continuing debate. If films are merely symptoms of the zeitgeist of the times, Ms. Simmon’s injunction to produce different kinds of films is likely to have less effect, even if carried out, than if films can in fact cause different values to be instilled. I hope to engage that subject in a later post.

–Tim Wright, Documentary Filmmaker